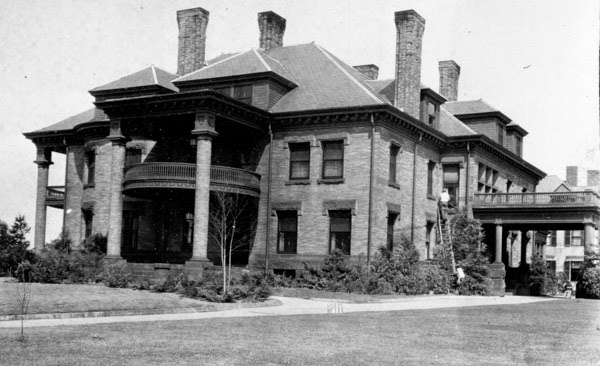

The house at 220 Maple Street in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The house in 2017:

Since the 1880s, Springfield has been known as the “City of Homes,” and features hundreds of historic late 19th and early 20th century houses with a variety of architectural styles. Despite this, though, very few of these were designed by nationally-recognized architects. One of the exceptions was this house on Maple Street, which was designed by the Boston firm of Ware & Van Brunt. Their works were primarily Gothic in style, and the two men had previously designed Harvard’s Memorial Hall, which is considered one of the finest examples of High Victorian Gothic architecture in the country.

While Memorial Hall was still under construction in Cambridge, Ware & Van Brunt was hired by Frances Loomis to design a house for her on Maple Street, near the top of the hill that overlooks downtown Springfield and the Connecticut River. The actual construction was done by Chauncey Shepard, an architect and builder who, nearly a half century earlier, had designed and built the nearby David Ames, Jr. House. Shepard built the Loomis house from 1873 to 1874, and he died the following year, at the age of 78.

Frances Loomis was the widow of Calvin Loomis, a cigar manufacturer who had moved from Vermont to Springfield in 1853 and opened a business along with W.H. Wright, who later took over the company. Calvin Loomis died in 1866, and Frances died in 1877, just three years after moving into this house. The house was subsequently owned by Frank L. Wesson, the son of Smith & Wesson co-founder Daniel B. Wesson. He lived here with his wife Sarah and their children, but he was killed in a railroad accident in Hartford, Vermont on February 5, 1887. He was 34 at the time, and was one of about 37 people who were killed when his train stuck a broken rail and fell off a bridge over the White River.

The house remained in the Wesson family for many years, although it does not appear to have been occupied in either the 1900 or 1910 censuses. By 1920, though, it was the home of Frank’s oldest son Harold, who was living here with his wife Helen along with a servant. The couple’s only child, also named Helen, was born in 1908, but died when she was just three days old. Harold eventually became the president of Smith & Wesson, and was still living here in 1930, although by the 1940 census he and Helen had moved to Longmeadow.

The house appears to have been vacant again in 1940, but was later owned by Joseph Loeffler, who added the two-car garage to the front of the house in 1946. Otherwise, the exterior has seen few changes. Like most of the neighboring homes, it sustained heavy damage from the June 1, 2011 tornado, but it was restored. It is an excellent surviving example of the city’s grand 19th century mansions, and is part of the Ames/Crescent Hill Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places.