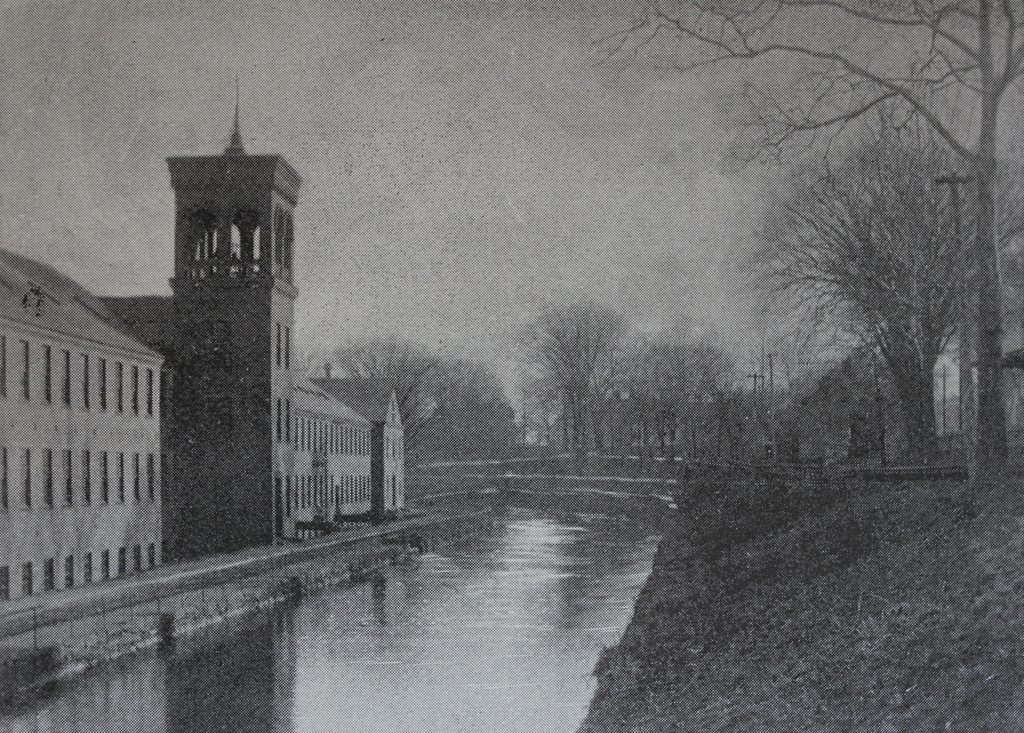

The Ames Manufacturing Company on Springfield Street in Chicopee, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

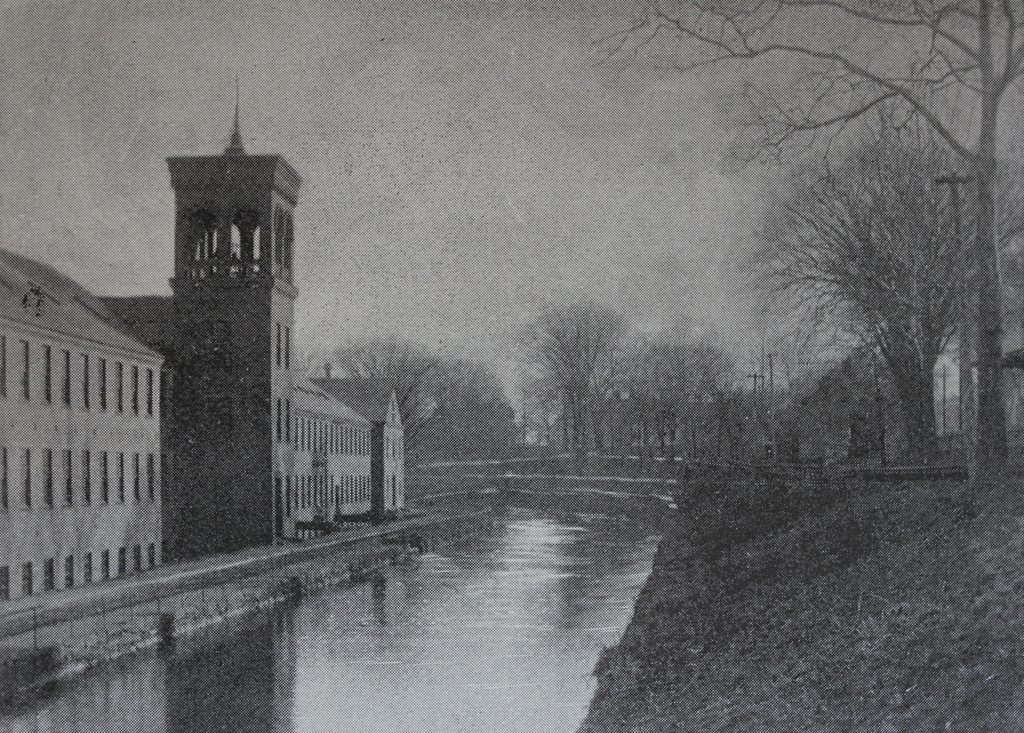

The scene in 2017:

The origins of the Ames Manufacturing Company date back to 1822, when industrialist Edmund Dwight purchased property along the Chicopee River at Skenungonuck Falls, at the present-day village of Chicopee Falls. At the time, Chicopee was the sparsely-settled northern half of Springfield, but the Industrial Revolution helped to transform it into a major manufacturing center, thanks to the many waterfalls here on the Chicopee River. In 1823, Dwight incorporated the Boston and Springfield Manufacturing Company, and within a few years he had built a dam, a canal, and a mill at Chicopee Falls, marking the beginning of large-scale industry here in Chicopee.

In 1829, Dwight persuaded brothers Nathan P. and James T. Ames to relocate their cutlery business from Chelmsford to Chicopee Falls. He provided them with a blacksmith shop at his mill complex, rent-free for four years, and the brothers began operations here with a workforce of nine. The business rapidly expanded, though, and by 1833 they had 25 to 30 employees and were producing a wide variety of cutlery and tools, as well as swords for the Army and Navy.

The company was incorporated as the Ames Manufacturing Company in 1834, and the following year moved to this site further down the river. Known at the time as Cabotville, this village would later become the center of Chicopee when it was incorporated as a separate town in 1848. Here, the Chicopee River drops 50 feet in elevation, and both a dam and a canal were constructed in the early 1830s. At this new site, the company continued to grow and diversify, and by the end of the 1830s the Ames brothers were also producing cannons, cannonballs, bells, and a variety of other metal objects.

The first photo, taken in the early 1890s, shows the canal in the center and the Ames complex on the left. These buildings were constructed starting in 1847, with the oldest section visible just to the right of the tower. The facility was steadily expanded in the following decades, and was largely in its present form by the end of the Civil War. This era marked the heyday of Ames Manufacturing, which produced munitions during both the Mexican War and the Civil War. The Civil War in particular brought prosperity, and this facility became one of the war’s leading producers of swords, light artillery, and heavy ordnance.

During this period, the company also began casting bronze statues, beginning in 1853. Under the direction of foundry superintendent Silas Mosman, Jr., the company produced many important statues, including the Benjamin Franklin statue at Boston’s Old City Hall, the equestrian statues of George Washington at the Boston Public Garden and New York’s Union Square, the Minuteman statue at Concord, and the statues at Abraham Lincoln’s tomb in Springfield, Illinois. However, perhaps Mosman’s most significant accomplishment was casting the bronze doors for the east wing of the U.S. Capitol, which were installed in 1867. In his later years, Silas Mosman was assisted in his work by his son, Melzar, who went on to have an accomplished career both designing and casting statues. He remained here at Ames until 1884, but subsequently left the firm and established his own foundry here in Chicopee.

Of the two Ames brothers, only James lived to see the company’s prosperity in the mid-19th century. Nathan died in 1847, at the age of 43, but James remained with the company until his retirement in 1872, a year before his death. However, by this point Ames Manufacturing was entering a decline. The Civil War had been a boon for business, but after the war the company struggled to adapt to peacetime demands. The factory produced a wide variety of metal products, from mailboxes to ice skates, and as late as the 1870s the company had major foreign contracts for bayonets, scabbards, and sabers. Starting in the early 1880s, Ames also produced bicycles for the Overman Wheel Company. This contract proved lucrative, as demand for bicycles skyrocketed during this period, but this high demand ultimately ended up hurting Ames when, in 1887, Overman opened its own bicycle factory in Chicopee Falls.

The first photo was taken several years later, by which point the company was in serious decline. Ames remained here for about 15 more years, but in 1908 the factory complex was sold to A. G. Spalding and Brothers. This sporting goods company had been established in Chicago in 1876 by baseball player Albert G. Spalding, and in 1893 the company began manufacturing its products in Chicopee Falls. After purchasing the Ames facility in 1908, Spalding set about expanding it, adding several new buildings, and for the next 40 years the factory produced a wide range of Spalding sporting goods. Among other things, Spalding supplied the baseballs for Major League Baseball for most of the 20th century, and these balls were produced here in Chicopee. Spalding was also an early leader in golf equipment, and at one point had an entire building dedicated to producing golf balls.

Spalding relocated to a new facility in Chicopee in 1948, but the old buildings continued to be used by a variety of industries until the 1980s, when the buildings were converted into a 138-unit apartment complex known as Ames Privilege. Despite the many changes in ownership and use, though, the former Ames facility has survived with few major changes over the years. It is hard to tell in the second photo, but the same buildings from the first photo still line the canal, and the only significant change is a fourth floor, which was added to the buildings sometime after the first photo was taken. Because of its level of preservation and its historical significance, the property was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.