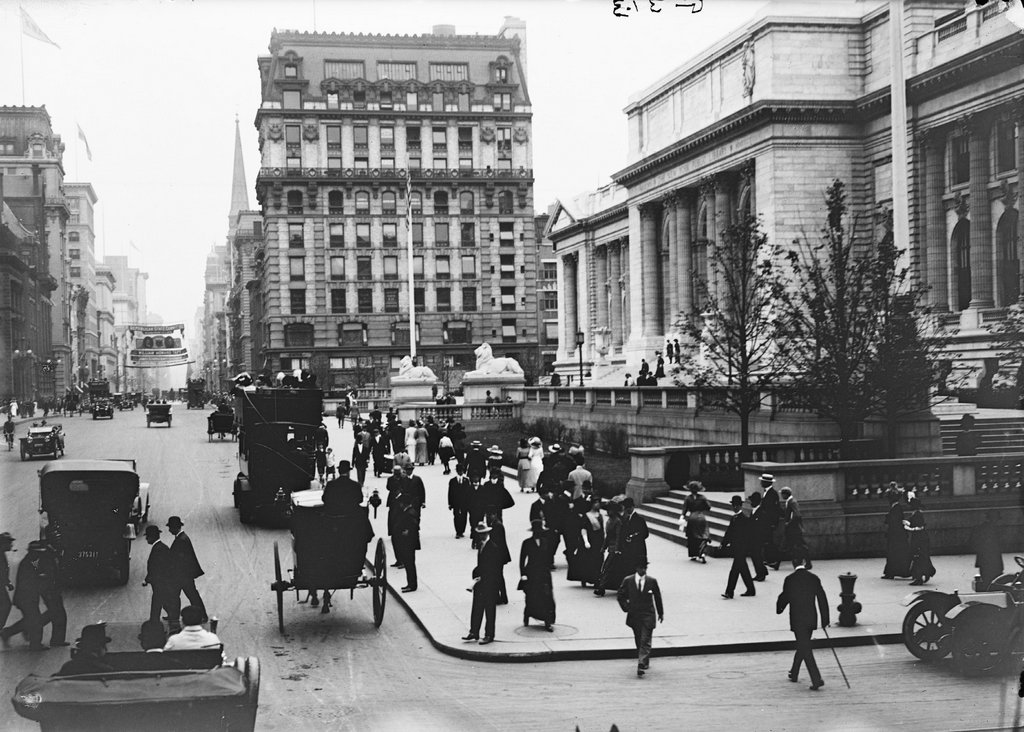

Looking north on Fifth Avenue from 51st Street in New York City, around 1900-1905. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The view in 2016:

In 1873, Mark Twain coined the phrase “Gilded Age,” which was later used to refer to the last few decades of the 19th century, which saw strong economic growth and vast fortunes, but also widespread poverty and other social issues. In New York City, perhaps nothing better represented the “gilding” of the era than the many homes of the Vanderbilt family, which were concentrated along this section of Fifth Avenue.

The Vanderbilt family’s wealth originated with Cornelius Vanderbilt, who was born in 1794 to a relatively poor family. When he was 16, he began operating his own ferry service on Staten Island, which he eventually grew into a massive transportation empire that consisted of steamboats, steamships, and railroads. By the time he died in 1877 at the age of 82, he had a net worth of about $105 million (over $2.3 billion today), nearly all of which he left to his oldest son, William Henry Vanderbilt. His younger son, Cornelius Jeremiah Vanderbilt, lacked his father’s business skills and squandered money on lavish spending and gambling. Because of this, his father left him a trust fund of just $200,000, which was a sizable amount of money for the time but just a fraction of a percent of his father’s wealth.

The younger Cornelius committed suicide several years later, but for his brother William the situation could not have been any different. While their father had lived relatively modestly, William and his children used their inheritance to build massive mansions along this section of Fifth Avenue, three of which appear in the first photo here.

On the left side of the photo is the Triple Palace, which consisted of three attached houses that occupied the entire block on the west side of the street between 51st and 52nd Streets. In this view, they appear to be two separate houses, but they were joined together in the back. William lived in the one on the left, and the section to the right was divided into two units, with his daughters Margaret and Emily living on the left and right sides, respectively. The family moved into the houses in 1881, although they were not completely finished until 1883. William had little time to enjoy it though; he died of a stroke just two years later, and after his wife’s death in 1896 their youngest son, George Washington Vanderbilt II, inherited the 58-room house.

The other Vanderbilt mansion in this scene is the house just to the right of the center of the photo, at the corner of 52nd Street. Known as the Petit Chateau, it was built in 1882 by William’s second-oldest son William Kissam Vanderbilt and his wife Alva Erskine Smith. They divorced in 1895, with Alva claiming infidelity. She received over $10 million (nearly $300 million today) plus substantial property, but William kept the Petit Chateau and lived here until his death in 1920.

When the first photo was taken, the mansions were barely 20 years old, but Fifth Avenue was already changing. The Petit Chateau was sold and demolished in the late 1920s, and the right side of the Triple Palace, where Margaret and Emily had lived, appears to have been demolished around the same time. By the 1940s, William H. Vanderbilt’s house on the far left was the only one remaining. His grandson, Cornelius Vanderbilt III, lived here with his wife Grace for many years, and even after the area became entirely commercial they still declined all offers from developers. Finally, he sold the house to the Astor family in 1940. They continued to live here until his death in 1942, and three years later the house was demolished.