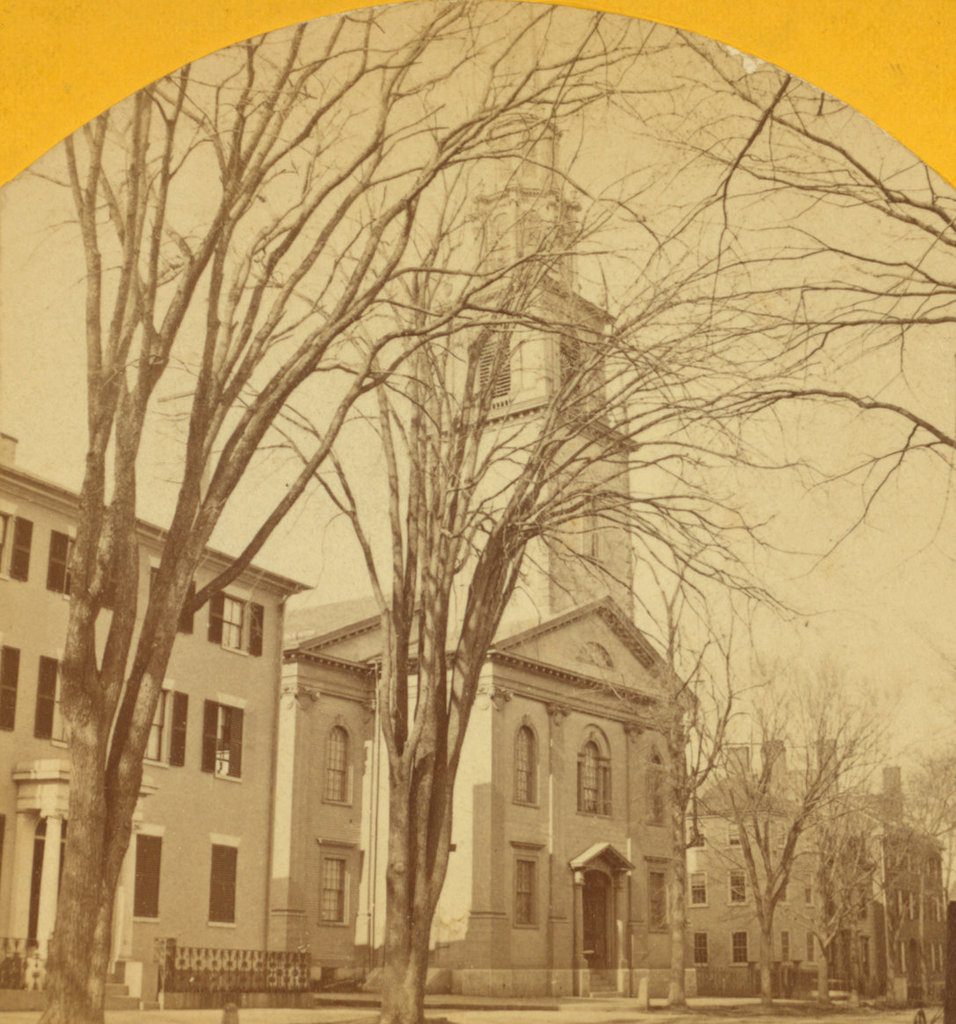

South Church, at the corner of Chestnut and Cambridge Streets in Salem, around 1865-1885. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

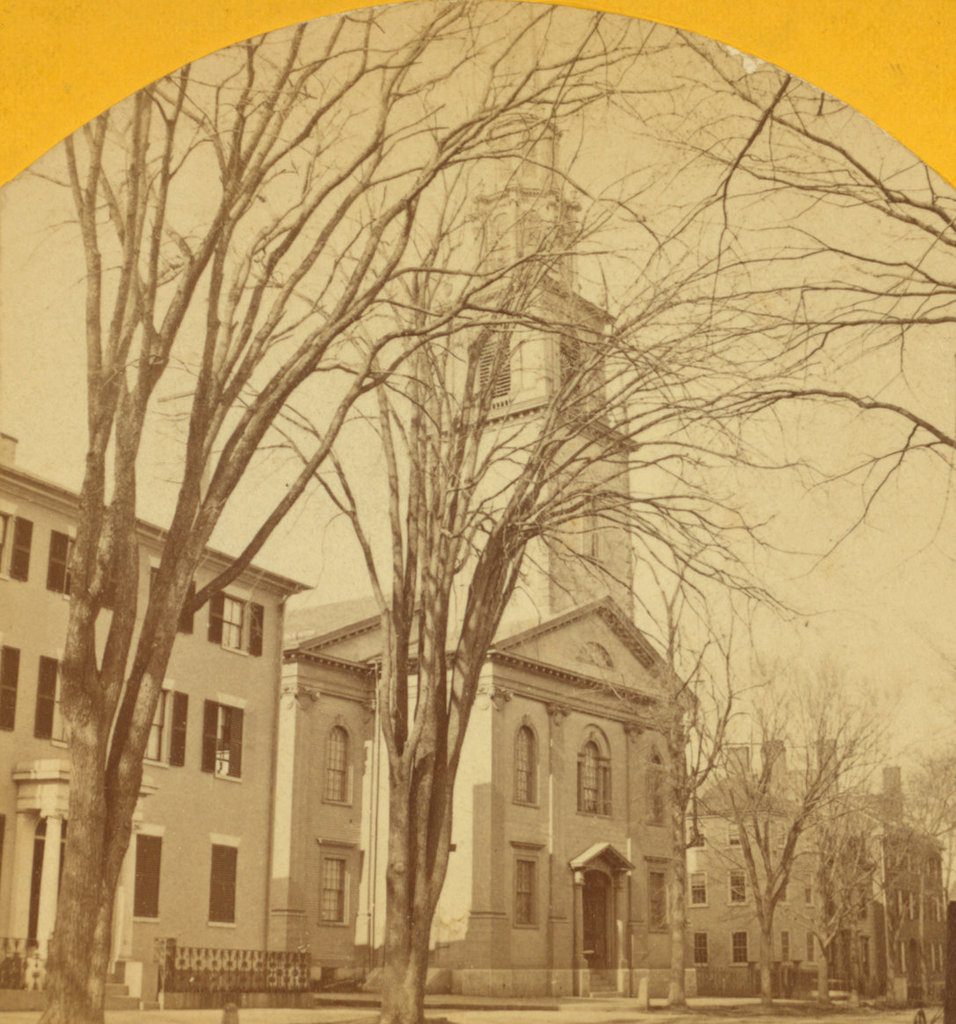

The scene in 2017:

The South Church was established in 1774, following a split within the Third Congregational Church, which later came to be known as the Tabernacle Congregational Church. For the first 30 years of its existence, the South Church met in a different building on Cambridge Street, but in 1804 construction began on a new church building here at the corner of Cambridge and Chestnut Streets. It was the work of prominent local architect Samuel McIntire, with an elegant Federal-style design that included elements such as pilasters on the front of the building, a Palladian window, a pediment above the front entrance, and an ornate, multi-stage steeple that rose from the top of the pediment.

The steeple in the first photo was actually the second one on the building. The first was destroyed in an apparent hurricane on September 11, 1804, in an event that was described by diarist William Bentley in his entry for that day:

The high wind brought down the unfinished Steeple of the new Meeting House lately raised in Cambridge Street, about five o’clock this afternoon. The whole work of the Steeple is distroyed. The spindle struck on the opposite side of the street, after falling 170 feet, about 30 feet from the building. The mortices had no pins through the long braces which went from the frame of the dome to the standard post & this occasioned the loss of the Steeple. The spindle broke, the vane and ball were much bruised & the whole a complete wreck.

However, the steeple was soon rebuilt to the height of 166 feet, and the building was dedicated on January 1, 1805, in a ceremony that was also described in Bentley’s diary:

This day was appropriated for the dedication of the New South Meeting House at Salem. A large Band of music was provided & Mr. [Samuel] Holyoke took the direction. A double bass, 5 bass viols, 5 violins, 2 Clarionets, 2 Bassoons & 5 german flutes composed the Instrumental music. About 80 singers, the greater part males, composed the vocal music. It could not have the refinement of taste as few of the singers were ever together before & most were instructed by different masters. But in these circumstances it was good. The House was crowded & not half that went were accomodated. Mr. Hopkins, the Pastor, performed the religious service of prayer & preaching, & a Mr. Emerson of Beverly made the last prayer. The music had an excellent dinner provided for them at the Ship [tavern] & the 16 ministers present dined in elegant taste at Hon. Jno. Norris Esqr. the principal character in the list of the Proprietors of the new Meeting House.

Later in the entry, Bentley also commented on the building’s architecture, writing:

The Steeple is the noblest in Town. Upon a lofty tower it rises upon reduced Octagons & hexagons, till it terminates in a slender cone. It is decorated handsomely. The roof is supported above, the arch is lofty, the pulpit rich, but nothing singular in the disposition of the House. It is the best structure for Public Worship ever raised in Salem.

The pastor at the time was Daniel Hopkins (1734-1814), a native of Waterbury, Connecticut who had graduated from Yale in 1758. He served as a delegate to the Third Provincial Congress of Massachusetts in 1775, shortly after the outbreak of the American Revolution, and he later served on the Governor’s Council from 1776 to 1778. He was ordained as the pastor of the South Church in 1778, and remained with the church until his death in 1814. However, he was suffering from poor health by the time this church building was completed, and in April 1805 he was joined by a second pastor, Brown Emerson (1778-1872), who had graduated from Dartmouth three years earlier.

In 1806, Brown Emerson married Reverend Hopkins’s daughter Mary, and went on to serve the church for many years after Hopkins’s death. Like Hopkins, he was also assisted by a younger pastor in his later years, but he remained with the church for a total of nearly 70 years, until his death in 1872 at the age of 94. Although the first photo is undated, it was probably taken sometime around the late 1860s or early 1870s, so it likely shows the church as it appeared around the time that Reverend Emerson died.

The historic church building stood here for nearly a century, until it was destroyed by a fire in 1903. It was a significant loss to the neighborhood, and was replaced by a stone, Gothic-style church that bore no resemblance to the old church, and it stood out as an anomaly among the otherwise Federal-style buildings on Chestnut Street. The new building was only used by the South Church for 20 years, until a 1924 merger with the Tabernacle Congregational Church. The building was subsequently used by a different church, but it was ultimately demolished in 1950, and the site was converted into a park.

Today, the former site of the church is still a park, as seen in the 2017 photo. However, aside from the loss of the church, the rest of the neighborhood has not undergone any significant changes since the area was first developed in the early 19th century. Just across the street from here is Hamilton Hall, which was built only a couple years after the original church building, and the homes in the first photo are also still standing, including the c.1808 Robinson-Little House on the left side of the scene. All of these buildings are now part of the Chestnut Street Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.