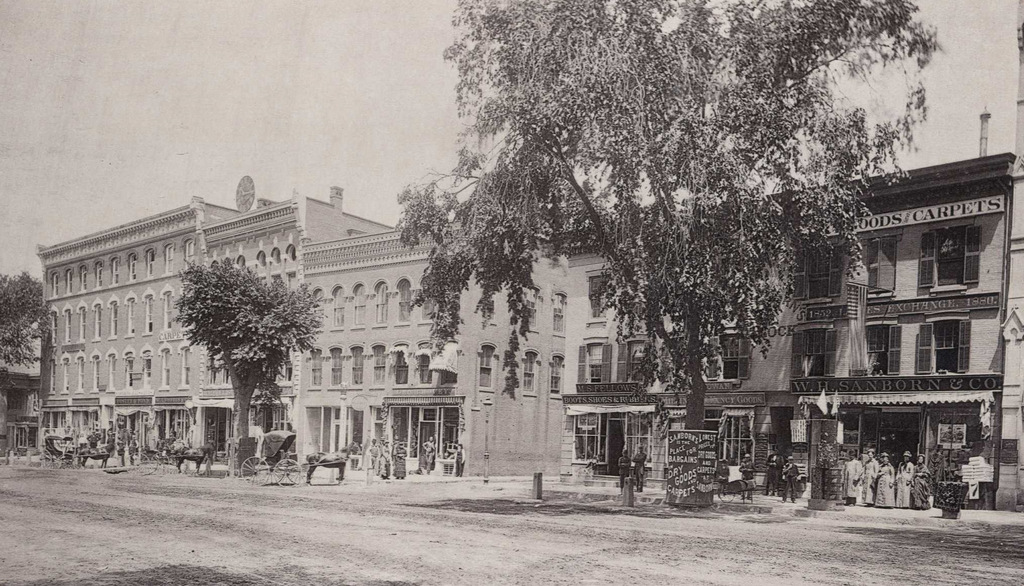

The American House at the corner of Main and Davis Streets in Greenfield, sometime around the 1880s. Photo from Greenfield Illustrated.

The scene in 2016:

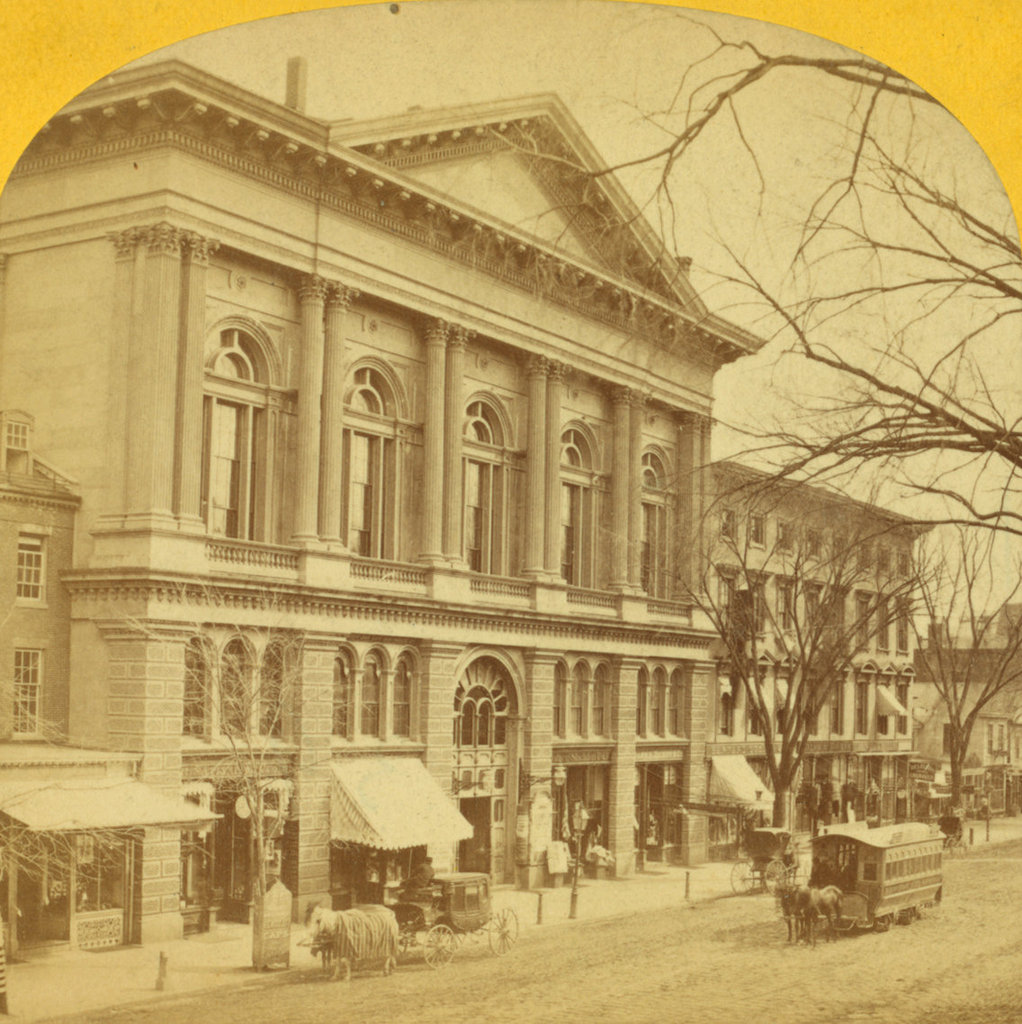

In modern-day redevelopments, architects often attempt to preserve the facades of old buildings, even if everything else is being demolished and rebuilt, and incorporate them into new structures. Especially in historic urban settings, this helps to maintain the visual appearance of the street while at the same time allowing a new building to occupy the site. However, in the 1960s the trend was the exact opposite. Many historic buildings had their original facades removed or covered, which the rest of the structure survived more or less intact underneath.

This was the case for several buildings along Greenfield’s historic Main Street, including this architectural monstrosity in the center of the photo. It was originally built in 1876, a few years before the first photo was taken, and was known as the American House. At the time it was Greenfield’s largest hotel, with a hundred guest rooms on the upper floors. The first floor had several stores, including a clothing store that was purchased in 1896 by John Wilson. He turned it into a department store and soon expanded into the second floor, and his business has remained here in the building ever since.

As for the hotel, it went through several other names, including the Devens Hotel and the Hotel Greenfield. Over time, though, the department store gradually expanded into the former hotel section. The building is still standing today, although it is completely unrecognizable from its original appearance. In 1965 its exterior was remodeled, with a metal facade that covered the original Italianate exterior. This original facade is probably still hiding under there, though, so perhaps someday the bland, warehouse-like exterior will be removed and the building restored to its 1870s appearance.

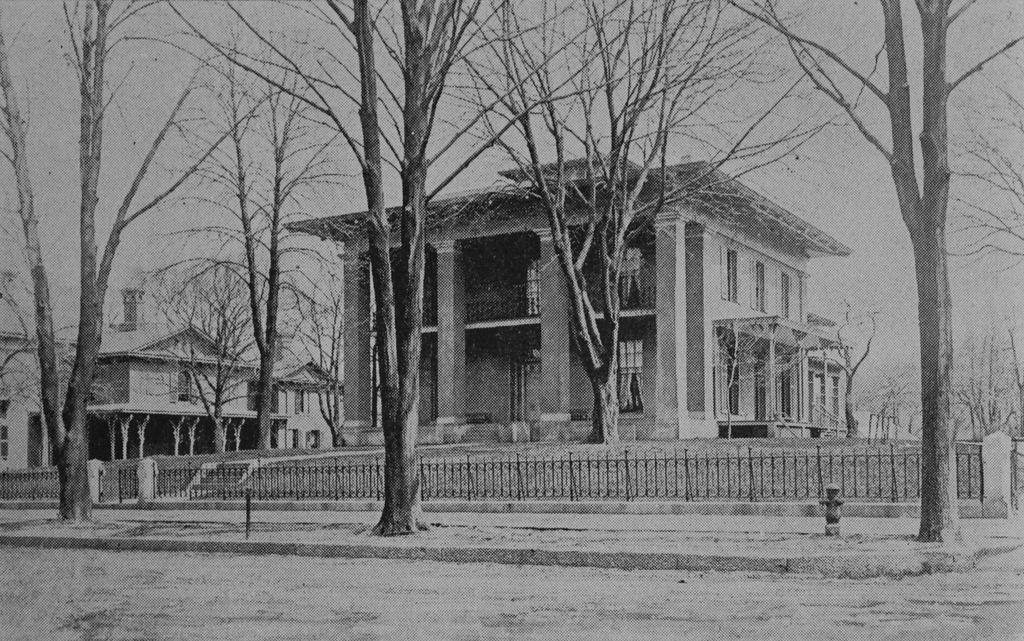

Although the American House has survived more or less intact under its mid-century shroud, the same cannot be said for the other historic building from the first photo, the Colonnade Block on the right. It was built in the 1790s as the home of Jerome Ripley, a prominent resident whose children included George Ripley, a Transcendentalist writer who founded the Brook Farm utopian community. In 1842, Dr. Daniel Hovey added the columns and portico to the front of the building, and for many years it was a commercial building known as the Colonnade Block. It stood here until 1975, when the 18th century structure was demolished to build a bank building, which is now a branch of Greenfield Community College.