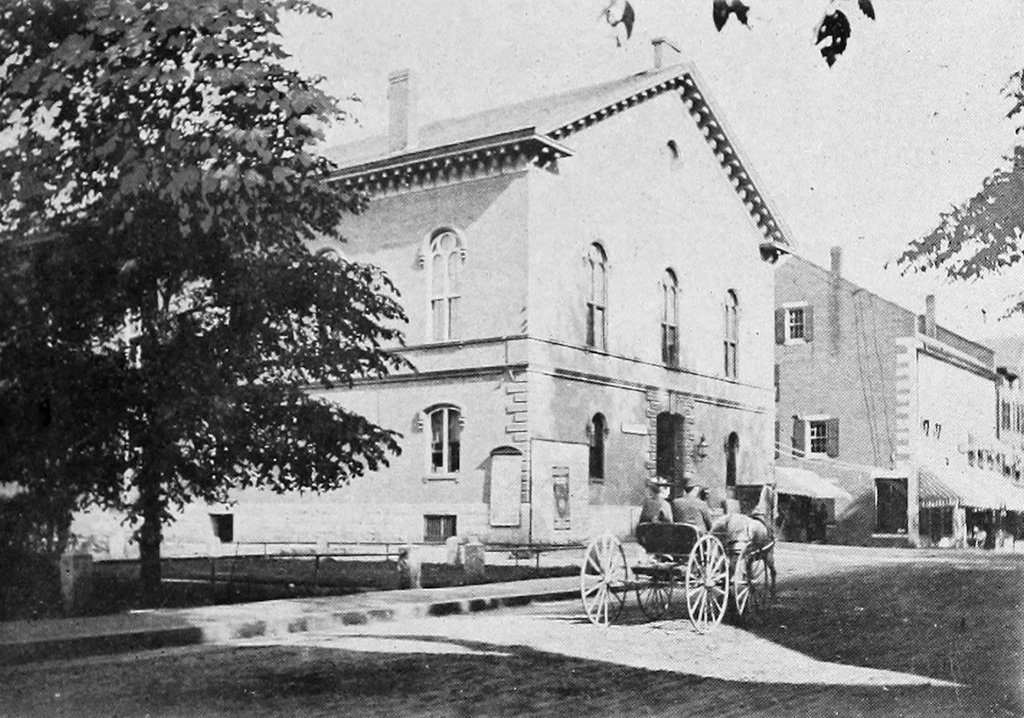

The old town hall on Main Street in Brattleboro, around 1894. Image from Picturesque Brattleboro (1894).

The scene in 2017:

The Brattleboro town hall was built here on Main Street in 1855, and served a wide variety of roles during its 98 years of existence. Aside from the town offices, this building housed the police department, post office, county clerk’s office, and library, and its hall was used for town meetings, concerts, theatrical performances, and other public events. The town also rented space in the building to private tenants, and over the years these included a bookstore, a dry goods store, and lawyers’ offices. Another tenant was William Morris Hunt, a prominent artist who had lived across the street from here as a child in the 1820s and early 1830s. He subsequently spent many years in Europe, but returned to Brattleboro for about a year in 1856, living in his old boyhood home and renting studio space here in the town hall.

The first photo was taken around 1894, nearly 40 years after the building was completed. The town hall had not changed much at that point, but about a year later it underwent an extensive renovation and expansion, which added an 875-seat opera house to the building. Like the original meeting hall in the building, this opera house was used for a variety of live performances, but by the early 1920s it had been converted into a movie theater, known as the Auditorium. Over the next few decades, though, the theater steadily declined, especially as newer, purpose-built movie theaters opened in downtown Brattleboro. In 1937, the building just to the right of the town hall was converted into the Paramount Theatre, and a year later the Latchis Theatre opened a few blocks to the south.

In the meantime, the building remained in use as the town hall until the early 1950s. However, in 1951 a new high school building opened in the southern part of town, leaving the old downtown school building vacant. The school was then converted into town offices, and the old town hall was sold. It was mostly demolished in 1953, although some of the exterior walls were left standing and were incorporated into the W. T. Grant department store, which was built on this site. This store is now long gone, but the one-story building remains, and still has some of the original walls of the town hall.

Aside from these walls, the only other surviving feature from the first photo is the building on the far right. Built around 1850, this commercial block is distinctive for its Main Street facade, which is made of granite blocks. The building was substantially altered when it was converted into the Paramount Theatre in 1937, including a large addition to the rear, a flat roof to replace the original gabled roof, and metal panels that covered the granite exterior. The building was gutted by a fire in 1991, but it was subsequently restored and is still standing today. Now that it no longer has the metal panels or the theater marquee, it looks more like its original appearance than it did for most of the 20th century, and despite the many changes it is still recognizable from the first photo.