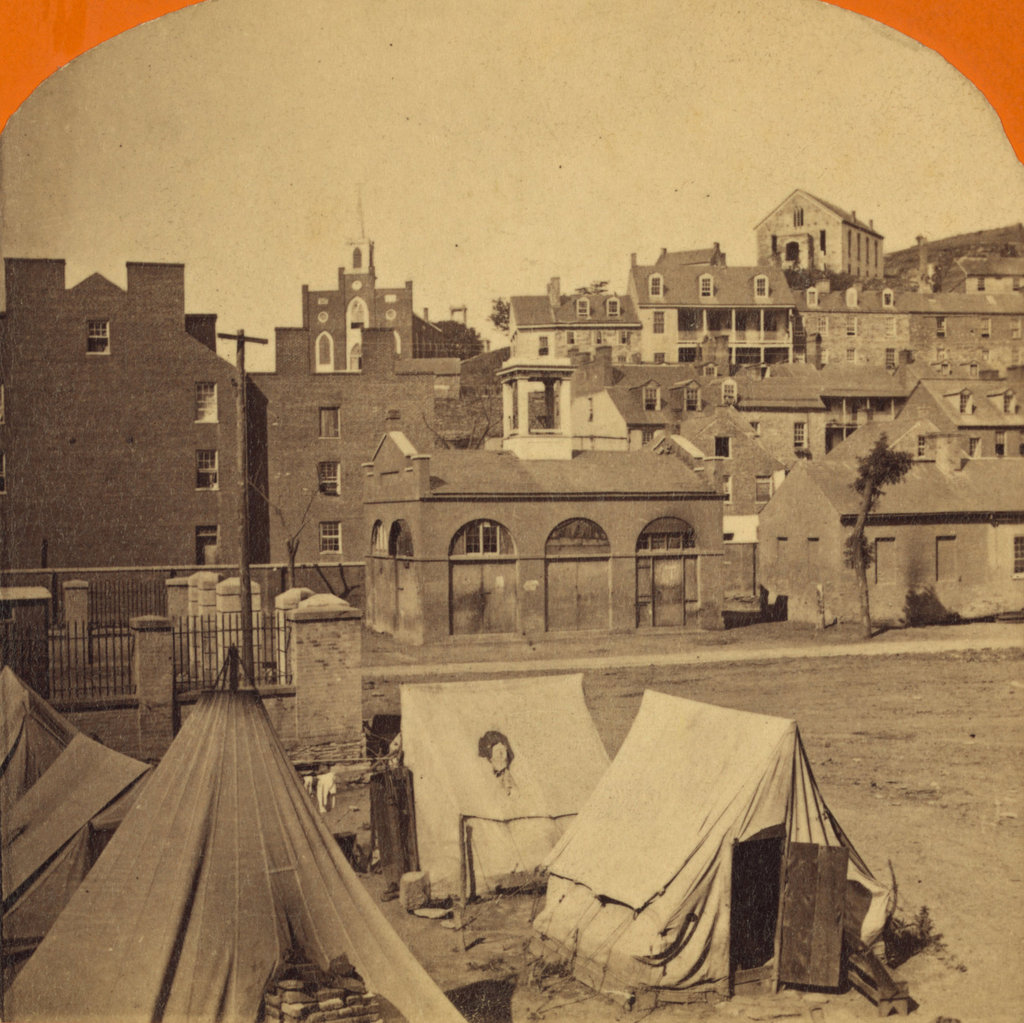

The town of Harpers Ferry, photographed around 1862. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Civil War Collection.

The view in 2015:

These two views of Harpers Ferry are remarkably similar, considering how much damage the small town sustained during the Civil War. The Library of Congress estimates that this photo was taken around 1860, which seems a little too early. This photo is half of a stereocard from a series called “War Views,” and since the war didn’t start until 1861, it seems unlikely that it was taken before then. Instead, it was probably taken around 1862; the tents in the foreground were part of a “contraband camp” that the Union army established on the grounds of the former armory in March 1862 to house escaped slaves from the Confederacy.

A number of notable buildings are visible here, with the most prominent being the Armory fire engine house, better known as “John Brown’s Fort,” seen in the center of the photo and explained in more detail in this post. To the left of the “fort” is the Gerard Bond Wager Building, a three and a half story brick building that was completed in 1838. Prior to the Civil War it was used as a grocery and dry goods store, and it is still standing today and is operated by the National Park Service as a museum.

Beyond the Gerard Bond Wager Building is St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church, which was built in 1833 and is still standing today, although with some extensive alterations. It survived the Civil War, but it was renovated in 1896 to bring its exterior in line with the then-popular Neo-Gothic architectural style. The original brick walls were replaced with granite, the steeple was removed, and a new asymmetrical facade was built with a taller steeple on the left side.

Another church in the original scene was St. John’s Episcopal Church, seen on the top of the hill to the right. It was built in 1852 and sustained damage during the war, eventually being repaired in 1882. However, it was subsequently abandoned in 1896, and today the picturesque ruins are still there, although they are hidden from view by the trees in the 2015 photo.

The last of the prominent historic buildings in these two photos are the four in a row next to each other, seen just below St. John’s Episcopal Church. All four are still standing today, and the left-most of these is the Harper House, which is the oldest surviving building in the lower town. It was completed in 1782 by Robert Harper, the town founder who not coincidentally operated a ferry here. He died the same year it was completed, and it was later used as a tavern, a private residence, and by the start of the Civil War as a tenement house, accommodating up to four families. To the right of the Harper House is Marmion Hall, which was completed in 1833, and the last two buildings to the right were built in the 1840s as the Marmion Tenant Houses. These last two were, prior to the war, rented out to armory workers, who were just a short downhill walk away from their jobs.

Today, railroad tracks cover much of the former armory site, and nearly all traces of the historic site are long gone. However, the town that grew up here because of the armory is, for the most part, preserved in its pre-1860s appearance. Much of the lower town is now part of the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, and is run by the National Park Service.