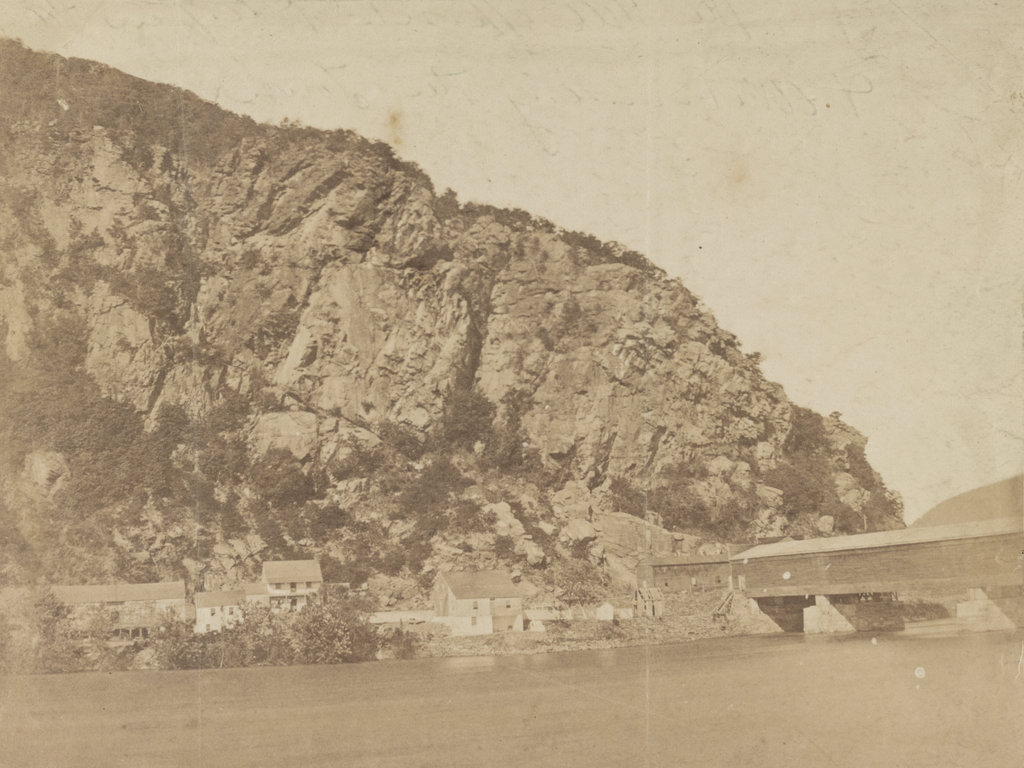

The ruins of the Harpers Ferry Armory, photographed in October 1862. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Civil War Collection.

The scene in 2015:

Prior to the Civil War, Harpers Ferry was the location of one of the country’s two federal armories, with the other being in Springfield, Massachusetts. Both sites were chosen by George Washington, and they had similar advantages. Harpers Ferry and Springfield are both located on major rivers at the intersection of major transportation routes, but they are also located above the head of navigation on their respective rivers, preventing a naval attack from a foreign enemy.

In the first half of the 19th century, these two armories developed new ways to manufacture firearms, using machinery that mass-produced identical, interchangeable parts and that could be operated by unskilled workers. By the start of the Civil War, there were over 15,000 guns stored here, which helped entice John Brown to lead a raiding party in 1859. His goal was to start a slave rebellion by taking the arsenal and distributing the weapons to area slaves, and although the plan failed, it helped to spark the Civil War only a year and a half later.

By the time the first photo had been taken in October 1862, Harpers Ferry had already changed hands a number of times in the Civil War, and armies on both sides had steadily destroyed the buildings in order to prevent the other side from making use of them. The ruins seen here are from the same building that can be seen on the right hand side of the 1861 photo in this post.

Around the time that the first photo was taken, the ruins had several notable visitors, including Abraham Lincoln, who toured the armory site in October, perhaps on the same day that the photo was taken. Author Nathaniel Hawthorne also visited Harpers Ferry earlier in 1862, and wrote the following description in his essay “Chiefly About War Matters”:

Immediately on the shore of the Potomac, and extending back towards the town, lay the dismal ruins of the United States arsenal and armory, consisting of piles of broken bricks and a waste of shapeless demolition, amid which we saw gun-barrels in heaps of hundreds together. They were the relics of conflagration, bent with the heat of fire, and rusted with the wintry rain to which they had since been exposed. The brightest sunshine could not have made the scene cheerful, nor have taken away from the gloom from the dilapidated town; for, besides the natural shabbiness, and decayed, unthrifty look of a Virginian village, it has an inexpressible forlorness resulting from the devastations of war and its occupation by both armies alternately.

The town became part of West Virginia in 1863, and things were relatively stable here until the end of the war. However, at that point the damage had been done. The pre-war economy of Harpers Ferry had relied almost exclusively on the armory, but it was never rebuilt following the war. The land was sold, and the Baltimore & Ohio built railroad tracks through part of the land, including the present-day railroad station, which was completed in 1889. Today, this area is part of the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, and although there are no buildings still standing here from the armory, the interpretive signs help to give visitors an idea of what was once here.