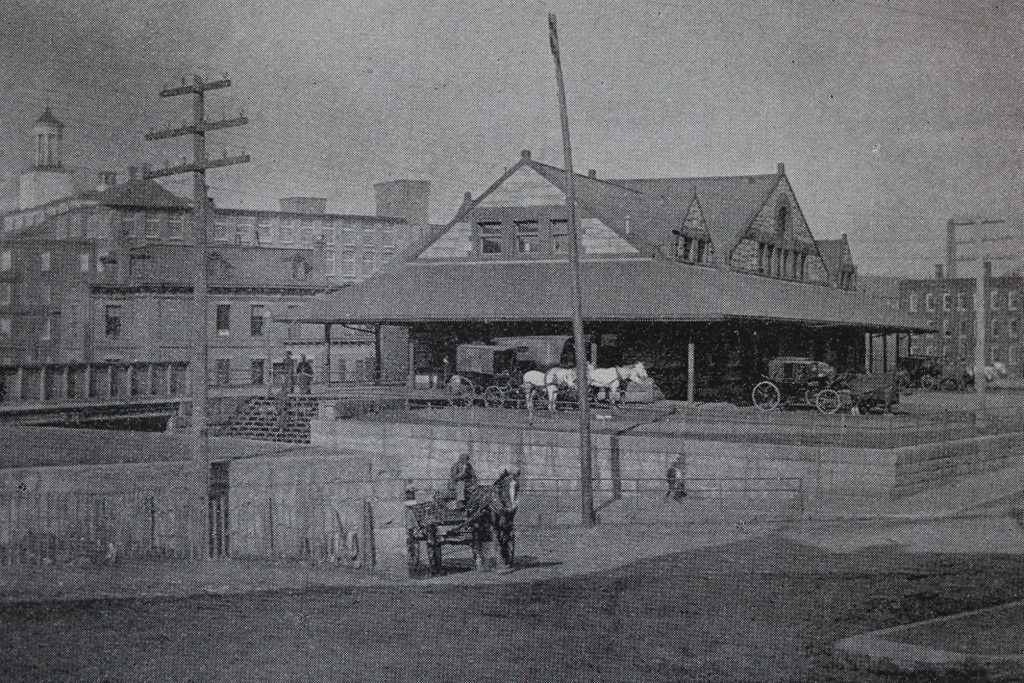

The Connecticut River Railroad station, seen from the corner of Bowers and Mosher Streets in Holyoke, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

The scene in 2017:

Railroads came to Holyoke in 1845, when the Connecticut River Railroad opened from Springfield to Northampton. This coincided with the area’s development into a major industrial center, and within a few years the canal system was completed and the first few mills were operational. The first passenger station was a small wood-frame building at the corner of Main and Dwight Streets, near where the modern Amtrak station is located, and it remained in use for about 40 years. However, Holyoke’s population grew exponentially during this time, from around 3,200 in the 1850 census, to over 21,000 by 1880, and the original station had become inadequate for the needs of the city.

In 1885, the Connecticut River Railroad opened a new passenger station here on the east side of the tracks, bounded by Mosher, Bowers, and Lyman Streets. It was designed by Henry H. Richardson, who was one of the most important American architects of the 19th century, and it was one of the many railroad stations that he designed across the state during the early 1880s. Richardson was a pioneer of Romanesque Revival style architecture, and his station incorporated many common elements, including the rough-faced granite exterior, the brownstone trim, a complex roofline, and arched windows.

On the interior, the central part of the station included the main waiting room, which occupied about half of the ground floor. There was also a separate ladies’ waiting room, and a room that, on the original floor plans, was labeled “Emigrant’s Room.” The latter was evidently used to screen and administer smallpox vaccinations to incoming immigrants, who comprised a large portion of Holyoke’s population during this time. Other facilities inside the building included a baggage room, a ticket office, and a telegraph office, along with several restrooms.

The first photo was taken around 1892, only a few years after the station was completed, and it shows the view from the southeast, from the corner of Bowers and Mosher Streets. About a year later, in 1893, the Connecticut River Railroad was acquired by the Boston and Maine Railroad, and the station became part of an extensive rail network that spread across northern New England. During this time, the station continued to play an important role as the point of arrival for many immigrants to Holyoke, including large numbers of French-Canadians who traveled south along the railroad from Quebec, in search of jobs in the factories here.

The station remained in use throughout the first half of the 20th century. However, Holyoke’s economy began to decline by the middle of the century, with many of the factories closing or relocating. Passenger rail travel suffered as well, both here in Holyoke and in the country as a whole. Cars and airplanes began replacing trains, and ridership continued to decline. The station closed in 1965, and passenger service on the line ended just a year later.

Following its closure, the former station was converted into an auto parts store, and at some point the platforms were enclosed on the southern side of the building. Passenger service would not return to Holyoke until 2015, after Amtrak’s Vermonter was rerouted through the city, but the plans did not involve restoration of the old station. Instead, a new one, consisting of just a single covered platform, opened a little to the south of here, near where the original 1845 station had stood. In the meantime, the old station has been vacant since at least the early 2000s. It is currently owned by Holyoke Gas and Electric, and has been the subject of various redevelopment proposals, although none of these have begun yet.