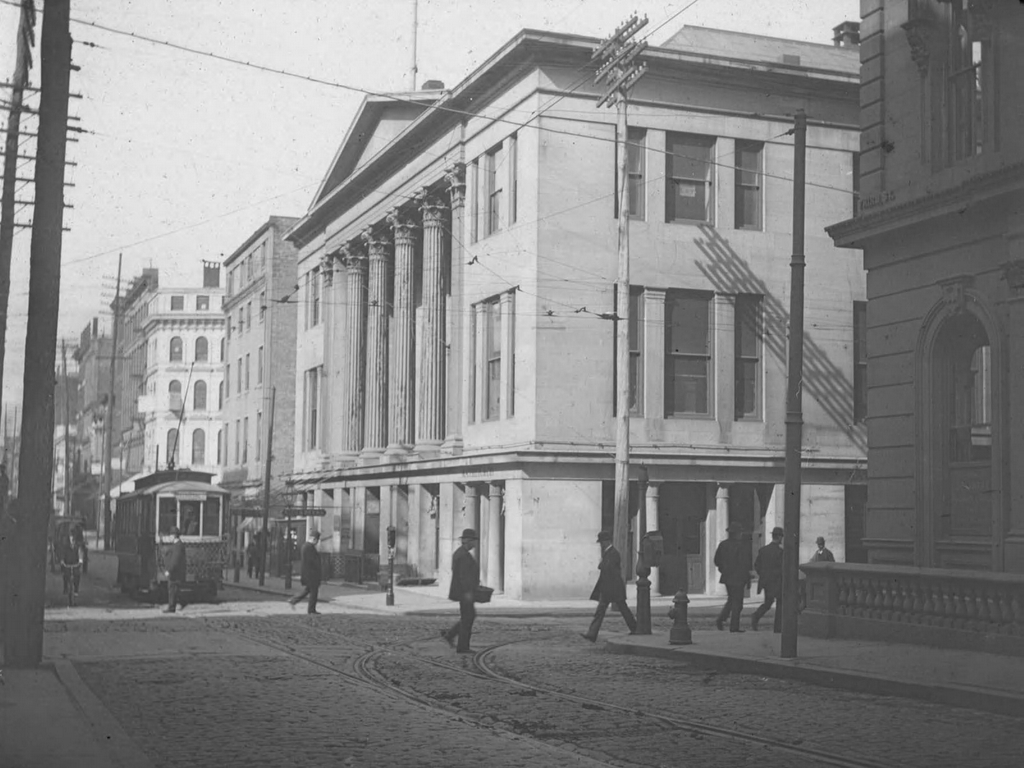

Nassau Hall at Princeton University, around 1903. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The building in 2019:

Nassau Hall, which opened in 1756, is the oldest building on the Princeton campus, and among the oldest college buildings in the United States. The College of New Jersey, as it was known at the time, was established in 1746, and it was originally located in Elizabeth before moving to Newark in 1747. Then, in 1753 Nathaniel FitzRandolph donated a plot of land here in Princeton to the school, and a year later the cornerstone was laid for this building. The building was nearly named for Governor Jonathan Belcher, but he demurred out of modesty, instead suggesting it be named Nassau Hall in honor of William III, who was from the House of Nassau.

Upon completion, Nassau Hall was one of the largest buildings in the English colonies, and the largest in New Jersey. It was the only building on campus at the time, so it was home to all of the school’s amenities, including a meeting hall, a dining room, offices, classrooms, and dormitory rooms. There were 70 students enrolled when the school moved here to Princeton, and its faculty consisted of the president, at the time Aaron Burr Sr., and two tutors. It was designed by Philadelphia architect Robert Smith, and one of the earliest descriptions of the building appeared in 1760 in the New American Magazine, which emphasized its rather spartan design:

There are three flat-arched doors on the north side giving access by a flight of steps to the three separate entries. At the center is a projecting section of five bays surmounted by a pediment with circular windows, and other decorations. The only ornamental feature above the cornice, is the cupola, standing somewhat higher than the twelve fireplace chimneys. Beyond these there are no features of distinction.

The simple interior design is shown in the plan, where a central corridor provided communication with the students’ chambers and recitation rooms, the entrances, and the common prayer hall; and on the second floor, with the library over the central north entrance. The prayer hall was two stories high, measured 32 by 40 feet, and had a balcony at the north end which could be reached from the second-story entry. Partially below ground level, though dimly lighted by windows, was the cellar, which served as kitchen, dining area (beneath the prayer hall), and storeroom. In all there were probably forty rooms for the students, not including those added later in the cellar when a moat was dug to allow additional light and air into that dungeon.

As was the case with most of the colonial-era colleges in the United States, the primary objective at the College of New Jersey was to prepare men to enter the ministry. However, while most were affiliated with either Puritanism or Anglicanism, this school was Presbyterian in its theology. Up until Woodrow Wilson in the early 20th century, all of its college presidents were ministers, and during the colonial era this included Great Awakening leader Jonathan Edwards and Declaration of Independence signer John Witherspoon.

Edwards arrived here in 1758, only two years after Nassau Hall was completed, but he died just a month later, after receiving a smallpox inoculation. The next two presidents also died relatively young, but John Witherspoon became president in 1768, and remained here until his death in 1794. During this time, he was also involved in politics, including serving on the Continental Congress, and he was the only clergyman among those who signed the Declaration of Independence.

Aside from these two presidents, the school also had a number of prominent students throughout the 18th century. Future president James Madison graduated from here in 1771, and one of his classmates was future vice president Aaron Burr, grandson of Jonathan Edwards, who graduated a year later. Others included Joseph Hewes, Benjamin Rush, and Richard Stockton, all of whom signed the Declaration of Independence along with Witherspoon.

After the end of the Revolution, ten Princetonians participated in the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, and five of them signed the Constitution: Gunning Bedford, David Brearley, Jonathan Dayton, James Madison, and William Paterson. Many other former Princeton students held other positions at the state and national level in the years during and immediately after the American Revolution. These included General Henry “Lighthorse Harry” Lee, who served as a cavalry officer in the Revolution and later as governor of Virginia, and Oliver Ellsworth, who served as the second Chief Justice of the United States.

However, it was not only Princeton’s students who played a role in the American Revolution; the school itself became a battleground during the Battle of Princeton on January 3, 1777. Prior to the battle, about 1,400 British soldiers were stationed in Princeton, and Nassau Hall was converted into barracks. During this time, the interior of the building was vandalized by the occupying army, and it was damaged even further during the battle itself. When Washington’s army advanced on Princeton, about 200 British soldiers took a defensive position inside of Nassau Hall, protected by the stone walls. However, the Continental Army opened fire on the building with cannons, and at least two cannonballs hit it before the British surrendered, effectively ending the battle.

Overall, the Battle of Princeton was a relatively small battle, but it helped to provide a much-needed morale boost for the Continental Army. Throughout the summer and fall of 1776, Washington had suffered a series of defeats as his army steadily retreated from New York City and across New Jersey. Thomas Paine famously described the situation as “the times that try men’s souls,” since many soldiers were deserting or not planning on re-enlisting after their enlistments expired on January 1, 1777. However, Washington’s surprise victory at Trenton on December 26, followed by Princeton a week later, helped to motivate soldiers to re-enlist and even inspired new recruits to join the army. Two years later, the Battle of Princeton was memorialized in Charles Willson Peale’s famous Washington at Princeton painting, depicting the commander in chief leaning against a cannon on the battlefield, with Nassau Hall visible in the distance on the left side of the painting.

Following the battle, Nassau Hall was occupied by the Continental Army throughout much of 1777, first as barracks and then as a hospital. This caused further damage to the interior, but at the end of the war the building took on a very different role when it temporarily became the capitol of the United States. Since 1775, Independence Hall in Philadelphia had been the meeting place of the Continental Congress. However, in 1783 a group of about 400 soldiers from the Continental Army marched on Independence Hall, demanding payment for their wartime service. Despite Congress’s requests, the Pennsylvania state government declined to use the militia to protect the building, so the Continental Congress left Philadelphia on June 21, and reconvened nine days later here at Princeton, in the second floor library of Nassau Hall.

Nassau Hall served as the capitol building for the next four months. During this time, on October 31, 1783, Congress was notified that British and American diplomats had signed the Treaty of Paris, ending the American Revolution. That same day, Congress also held a ceremony for diplomat Peter John van Berckel, who presented his credentials to Congress as the first Dutch ambassador to the United States. Van Berckel was apparently offended that his formal reception occurred in a small New Jersey town, rather than in Philadelphia as he had expected. However, he subsequently served as ambassador until 1788, and following the end of his term he continued to live in the United States for the rest of his life.

In any case, Congress did not remain in Princeton for much longer. It met here for the last time on November 4, 1783, and subsequently departed for Annapolis, where the Maryland State House functioned as the temporary national capitol. Congress would later return to the Princeton area, meeting in nearby Trenton for a little less than two months in late 1784 before moving to New York City in 1785. The capital city would then shift back to Philadelphia in 1790, before permanently moving to the newly-established city of Washington D.C. in 1800.

In the meantime, Nassau Hall continued to function as the home of the College of New Jersey throughout this time. However, on March 6, 1802 the building was completely gutted by a fire, leaving only the stone exterior walls still standing. The school soon began raising funds for its reconstruction, and among the donors were the citizens of Princeton, who feared that the school would use the opportunity to move out of the small town. For the work of rebuilding Nassau Hall, the school hired architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, who is best known for having designed the United States Capitol in Washington. His plans for Nassau Hall were largely faithful to Robert Smith’s original design, and consisted of mostly minor stylistic changes. Perhaps the greatest difference was the roof, which was raised two feet higher than the original.

Thus restored, Nassau Hall would continue to be occupied by the school for the next half century, until another disastrous fire gutted it on March 10, 1855. This time, architect John Notman was responsible for the renovations, in the process making more drastic changes than Latrobe had. Inspired by Italianate-style architecture, which was popular at the time, Notman’s plans gave Nassau Hall more of a Renaissance appearance. Here on this side of the building, his design included a new arched doorway at the main entrance, and an arched window and balcony above it. Notman’s most significant alteration, though, was the addition of two Italianate towers, with one at each end of the building. The tower on the east side of the building is hidden behind the trees in the first photo, but the western tower is partially visible on the far right side of the scene.

The first photo was taken around 1903, and just two years later the tops of these towers were removed. Otherwise, though, the exterior of the building has not changed much since the 1855 reconstruction. However, the school’s use of Nassau Hall has evolved during this time. As Princeton added new buildings to its campus, Nassau Hall no longer needed to serve as an all-in-one building for dormitory rooms, classrooms, and offices. By 1924, the building was being used exclusively for administrative offices, including the offices of the university president, and it has been used for this purpose ever since.

Today, after surviving a Revolutionary War battle and two major fires, Nassau Hall still stands as an important part of the Princeton campus. It has been heavily altered, especially after the two fires, and the only original materials left in the building are the stone walls. Regardless, though, it remains one of the oldest college buildings in the country, and it is also important for its role in the Battle of Princeton and as the temporary capitol of the United States. Because of this, Nassau Hall was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1960.