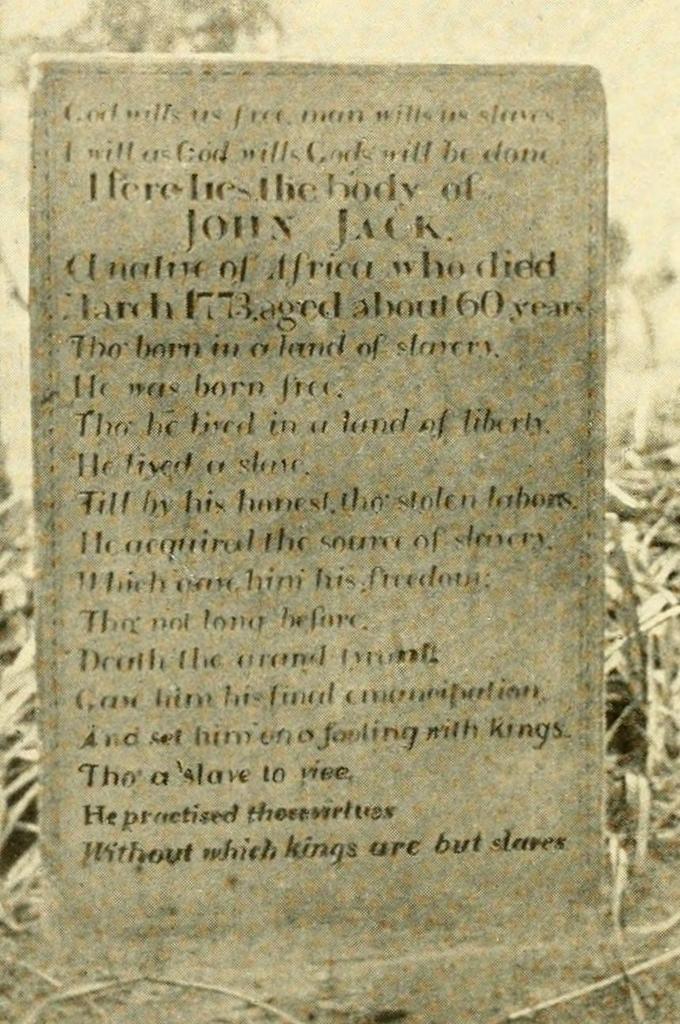

The gravestone of John Jack at Old Hill Burying Ground in Concord, around 1904. Image from The History of Concord, Massachusetts (1904).

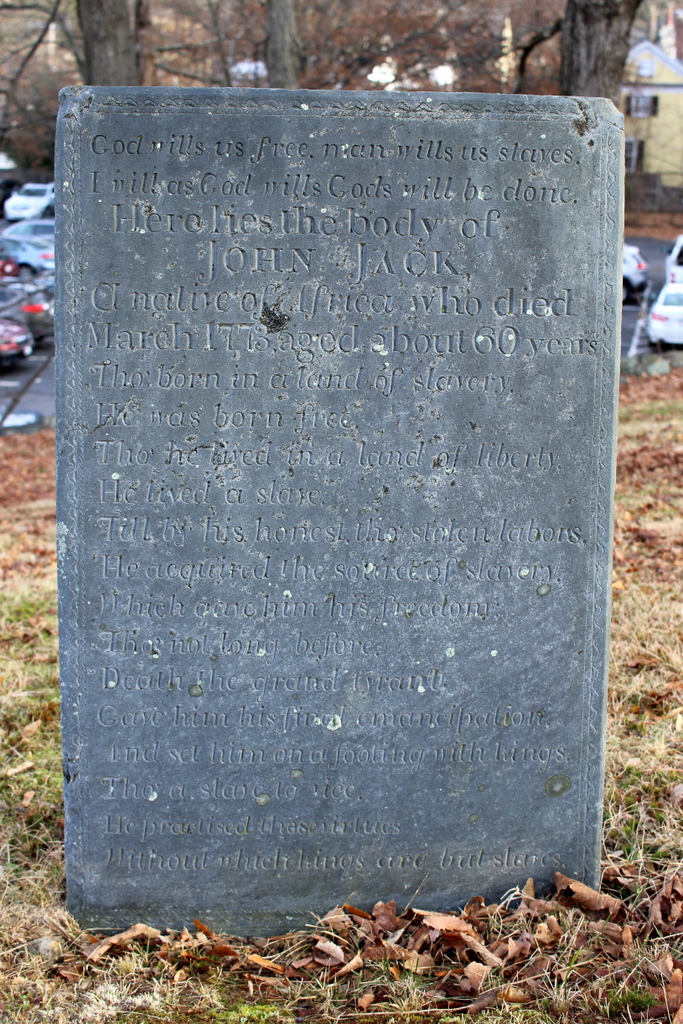

The gravestone in 2023:

It is rare to find surviving colonial-era gravestones for African Americans in New England. Although the region had a sizeable population of enslaved and free people of color during this time, most were buried in unmarked graves, often on the far edges of the town burial grounds. The few gravestones that do exist for enslaved people were apparently commissioned by the families that enslaved them, with inscriptions that often describe them as being their “servant.”

In this regard, the gravestone for John Jack is particularly unusual. Rather than simply identifying him as the servant of a master, the inscription tells the story of his enslavement and subsequent freedom, and in the process it delivers a striking rebuke of the institution of slavery. It reads:

God wills us free, man wills us slaves.

I will as God wills Gods will be done.

Here lies the body of

JOHN JACK.

A native of Africa who died

March 1773, aged about 60 years.

Tho’ born in a land of slavery,

He was born free.

Tho’ he lived in a land of liberty,

He lived a slave,

Till by his honest, tho’ stolen labors,

He acquired the source of slavery

Which gave him his freedom,

Tho’ not long before,

Death the grand tyrant

Gave him his final emancipation,

And set him on a footing with kings.

Tho’ a slave to vice,

He practised these virtues

Without which kings are but slaves.

As the epitaph indicates, John Jack was born in Africa, probably sometime around 1713. At some point he was kidnapped and sold into slavery, and by the 1750s he was in Concord, where he was enslaved to Benjamin Barron, a shoemaker. As an enslaved man, he did not have a surname. Instead, he was referred to in many historical records simply as Jack, or as Jack Negro. Barron died in 1754, and the inventory of his property included Jack, who was valued at 120 pounds, along with “One Negro maid named Vilot, being of no vallue.”

Jack later purchased his freedom, and by 1761 he had acquired enough wealth to become a landowner. That year, he purchased four acres from Benjamin’s daughter Susanna Barron, and he also purchased two more acres from another seller around the same time. He later bought another two and half acres and built his house on it. According to the 1902 essay John Jack, the Slave and Daniel Bliss, the Tory by George Tolman, John Jack did a variety of work for local farmers, including assisting with haying and pig slaughtering, and he also supposed himself by repairing shoes, a skill that he had likely learned during his time in slavery.

He died in March 1773, and in his will he left his entire estate “to Violet, a negro woman, commonly called Violet Barnes, and now dwelling with Susanna Barron of said Concord.” However, it seems unclear whether she actually benefitted from this bequest. Because she was still enslaved, she could not own property on her own, and any property given to her would instead have belonged to her enslaver.

John Jack’s death occurred right around the time that Revolutionary sentiment was rapidly growing in and around Boston. Many prominent figures spoke of ideals such as freedom and liberty, but in many cases they were also slaveowners, including Concord’s own minister, the Rev. William Emerson, who enslaved at least four people. This irony was not lost on some people, including Concord lawyer Daniel Bliss, who held loyalist views despite being the brother in law of Rev. Emerson, who was an outspoken patriot.

Shortly after John Jack’s death, Bliss commissioned this gravestone for him, and likely wrote the famous epitaph himself. The epitaph features a series of antithetical statements that, among other things, declare slavery to be a violation of God’s will and a contradiction to the values that the patriot leaders were expressing. There is a considerable amount of irony, such as how he was born free “in a land of slavery” but lived as a slave “in a land of liberty.” The epitaph also alludes to the “source of slavery,” (i.e. money), and how acquiring it ultimately resulted in gaining his freedom. But, despite his former status as a slave, the epitaph mentions how death is the great equalizer, and how he is now both slaves and kings ultimately share the same fate.

It did not take long for this epitaph to become famous. Supposedly, several British soldiers stopped by the burying ground on a visit to Concord in March 1775, and they copied the epitaph and sent it back across the Atlantic, where it was republished in British newspapers. By the late 18th century, the text of the epitaph was being published on a regular basis in American newspapers, especially after Massachusetts became the first state to abolish slavery in the 1780s. For example, Boston’s Independent Chronicle and the Universal Advertiser published it in 1791 at the request of a customer, who described it as “greatly admired by the curious, for its ingenious and striking antithesis.” This would continue into the 19th century, especially as abolitionist sentiment grew in the north.

The original gravestone stood here for nearly 50 years, but it was destroyed sometime in the late 1810s, evidently in an act of vandalism. The May 27, 1819 issue of the Middlesex Gazette reported that “[t]he following lines were inscribed on a stone, which was in good preservation, about two years since. Some person, or persons, however, from evil disposition, no doubt, have entirely demolished it.” The broken remains of the original stone laid here for about a decade, until lawyer Rufus Hosmer of Stow started an effort to replace it with a new stone. He and other members of the Middlesex County Bar Association collected funds, and around 1830 commissioned a new stone, which bears the same inscription as the original one. This is the stone that stands here today, and it is the one that is also shown in the top photo around the turn of the 20th century.

By the 1830s, the abolitionist movement had grown strong in Concord and in other places throughout New England. The new gravestone became an important symbol for local abolitionists, and the gravesite was maintained by Mary Rice, who planted lilies here, cleaned lichen off the gravestone, and trimmed the grass around the stone. In his 1902 essay, George Tolman described her as:

[A] little old gentlewoman who lived hard by; quaint in dress and blunt of speech, and with the kindest heart that ever beat; eccentric to a marked degree even among the eccentric people that Concord has always been popularly considered to abound in. She was devoted to all the “reform” causes of the day, and particularly to the anti-slavery movement, and was an active and enthusiastic agent of the “Underground Railway,” an institution by the way, of which Concord was one of the principal station. Many a fugitive found refuge, and, if needed, concealment, in her cottage or from her scanty purse was furnished the means to help him onward toward a free country. To her the epitaph of John Jack had a meaning; it was more than a mere series of brilliant antitheses; it was a prophecy and a promise. The humble grave upon the hillside was a holy sepulchre; its nameless tenant was the prophet and Messiah of the gospel of freedom.

Today, nearly 200 years after the replacement stone was installed here, it remains in good condition. It is made of durable slate, and its inscription is still easily legible, although the lighting was not ideal in the bottom photo. It stands as an important reminder of the history of slavery in New England, and of the contradictions that many Americans dealt with in trying to reconcile the revolutionary-era ideals of freedom and liberty with the practice of slavery. At the end of his essay on the gravestone, George Tolman expressed this quite eloquently in contrasting the stone to the other famous monuments here in Concord:

In the public square at Concord stands a monument to the memory of her sons who, in the late civil war, gave up their lives in defence of the principle of national freedom and unity; by the side of her quiet river her noble Minute-man keeps his unceasing watch over the spot where her sons stood to defend the principle of national independence. Both of these monuments are typical of political, and, in a sense, local and restricted ideas, narrow principles touching merely institutions and policies. But earlier than either, over the grave of a nameless slave in her ancient burying ground, stands the plain gray slab of slate that typifies the far higher idea which is of the constitution of humanity itself,—the principle of individual personal liberty.

We look in vain in the writings of speeches of our patriot fathers for any enunciation of this principle, for any condemnation of slavery as a sin against the moral government of the world. That was reserved for the man they called a Tory,—the man who believed that personal freedom was the God-given birthright of humanity, and whose clear and intelligent vision pierced through the mists of future years to the glorious time when that birthright should be everywhere acknowledged.

So the first picture of the plaque/headstone how big was it and what was it made of? I’m asking because I came across a wooden plaque that looks identical to it in a storage unit I’m cleaning out that belonged to an elderly lady. I can’t find anywhere that small plaques were made just like that?

Both photographs show the same physical gravestone, which has been here since about 1830. It is made of slate, and maybe about 3 feet tall. It is a very famous gravestone, so it is possible that someone might have made a rubbing of it and then create the plaque with it. Definitely an interesting find!

I didn’t pay much attention at first but it is like Slate not wooden and it says it was made in 1830 to replace the damaged original …so where do I take it to find a value of it and more information on it? Thanks for getting back to me

Can you tell me where I would be able to get a value of this Slate from?

This article was essential for me to comprehend the meaning of all the words inscribed on the gravestone. Those words are magnificent, and I am immensely grateful for this article – thank you to whoever published it! The bloke who authored the epitaph had astonishing insight, a supreme empath, an ability to encapsulate in few words an ocean of profundity. And the woman who tended to the gravestone was a heroine in life who, whether or not she was a Catholic (I can’t imagine she was), in sacrificing her life in the service of others to her own hurt, should rightly be beautified and straightway admitted to the venerated office of sainthood so that at least all Catholics over the whole world will be force-fed and confronted with the true nature of sainthood instead of the egregious confected bullshit & lies about every single one of their so-called “miracles”.