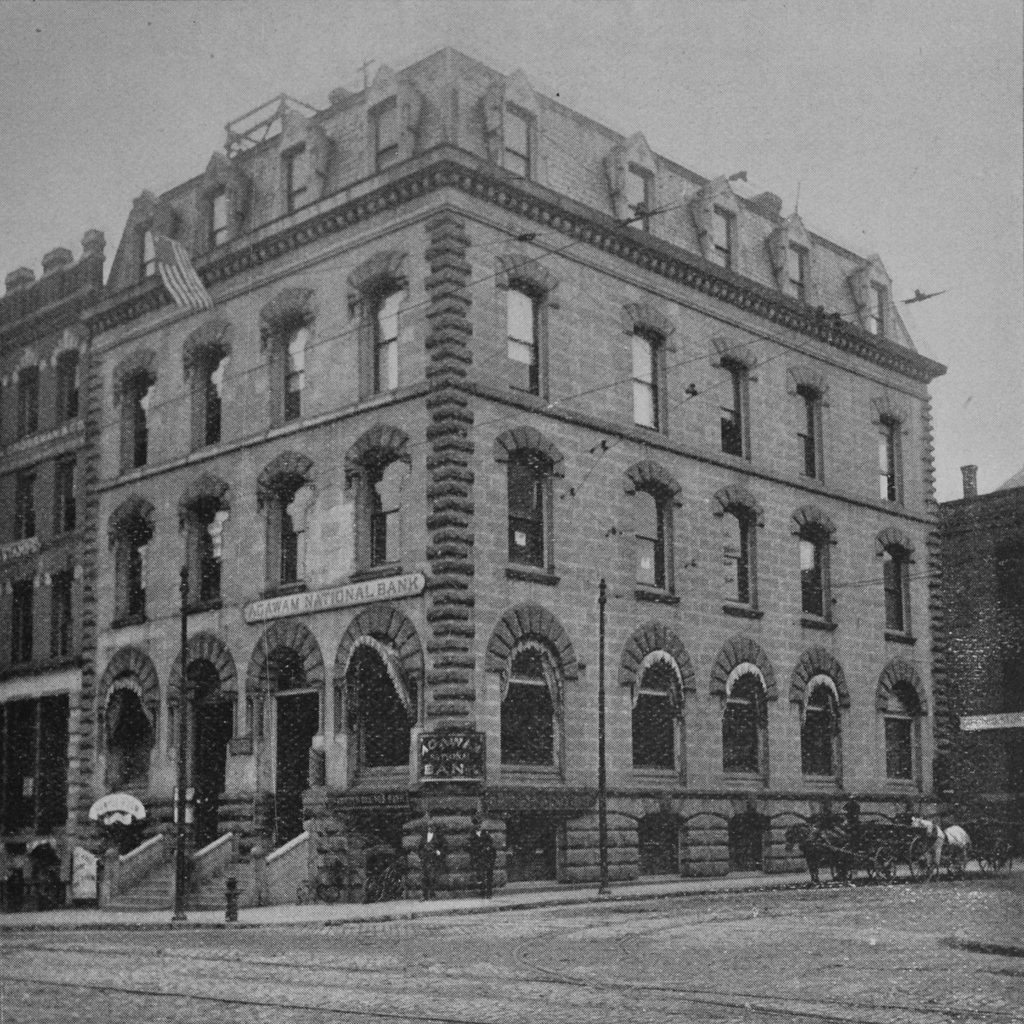

The former Second Bank of the United States, on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, around 1900-1906. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The building in 2019:

The establishment of a national bank was one of the most controversial economic matters in the early years of the United States government, pitting Federalists such as Alexander Hamilton against Democratic-Republicans such as Thomas Jefferson. The Federalists, who generally represented urban and northern interests, favored a strong central government in order to promote trade and industry, while the Democratic-Republicans, who were primarily southern and rural, saw such a government as a threat, instead preferring a decentralized, agrarian-based economy.

Over the objections of prominent figures such as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, the First Bank of the United States was established in 1791. At the time, the national capital was here in Philadelphia, with Congress meeting in Congress Hall, adjacent to Independence Hall. As a result, the bank was also headquartered in Philadelphia, where it operated out of Carpenters’ Hall until 1797, when a new bank building was completed nearby on South Third Street. The national government subsequently relocated to Washington, D.C. in 1800, but the bank remained in Philadelphia, and it continued to operate until 1811, when its twenty-year charter expired and Congress declined to renew it.

The country was without a national bank for the next five years, but in 1816 Congress authorized a new bank, the Second Bank of the United States. Ironically, this legislation was signed into law by President James Madison, who had come to recognize the need for a national bank after his earlier misgivings about the First Bank. Like its predecessor, the Second Bank was privately owned yet subject to government oversight, and its important roles included regulating public credit and stabilizing the national currency. This was particularly important in the years during and after the Madison administration, as the country recovered from the War of 1812 and began a series of ambitious internal improvements.

As with the First Bank, the Second Bank was located in Philadelphia, and it began operations in 1817. It also used Carpenters’ Hall as its temporary home, but in 1824 the bank moved into this newly-completed building on Chestnut Street. Designed by noted architect William Strickland, it features a Greek Revival exterior that is modeled on the Parthenon, with a pediment and eight Doric columns on both the north and south facades. This was an early example of Greek Revival architecture in the United States, and this style subsequently became very popular across the country in the next few decades, particularly for government and other institutional buildings.

By the time the building was completed in 1824, the bank had already faced significant criticism for its role in the Panic of 1819, the first major financial crisis in American history. Although part of a larger worldwide recession, it was also a consequence of the lending practices here at the Second Bank of the United States. Along with its role as the national bank, it also made loans to corporations and private individuals, and during its first few years it extended too much credit to borrowers. Then, in an effort to correct this, the bank began restricting credit, causing a nationwide rise in interest rates and unemployment, and a drop in property values and prices of farm produce. This ultimately triggered a financial panic in 1819, which was followed by an economic recession that lasted for several years.

The bank’s first two presidents were largely ineffective, but in 1823 Philadelphia native Nicholas Biddle became the bank president. He oversaw a slow but steady expansion of credit, along with an increase in banknotes, and during his tenure he managed to rehabilitate the bank’s image in the general public. This building on Chestnut Street opened about a year into his presidency, and he would continue to run the bank here for the next 12 years, until it closed in 1836 after its charter expired.

During these years, the bank — including its 25 branches across the country — played an important role in the nation’s economic growth. However, despite the bank’s success, it continued to generate controversy, becoming a central political issue during the presidency of Andrew Jackson. First elected in 1828, Jackson had a distrust of banks in general and the Second Bank of the United States in particular. He was skeptical of both paper money and lending, and he also opposed the bank on constitutional grounds. Echoing the earlier opposition to the First Bank, he argued that, as the Constitution does not explicitly authorize Congress to establish a national bank, it was an infringement upon the rights of the states.

In 1832, Congress approved a renewal of the bank’s charter, which was due to expire in four years. However, Jackson vetoed the bill, and Congress was unable to gather enough votes to override it. A year later, Jackson removed federal deposits from the bank and placed them into various state banks. Biddle subsequently made another effort to renew the charter, but despite his financial abilities he lacked strong political skills, and the bank’s charter ultimately expired in February 1836.

The bank itself did not close at this time, instead becoming the United States Bank of Philadelphia, with Nicholas Biddle still at the helm. However, the lack of a national bank soon became a factor in the Panic of 1837, which led to a seven-year recession. It was the worst economic crisis until the Great Depression, and it triggered a number of bank failures, including the United States Bank of Philadelphia. At the start of the recession, it had been the largest bank in the country, yet it ultimately went bankrupt in 1841.

A year later, Charles Dickens came to Philadelphia as part of his 1842 trip to the United States. He had few positive things to say about the country in his subsequent book, American Notes for General Circulation, and he painted a particularly bleak picture of the scene here at the old bank building with the following description:

We reached the city, late that night. Looking out of my chamber-window, before going to bed, I saw, on the opposite side of the way, a handsome building of white marble, which had a mournful ghost-like aspect, dreary to behold. I attributed this to the sombre influence of the night, and on rising in the morning looked out again, expecting to see its steps and portico thronged with groups of people passing in and out. The door was still tight shut, however; the same cold cheerless air prevailed: and the building looked as if the marble statue of Don Guzman could alone have any business to transact within its gloomy walls. I hastened to inquire its name and purpose, and then my surprise vanished. It was the Tomb of many fortunes; the Great Catacomb of investment; the memorable United States Bank.

The stoppage of this bank, with all its ruinous consequences, had cast (as I was told on every side) a gloom on Philadelphia, under the depressing effect of which it yet laboured. It certainly did seem rather dull and out of spirits.

As it turned out, the building did not remain vacant for very long. In 1845, it became the U. S. Custom House for the port of Philadelphia, and it was used in this capacity for far longer than it was ever used as a bank. It was still the Custom House when the first photo was taken at the turn of the 20th century, and this continued until 1934, when the present Custom House opened two blocks away. Then, in 1939, the old building was transferred to the National Park Service, which has owned it ever since.

The building has seen several different uses over the past 80 years, but it currently houses the Second Bank Portrait Gallery. It features a number of portraits by prominent late 18th and early 19th century artist Charles Willson Peale, including those of many important colonial-era leaders, such as John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton. Most of the interior has been heavily altered since its time as a bank, although the exterior has remained well-preserved, with few changes from its appearance in the first photo. It is now part of the Independence National Historical Park, and in 1987 it was designated as a National Historic Landmark.