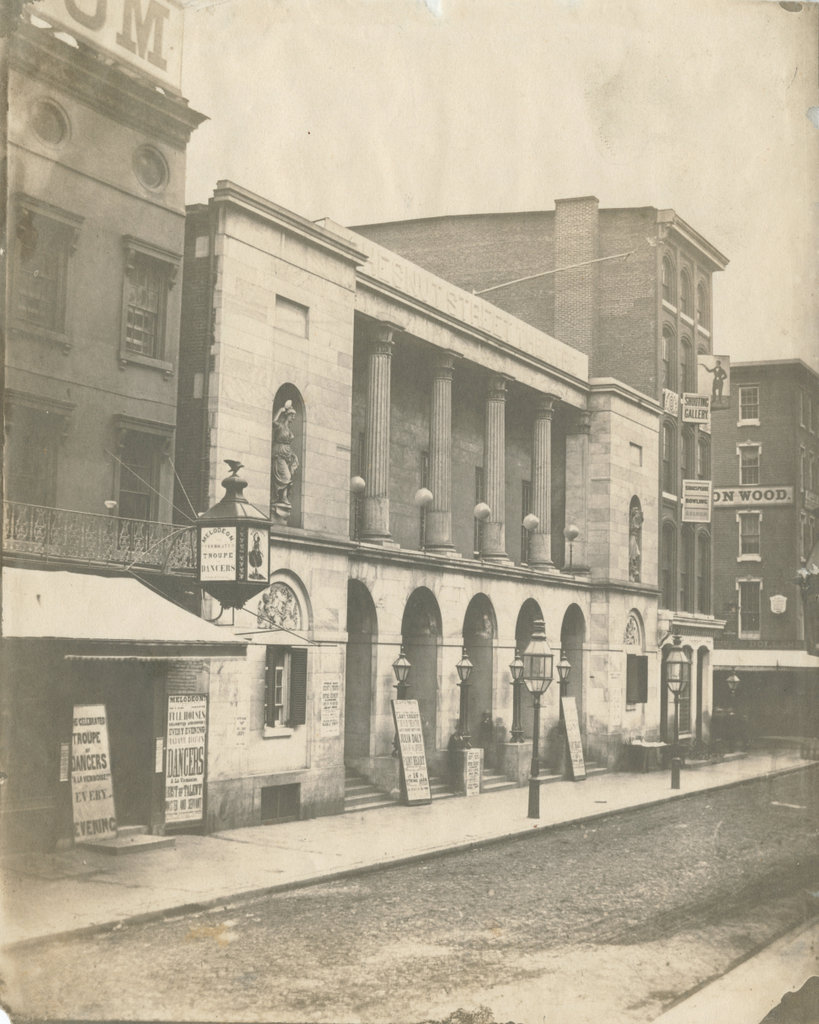

The presidential box at Ford’s Theatre, where Abraham Lincoln was shot on the night of April 14, 1865. This photo was taken several days later. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress. Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints collection.

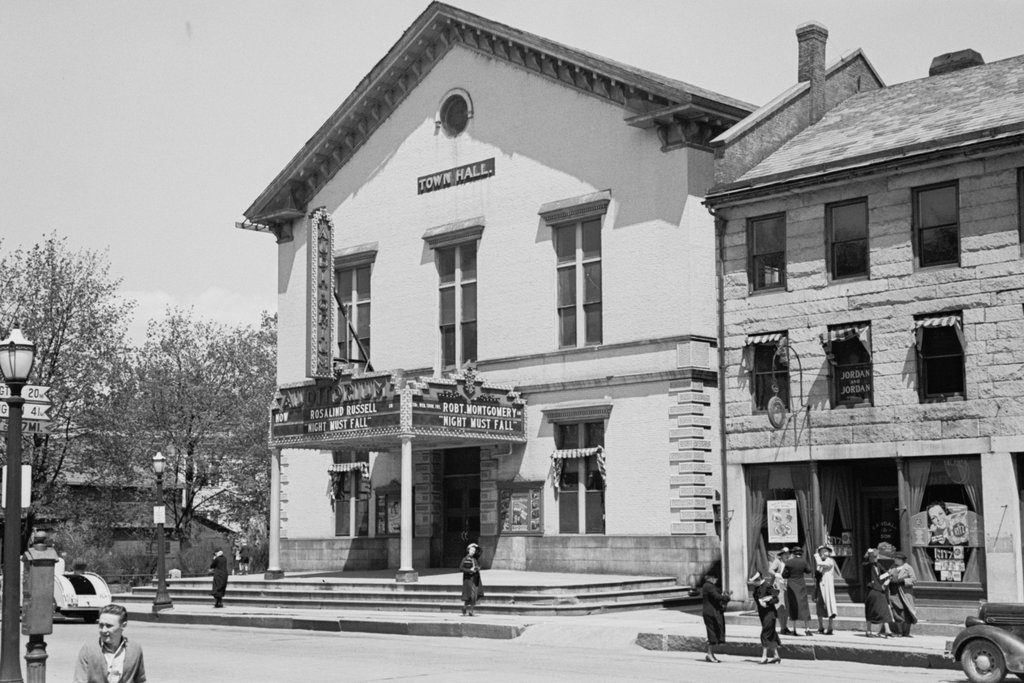

The scene in 2021:

These two photos show the presidential box at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., which is famous for having been the site of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865. Lincoln regularly attended performances here at Ford’s Theatre during his presidency, and on this particular night he was sitting in this box, watching the play Our American Cousin. He was accompanied by his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, along with Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée, Clara Harris.

Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, was a famous actor and a southern sympathizer. With the Civil War essentially over following the surrender of Lee’s army on April 9, Booth and his fellow conspirators evidently believed that killing Lincoln and other high-profile government officials was the last chance to prevent the defeat of the south.

To that end, Booth entered Ford’s Theatre at around 10:10 p.m. His presence in the theater raised little suspicion, since he was such a prominent actor, and he made his way to the presidential box. Not only was he familiar with the layout of the theater, but he also knew the play itself, and timed his shot so that it happened right after one of the funniest lines in the comedy, when he knew the sound of laughter would cover up the sound of the gunshot.

Booth entered the presidential box, produced a single-shot Deringer pistol, and shot Lincoln in the head at 10:15 p.m. He then had a brief struggle with Major Rathbone, whom he stabbed with a knife, and Booth then jumped down onto the stage, 12 feet below the box. In the process, he caught his riding spur in one of the flags that was draped on the front of the box, which caused him to land awkwardly. He then stood up, shouted “sic semper tyrannis,” and made his escape via a door on the side of the building.

In the meantime, 23-year-old Army surgeon Charles Leale was the first to arrive at the presidential box to render assistance. After evaluating Lincoln’s condition, he discovered the wound in the back of his head, and used his finger to remove a blood clot, which helped to improve his breathing. However, it was soon obvious that his wound was fatal, and that Lincoln would likely not survive a carriage ride back to the White House. Writing soon after the assassination, Dr. Leale described what occurred here in the presidential box in the immediate aftermath of the shooting;

I immediately ran to the Presidents box and as soon as the door was opened was admitted and introduced to Mrs. Lincoln when she exclaimed several times, “O Doctor, do what you can for him, do what you can”! I told her we would do all that we possibly could.

When I entered the box the ladies were very much excited. Mr. Lincoln was seated in a high backed arm-chair with his head leaning towards his right side supported by Mrs. Lincoln who was weeping bitterly. Miss Harris was near her left and behind the President.

While approaching the President I sent a gentleman for brandy and another for water.

When I reached the President he was in a state of general paralysis, his eyes were closed and he was in a profoundly comatose condition, while his breathing was intermittent and exceedingly stertorous. I placed my finger on his right radial pulse but could perceive no movement of the artery. As two gentlemen now arrived, I requested them to assist me to place him in a recumbent position, and as I held his head and shoulders, while doing this my hand came in contact with a clot of blood near his left shoulder.

Supposing that he had been stabbed there I asked a gentleman to cut his coat and shirt off from that part, to enable me if possible to check the hemorrhage which I supposed took place from the subclavian artery or some of its branches.

Before they had proceeded as far as the elbow I commenced to examine his head (as no wound near the shoulder was found) and soon passed my fingers over a large firm clot of blood situated about one inch below the superior curved line of the occipital bone.

The coagula I easily removed and passed the little finger of my left hand through the perfectly smooth opening made by the ball, and found that it had entered the encephalon.

As soon as I removed my finger a slight oozing of blood followed and his breathing became more regular and less stertorous. The brandy and water now arrived and a small quantity was placed in his mouth, which passed into his stomach where it was retained.

Dr. C. F. Taft and Dr. A. F. A. King now arrived and after a moments consultation we agreed to have him removed to the nearest house, which we immediately did, the above named with others assisting.

The nearest house proved to be the Petersen House, which was located directly across the street from the theater. The men carried him there, and laid him on a bed on the first floor. Over the course of the night, other physicians arrived to evaluate him, but there was little that they could do beyond removing blood clots. He died at 7:22 a.m. on April 15, without ever having regained consciousness following the shooting.

Lincoln’s death turned the Union’s victory at the end of the Civil War into a period of national mourning. Soldiers eventually tracked down Booth, who was killed in a shootout 12 days after the assassination, and the other conspirators were arrested, tried, convicted, and hanged on July 7.

Here at Ford’s Theatre, owner John T. Ford planned to reopen the theater on July 10, with a performance of Octoroon. Proceeds from the ticket sales would have gone toward a national monument fund for Lincoln, but many thought that it would be in poor taste to continue using the building as a theater. So, the War Department took control of the building prior to the performance, and the government began leasing it for $1,500 per month, before purchasing it outright from Ford in 1866.

The first photo was taken sometime in April 1865, only days after the assassination. It shows the presidential box as it had appeared on that night, including the five flags and the framed lithograph of George Washington that had decorated the box. Several of the chairs and the sofa are also visible inside the box. At the time of the assassination, Clara Harris had been sitting in one of the chairs on the left side, with Major Rathbone in the sofa. Mary Todd Lincoln and Abraham Lincoln had been sitting further to the right, and the chair on the right side of the box appears to have been the president’s rocking chair.

This photograph, along with a similar one taken at the same time, proved to be a valuable resource for historians. Soon after leasing the building, the government began the process of converting the interior of the theater into office space. This involved essentially gutting the building, and the presidential box was dismantled sometime in August 1865, about four months after the assassination. The project was completed in November, by which point the former theater had been transformed into a three-story government office building.

Over the next few decades, the building would house the Army Medical Museum, along with the War Department’s Division of Records and Pensions. However, as it turned out, the Lincoln assassination would not be the deadliest tragedy to occur in this building. By the 1890s, the building was showing signs of serious structural problems. These were exacerbated by excavation work in the basement, which weakened a load-bearing brick pier. This pier collapsed on June 9, 1893, causing a large section of the interior structure to collapse as well. Many government workers were trapped in the debris, and a total of 22 were killed in the disaster.

The interior of the building was subsequently repaired, and it continued to be used by the Division of Records and Pensions into the 20th century. By this point, though, there were increased calls to preserve the building as a museum and memorial in honor of Lincoln, rather than just using it for storing government records. Among those who advocated for such a plan was Congressman Henry Riggs Rathbone, the son of Major Rathbone and Clara Harris. He died in 1928, before any action had been taken, but in 1932 a Lincoln museum opened on the first floor of the former theater, featuring the extensive collection of Osborn H. Oldroyd, which had previously been housed across the street at the Petersen House. Then, a year later, the building came under the control of the National Park Service.

The building’s interior remained in its altered form until the mid-1960s, when it underwent a massive restoration. As was the case a century earlier, the interior of the building was gutted, leaving little more than the exterior walls still standing. The theater was then reconstructed inside the building, including the presidential box, which was furnished and decorated as it would have appeared on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. It reopened on January 30, 1968, with a nationally-televised event that included dignitaries such as Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey.

Today, Ford’s Theatre continues to be used as a performing arts venue, and it is also open to the public for tours. With the exception of modern wiring, this view of the presidential box looks essentially the same as it did in the first photo, although in reality there is probably nothing in the present-day scene that predates the 1960s restoration. However, some of the artifacts from the first photo do still exist. Three of the five flags are accounted for, with one in the museum here at Ford’s Theatre, one at the Connecticut Historical Society in Hartford, and one at the Pike County Historical Society in Milford, Pennsylvania. The door to the presidential box, the sofa, and the lithograph of Washington are also in the Ford’s Theatre collections, although the latter two are not on public display.

As for Lincoln’s rocking chair, it was taken by the government as evidence after the assassination, and it remained in storage for many years. But, in 1929 it was returned to the Blanche Ford, widow of the chair’s original owner, theater treasurer Henry C. Ford. She then sold it at auction, and the buyer in turn sold it to a different Henry Ford, of automobile fame, who was not related to the original owner. The chair is now on display at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan, where it is one of the highlights of the museum’s collections.