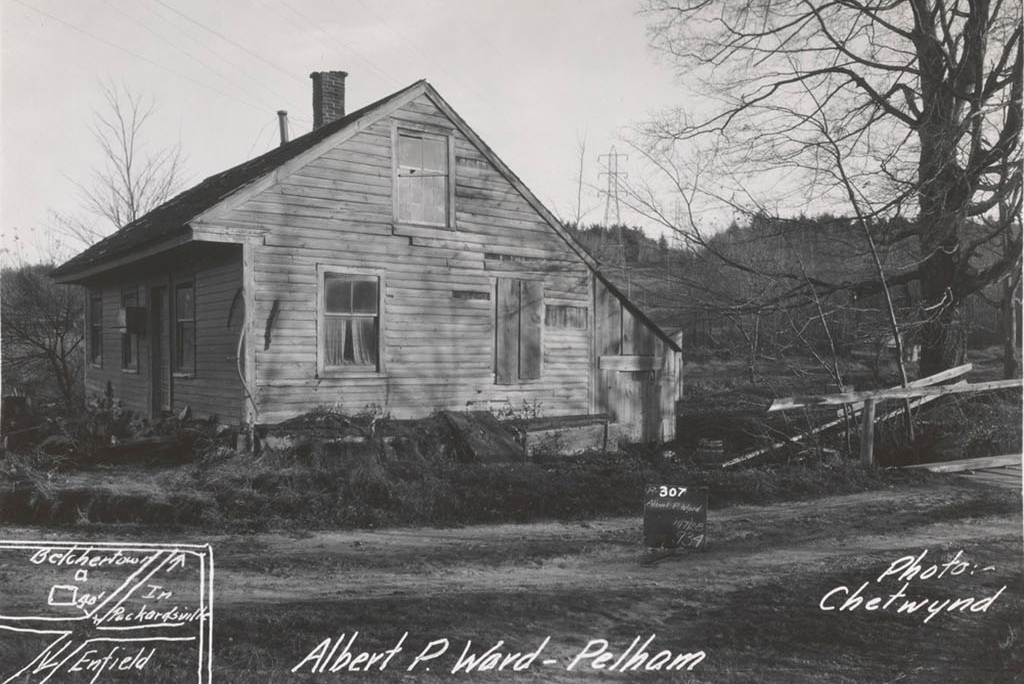

The house at the corner of Packardville Road and Juckett Road in Pelham, on November 7, 1928. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan District Water Supply Commission, Quabbin Reservoir, Photographs of Real Estate Takings.

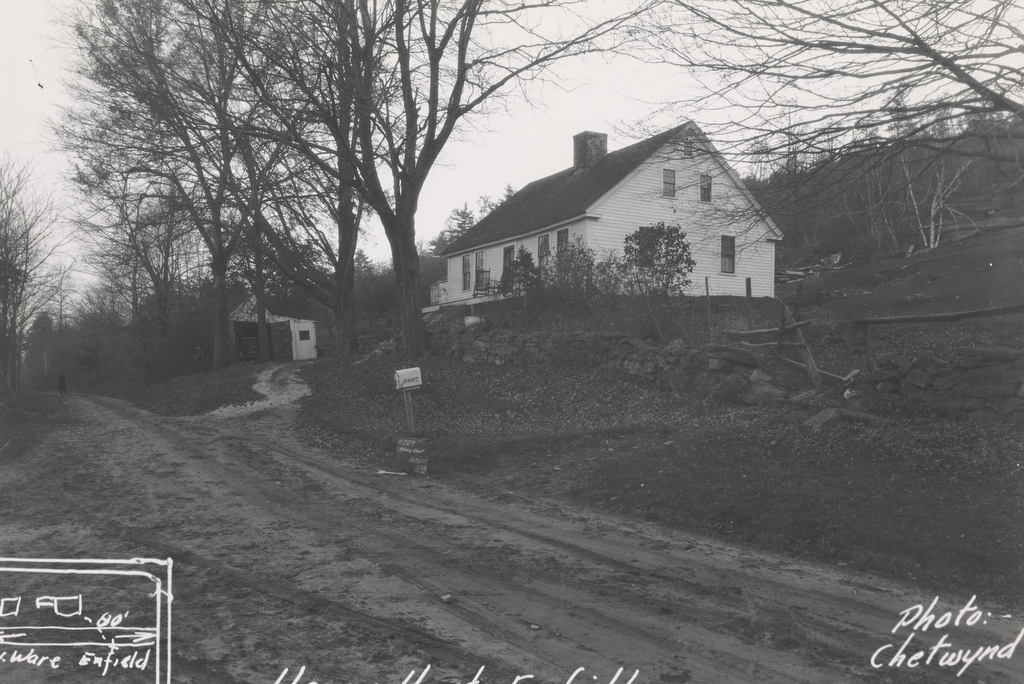

The scene in 2025:

This house was located at the southeast corner of the intersection of Packardville Road and Juckett Road, in the now defunct Pelham village of Packardville. It was owned briefly by Albert P. Ward, who acquired it as a gift from Henry Stevens in February of 1929. It was a small parcel that was broken off of a much larger property that Stevens owned. Ward’s newly created lot included only this house and an 8ft buffer around the home, for a lot size that totaled only 0.05 acres.

Before this home was built, a wagon shop for wagonmakers Packard & Thurston stood here in the early 1840s until they moved their operations to Belchertown in the late 1840s. Around 1860, this 1.5 story home was built by James Hanks, who owned and operated a store out of it from 1860 until 1873. Hanks would then go on to sell the home and the original, larger lot that it stood on to Henry Stevens in 1896.

Although the older photo labels this as the Albert P Ward House, he almost certainly never lived in it. Ward’s actual residence in 1929 was likely one of his properties in nearby Belchertown. The first photo was taken on November 7, 1928, three months before Ward was even gifted the property. Three months after Ward was given the home, the Massachusetts Metropolitan District Water Supply Commission would go on to purchase it from him in May of 1929 when building the Quabbin Reservoir. It is unclear why Ward was given this derelict looking home right before it would be sold again, or if he had a personal connection to it that predated his acquisition of it. The Water Supply Commission would demolish the home sometime in the early 1930s, because of its location inside the Quabbin Reservoir watershed.

Aside from a cellar hole where the home once stood, the site today has not changed much. The power lines, dirt roads, and small stream from the 1928 photo are still there. What were once small farms behind the home have long since grown in with trees and brush, and the road passing in front of the house no longer leads to a neighboring church.