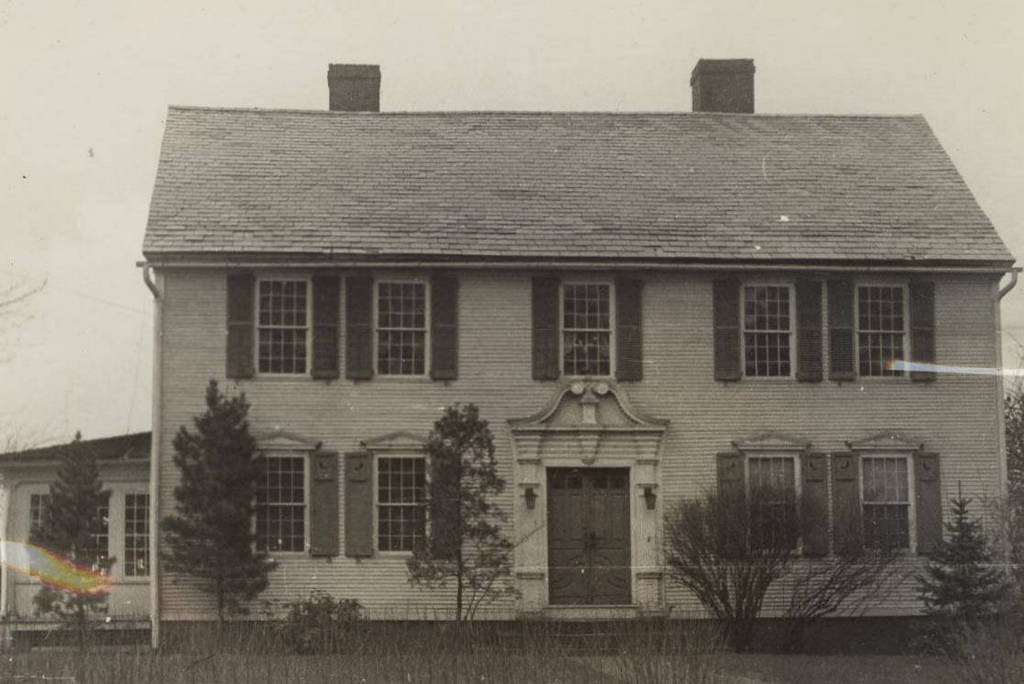

The house across from the corner of Skyline Trail and Bromley Road in Chester, Massachusetts, in April 1938. Photo by Arthur C. Haskell, courtesy of the Library of Congress, Historic American Buildings Survey Collection.

The scene in 2024:

This house is one of the oldest surviving buildings in Chester, and it was built in 1769 as the home of the Reverend Aaron Bascom, the first pastor of the town’s church. The town had been incorporated several years earlier in 1765, but it was originally named Murrayfield, although it was later renamed Chester in 1783. At the time, this area on modern-day Skyline Trail was the town center. It was located along a ridgeline of rolling hills between the Middle Branch and West Branch of the Westfield River, and it was fairly close to the geographic center of the town. The center consisted of the meeting house, a schoolhouse, Rev. Bascom’s house, and several other nearby homes.

Aaron Bascom was originally from Warren, Massachusetts. He graduated from Harvard in 1768, and a year later he accepted the position as the pastor of the church here in Murrayfield. He was ordained on December 20, 1769, at the age of 23. According to the 1963 publication The First Congregational Church of Chester, his compensation included an initial settlement of 70 pounds, along with an annual salary of 40 pounds for three years, which would then increase five pounds per year until it reached 60 pounds. In addition, he was provided with firewood and, most significantly, a house, which is shown here in these two photos.

The house is typical for mid-18th century homes in Massachusetts. It features a front façade with four windows and a central door on the first floor, and five windows on the second floor. It originally had a large central chimney, but as was often the case, this chimney was later removed in order to create more space for a staircase and entry hall. Over the years, the exterior of the house also saw alterations and additions. The shutters in the top photo would not have been original to the house, and it seems likely that the Greek Revival style front entryway was probably a mid-19th century alteration.

Aaron Bascom lived here until his death in 1814, and the house was later purchased by Dr. Thaddeus Kingsley DeWolf in 1832. He was a noted local physician, and he lived here with his first wife Correlia Benham and their children Oscar, Homer, Sarah, and Martha. Correlia died of dysentery on August 7, 1847, and young Martha likewise died of dysentery five days later. However, Dr. DeWolf remarried rather quickly. Less than two months later, on September 28, the 46-year-old widower married 19-year-old Mary Phelps. They had two children together: Henry Clay DeWolf, who was born in 1850; and DeWitt Clinton DeWolf, who was born in 1864. DeWitt is known to have been born in this house, and the older children presumably were as well.

By the time the younger children were born, the town of Chester had undergone significant changes. In 1841 the Western Railroad was built along the West Branch of the Westfield River, in the southern and western part of the town. This spurred new developments in the valley, with the village of Chester Factories eventually becoming the town center, in place of the old town center here on Chester Hill, as it came to be called.

This shift was part of a broader trend in the rural hilltowns of Western Massachusetts. With more productive farmland available in the west, and new opportunities in the nation’s industrial cities, many towns and villages experienced population decline in the second half of the 19th century. Among those who left the area was Dr. DeWolf’s oldest son Oscar. He went to medical school, served as a surgeon in the U.S. Army during the Civil War, and then moved to Northampton before relocating to Chicago in 1873. There he became the city’s commissioner of health, a position that he held for 14 years.

During that time, Oscar’s younger half brother DeWitt joined him in Chicago, moving to the city around the late 1870s when he was 15. Rather than pursuing medicine like his father and brother, DeWitt went into business. He first worked for a shoe company, but then became involved in the coal industry, eventually serving as president of one coal company and vice president of another.

However, both brothers would eventually return home to Chester in their later years. Oscar left Chicago in 1891 and moved to London, where he practiced medicine for 12 years before retiring and moving back across the Atlantic to his old hometown. He had inherited the family home after his father’s death in 1890, and the 1894 county atlas indicated that he owned several other nearby homes. When he returned to Chester in 1903, he appears to have moved into the neighboring home at 346 Skyline Trail, which still stands just to the left of the old house, out of view in these photos.

Oscar DeWolf died in 1910, and then in 1915 his brother DeWitt moved back to Chester. Because DeWitt owned multiple properties, none of which had street numbers at the time, it is difficult to trace exactly where he lived, but it was apparently either his birthplace house here in these photos, or in the house next door that his brother had lived in. It seems that, over the course of his 20 years in Chester, he may have lived in both houses at different times.

The 1920 census does not indicate which house DeWitt DeWolf was living in, but it shows him in Chester with his wife Harriet and their daughters Elsie, Louise, and Virginia. Their household also included James H. Ellis, who was listed as a lodger. He later married their oldest daughter Elsie in 1926.

Shortly after his return to Chester, DeWitt DeWolf became involved in politics. He served in a variety of town offices, but he was also active in the state’s Democratic Party. He was a delegate at the Democratic National Convention in 1924 and again in 1928, and both times he was a strong advocate for New York Governor Al Smith, who earned the party’s nomination in 1928 but ultimately lost to Herbert Hoover in the general election. During the 1930 state gubernatorial election, DeWitt campaigned on behalf of his friend Joseph B. Ely of Westfield. Ely won the election, and he served as governor from 1931 to 1935. Upon taking office, Ely appointed DeWitt as his executive secretary, and DeWitt later became the state commissioner of labor and industries.

Despite working on Beacon Hill, DeWitt DeWolf continued to live here in Chester. His wife Harriet had died in 1922, and by 1930 he was living alone, probably in the house next door to this one. A 1930 article in the Springfield Republican, written after his appointment as executive secretary to Governor-elect Ely, indicated that his daughter Elsie was living in the old house, and also implied that DeWitt was not living in it at the time. However, DeWitt died in 1935, and the newspaper coverage stated that he died in the house where he was born, suggesting that at some point before his death he moved back into the old house.

The top photo was taken in April 1938, a few years after DeWitt’s death. The family still owned the house at this point, and the outbuilding on the left even had a sign that said “DeWitt C. DeWolf.” The building was photographed as part of the Historic American Buildings Survey, a Depression-era federal program that documented historic resources across the country.

The property was evidently sold a few months after the photo was taken, based on an auction notice that was published in the Republican in September 1938. The house would subsequently change hands several more times over the course of the 20th century, and in 1988 it was added to the National Register of Historic Places as a contributing property in the Chester Center Historic District. This historic district is comprised of several other historic 18th and early 19th century buildings that all date back to when this small village was the town center.

The photographs that accompanied the National Register nomination form in the 1980s show the exterior of the house in reasonably good repair. However, the house has since been vacant for many years. All of the barns and other outbuildings are now gone, the property is overgrown, and the house itself is badly deteriorated. As shown in the second photo, the ground floor windows and doors are boarded up, and there is a sign next to the front door from the board of health, stating that it is unfit for human habitation. It is an important historic house, but in its current condition it is in danger of being permanently lost.