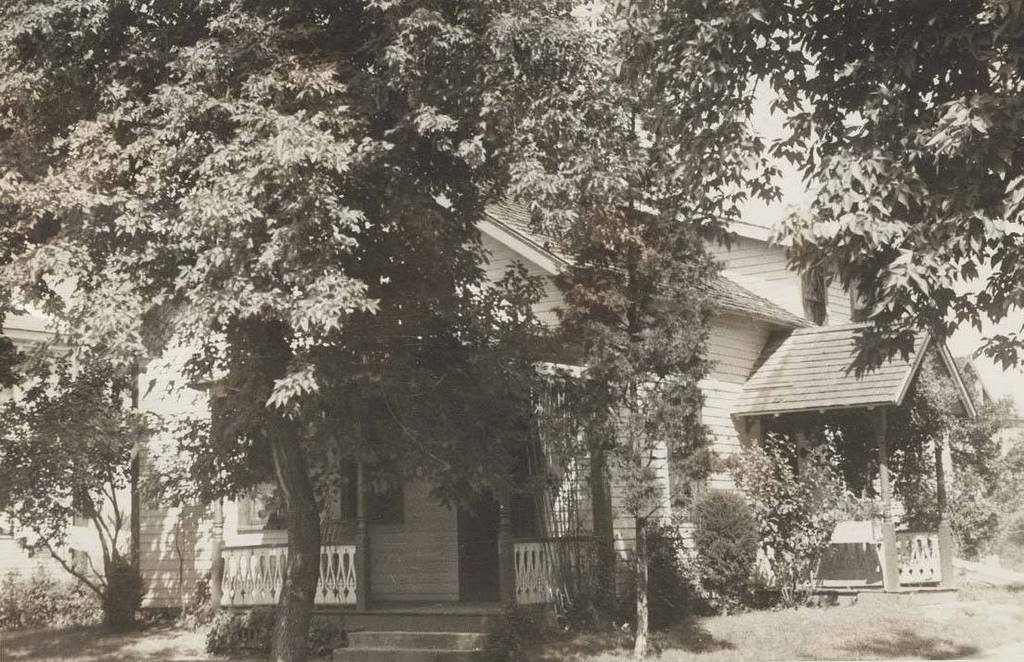

The gravestone of Ephraim Huit at Palisado Cemetery in Windsor, Connecticut, around 1900. Image from Connecticut Magazine, Volume VI.

The scene in 2023:

These two photos show the gravestone of the Reverend Ephraim Huit, who died in 1644. This is generally believed to be the oldest dated gravestone in New England, and it may also be the oldest in the United States. It is located in Palisado Cemetery, which was the colonial-era burying ground for Windsor, the first English settlement in Connecticut.

Ephraim Huit was born in England and was educated at Cambridge. He served as a clergyman in Warwickshire, but he found himself in conflict with the Anglican authorities, apparently because of his nonconformist Puritan views. This may have been what prompted him to emigrate to North America, and he eventually made his way to Windsor, where he was ordained as an assistant pastor of the church in 1639. However, he died only five years later in 1644, when he was about 50 years old.

Among those who had traveled to Windsor with Ephraim Huit were brothers Matthew and Edward Griswold. Both were evidently masons, because Edward is documented as having constructed “the Fort,” a fortified brick house in Springfield, while Matthew was, according to tradition, responsible for carving the gravestone of his in-laws, Henry and Elizabeth Wolcott, here at Palisado Cemetery. Gravestone scholars have likewise attributed several other gravestones to Matthew, including this one here for Ephraim Huit.

The term for this type of grave marker is a box tomb, and it consists of a large flat top that is supported by legs on the corners. In between the legs are four panels, one of which bears the inscription identifying it as the final resting place of Ephraim Huit. Although called a tomb, his body would not have actually been interred in the above-ground space inside it. Rather, his remains would have likely been directly beneath the box tomb.

It is carved of sandstone, which was likely quarried in Windsor. Sandstone was a common material for gravestones in the Connecticut River Valley during 17th and 18th centuries, but it varied in quality depending on its source. Many carvers worked in brown sandstone from the Middletown and Portland area, but this stone tends to be coarse-grained and porous, making the gravestones vulnerable to weathering. Windsor sandstone, on the other hand, tends to have more of an orange-brown color, and it is very fine grained. As a result, gravestones sourced from Windsor have generally survived in much better condition than their Middletown counterparts.

The inscription on the Ephraim Huit stone is carved fairly shallow, but the quality of the material has meant that it is still easily legible nearly four centuries later. Early New England gravestones often have concise inscriptions that give only basic information such as name, age, and date of death. However, this inscription is far more lengthy. It reads:

HEERE LYETH EPHRAIM HVIT SOMETIMES TEACHER

TO Ye CHVRCH OF WINDSOR WHO DYED

SEPTEMBER 4 1644

Who when hee Liued wee drew our vitall Breath

Who when hee Dyed his dying was our death

Who was ye stay of State ye Churches Staff

Alas the times forbides an Epitaph

This last line is particularly puzzling, since it is is an epitaph that says that the “times forbides an Epitaph.” This apparent contradiction is also made more unclear by uncertainty over the meaning of “times.” Did the carver mean it as in there wasn’t enough time to carve a proper epitaph? Or did “times” mean the social, religious, and/or political context of 17th century Connecticut? This latter interpretation seems plausible, since the Puritans generally took a dim view on any kind of elaborate funerary rituals. Could this have been a subversive critique of Puritan society, carved into, of all places, the gravestone of a Puritan pastor?

As for the identity of the carver, there are no surviving records that specifically identify him. It has generally been attributed to Matthew Griswold based on tradition and circumstantial evidence, and it is stylistically similar to several other mid-17th century gravestones that can be found in places such as Hartford, Springfield, and New London. However, it is possible that there may have been another hand involved in making this stone. Matthew’s nephew George Griswold—the son of Matthew’s brother Edward—was also a gravestone carver. His identity as a carver is more firmly established in historical records, and there are dozens of stones that he apparently carved, including many here at Palisado Cemetery.

The bulk of George Griswold’s work dates to the 1670s through 1690s, and his gravestones tended to be small, conventional markers, in contrast to the large box tomb of Ephraim Huit. However, those stones nonetheless show a high degree of skill, leading some scholars to infer that George likely learned from his uncle Matthew. If that was the cause, it seems plausible that he may have assisted in carving the Huit stone. Perhaps the strongest evidence in support of this theory is the lettering on the stone, particularly the letter “y.” On his later gravestones, George Gridswold used a distinctive “y,” with an elongated, curved “tail” that often swooped beneath the preceding letter. Here on this stone, almost every “y” has this feature, with the exception of the one in “LYETH,” which has a standard capital “Y.” This inconsistency might suggest that there may have been more than one carver at work on this stone.

As for the exact date when this stone was carved, it is hard to say. Backdating was a common practice for colonial-era gravestones, with many stones being carved years or even decades after the person’s death. If George Griswold did, in fact, carve some of the letters, then the stone was likely not carved immediately after Huit’s death, since George would have been just 11 years old at the time. But, since the style and lettering is consistent with other mid-17th century stones in the area, it was probably not backdated by much, and was likely carved around the 1650s.

Because backdating was so common during that time period, it is impossible to say with certainty which gravestone is the oldest in New England. There are a handful of others from the 1640s and 1650s, but the Huit stone has the earliest date of any of these. Because of this, and in the absence of any records firmly documenting when a particular stone was carved, the Huit stone seems to have the strongest claim to being the oldest gravestone in the region, and it may also be the oldest dated gravestone in the country. There is a knight’s tombstone in Jamestown, Virginia from 1627, but this stone does not appear to have any dates or other markings.

It would not be until the late 17th century that gravestones would become more common in New England. Early graves may have been marked by wooden markers, or by simple fieldstones, but the idea of permanent, carved monuments was not firmly established in the region until several decades after the Ephraim Huit stone was carved.

Here in Windsor, George Griswold became the first carver in Connecticut to produce gravestones on a large scale. Over the next century and a half, the high-quality sandstone here would continue to draw gravestone carvers to the town, and some of their works can be seen in the background of these two photos. Most visible among these are the three stones directly beyond the Huit stone in this scene. The shortest one, located furthest to the left, marks the grave of John Warham Strong, who died in 1752. His stone was carved by Joseph Johnson, one of the most talented of all the colonial-era carvers in Connecticut.

The two stones on the right, just beyond the Huit stone, were both carved by Ebenezer Drake, another prolific carver in the Windsor area. The stone further to the left marks the grave of Return Strong, who died in 1776, and the one on the right is for his wife Sarah, who died in 1801. The designs of these stones reflect the changes in gravestone carving traditions during those intervening years. When Return died, most gravestones were topped by a winged face that likely represented the soul ascending to heaven. However, by the turn of the 19th century these tastes had shifted to more neoclassical symbols such as willows and urns, as depicted on the top of Sarah’s gravestone.

When Sarah’s gravestone was installed here at the turn of the 19th century, the Ephraim Huit stone was already a relic of a much earlier era. It was also in poor condition, and by the early 19th century it had collapsed. The panel with the inscription was left lying flat and facing up so that it could be read, but the other large panel on the opposite side of the stone evidently disappeared. However, in 1842 it was restored, and a new panel was installed on the other side of the stone, bearing an inscription that commemorated another early Windsor pastor, the Reverend John Warham.

The first photo in this post was taken around 1900, and by this point the gravestone was widely recognized for its historical significance. An 1894 newspaper article described it as “the oldest original monument in the Connecticut valley,” and it also quoted the “quaint inscription” on the stone. In later years, this inscription would also catch the attention of other writers, and it was even featured in a Ripley’s Believe It or Not! newspaper cartoon panel in 1958.

Today, nearly 380 years after the death of Ephraim Huit, his gravestone has remained in good condition. It has seen few noticeable changes since the first photo was taken, although the left side of it does appear to be more weathered and eroded than in 1900. Palisado Cemetery is still an active cemetery, with many modern burials, but the oldest stones are here in the southwestern part of the cemetery. The Huit stone is the oldest of these, but there are many other 17th and 18th century gravestones here in the cemetery, providing many opportunities to study the changing ways in which colonial New Englanders chose to memorialize the dead.