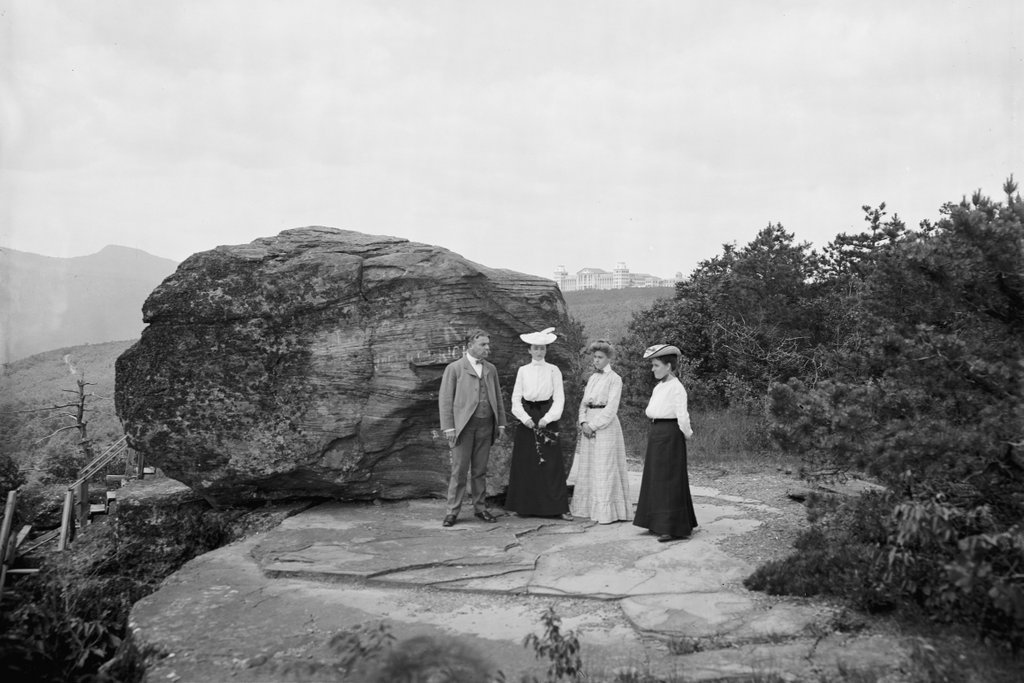

Boulder Rock on the edge of the Catskill Escarpment, around 1900-1902. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2021:

These two photos show Boulder Rock, a large glacial erratic that is perched atop the Catskill Escarpment, at the northeastern edge of Kaaterskill Clove. As with other glacial erratics, the rock was brought here by glaciers during the last ice age, and it was deposited here when the ice melted some 14,000 years ago. It has remained here ever since, despite its seemingly-precarious position at the top of a 1,500-foot drop. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, this area was the epicenter of tourism in the Catskills, with two major resort hotels nearby, and there was a network of trails leading to different points of interest, including this rock. From here, visitors could marvel at the size and position of the rock, while also admiring expansive views to the east and south.

Aside from the rock itself, the first photo also shows the Hotel Kaaterskill, which is visible in the distance near the center of the scene, a little over a half mile away at the summit of South Mountain. This was the second of the two major hotels here, and it opened in 1881 as a competitor to the older, more established Catskill Mountain House. It was built largely out of spite by George Harding, who had visited the Catskill Mountain House in 1880. While there, he had requested a meal of fried chicken for his daughter, but the kitchen refused to cook it because it wasn’t on the menu, and the owner suggested that he open his own hotel if he wanted fried chicken. Harding accepted the challenge, constructing a massive 600-room hotel that, only a few years after it opened, would be expanded to 1,200 rooms. It was larger and newer than the Catskill Mountain House, and it was also higher in elevation, allowing Harding and his guests to literally look down upon the rival hotel.

The caption of the first photo identifies the people here as “Mr. H.E. Eder and family.” Eder, whose first name was Harry, was the manager of the Hotel Kaaterskill. A native of New Jersey, Eder had previously been the manager of the Sierra Madre Villa near Los Angeles, and in 1899 he came to the Catskills as manager of the Haines Falls House. In 1900 he became the manager of the Hotel Kaaterskill, and he appears to have held this position through the 1902 season, although by 1903 he was the manager of the Grand Hotel, located a little to the west of here in the village of Highmount.

As a result, the first photo was likely taken sometime between 1900 and 1902, when he would have been in his mid-40s. He is obviously the person standing furthest to the left in the scene, but the identities of the three women are less certain. His wife Mary was likewise in her mid-40s at the time, and they had one daughter, Marion, who was a teenager. Based on the apparent ages of the women in the photo, Mary is probably the one furthest to the right, with Marion standing next to Harry. The identity of the woman in between them is unclear, although she may have been a cousin or another member of the extended family.

The Hotel Kaaterskill was said to have been the largest mountaintop hotel in the world when it was built, along with being the world’s largest wood-frame hotel. However, the combination of timber framing and isolated mountaintop location contributed to its destruction. On September 8, 1924, about a week after the hotel closed for the season, a fire started in the kitchen. It soon spread throughout the building, and by the time firefighters arrived there was little that they could do to save it. The fire started in the evening and it burned throughout the night, creating a spectacle that could be seen from miles around, reportedly even as far away as Massachusetts.

The hotel was a total loss, and it was never rebuilt. Today, all that remains from the sprawling hotel are the remnants of its foundation, which are mostly overgrown by trees. In the meantime, here at Boulder Rock, not much has changed since the Eder family posed in front of it some 120 years ago. The graffiti on the rock is long gone, and there are more trees here now than at the turn of the 20th century, but otherwise this scene is still easily recognizable from the first photo. Boulder Rock continues to be a noted geological feature here in this area, and it is located along the Escarpment Trail, which runs for more than 20 miles along the eastern edge of the Catskills range.