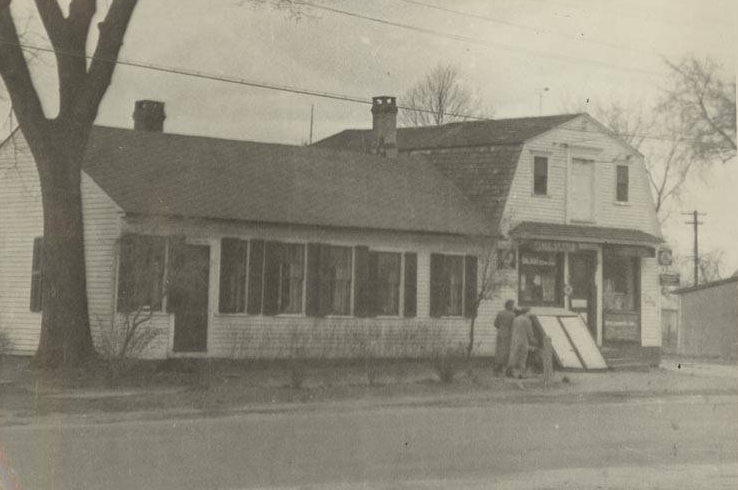

The Ebenezer Grant House on Main Street in South Windsor, Connecticut, around 1934-1937. Image courtesy of the Connecticut State Library.

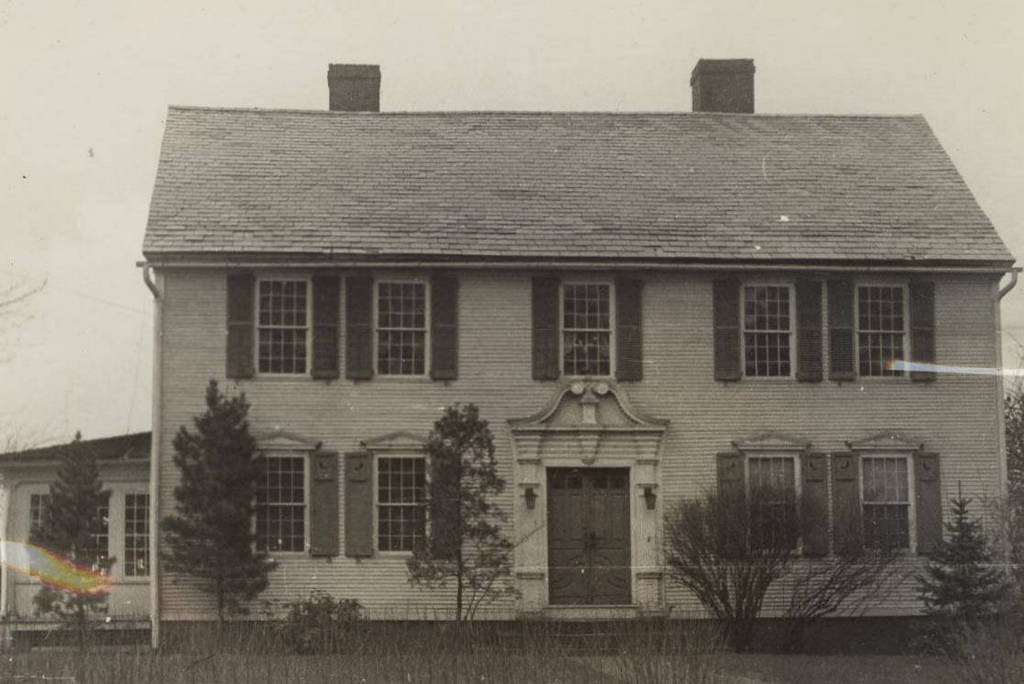

The house in 2022:

The East Windsor Hill neighborhood of South Windsor has many well-preserved 18th and early 19th century homes along Main Street, but perhaps the most celebrated of these is the Ebenezer Grant House, shown here in these two photos. Long recognized as an architectural masterpiece, the house exemplifies the type of homes that were built for the upper class families of the Connecticut River Valley during the mid-18th century.

This house was built around 1757-1758 by Ebenezer Grant (1706-1797), a prosperous merchant who lived in what was, at the time, the eastern part of the town of Windsor. Although located many miles from the ocean, this area is near the head of navigation for oceangoing vessels on the Connecticut River, and Grant was heavily involved in the West Indies trade. He exported commodities such as horses, lumber, tobacco, staves, bricks, and barrel hoops to Barbados and other West Indies ports, and in return imported rum, molasses, sugar, and indigo.

Grant also built several merchant ships here in modern-day South Windsor, near the mouth of the Scantic River, and he was a part owner in many other ships. It does not seem clear as to whether Grant was directly involved in the slave trade, but most of the goods that he imported and exported were closely tied to the plantation economies of the Caribbean colonies.

Aside from trading bulk commodities and other raw materials, Grant also purchased wholesale consumer goods, which he then sold here in his hometown. He had accounts with many of the leading colonial-era merchants in Boston and New York, including John Hancock. Around 1767 he built a store just to the south of his house, and there he sold “dry goods, rum, groceries, hardware, and fancy articles,” according to Henry Reed Stiles in his book History and Genealogies of Ancient Windsor, Connecticut.

Ebenezer Grant’s wealth and social standing were reflected in his house, which was built when he was in his early 50s. Its overall form, with four windows and a door on the ground floor and five windows above them, was typical for houses of the period in this region. But, unlike many of the other mid-18th century houses, it has two chimneys in the main part of the house, rather than a single large chimney in the center. This design choice enabled the house to have a large front entrance hall and staircase, rather than a small entryway with a winding staircase that was typical for the center-chimney homes.

This house is also different from most of its contemporaries in its exterior detail. Most homes of this period were relatively plain on the exterior, but the Grant house included details such as pediments over the first floor windows on the front of the house, and similar pediments over the side doors, which are not visible in these photos. Overall, though, its most famous feature is the highly elaborate front doorway, as shown in these two photos. Often referred to as a “Connecticut Valley doorway,” this style of doorway was perhaps the single most important architectural innovation to be developed in western New England. There were many variations on the design, some with or without the scroll pediment above the door, but the one on the Grant house is among the finest in the region. It is also one of only a handful of scroll pediment doorways that are still on their original houses; many homes were demolished or altered over the years, and several similar doorways are now on display in museums.

As was often the case for 18th century New England homes, the Grant house also included a wing, or an “ell” on the back of the house. These were often added years or decades after the house was built, to accommodate growing families. However, the ell on the Grant house might be even older than the house itself. Some sources, including Stiles’s book, cite a tradition that say the ell was built by Ebenezer Grant’s father Samuel Grant in the late 17th century as a house, and was later moved and incorporated into the new house when it was built in the 1750s. Other sources, though, including the 1900 book Early Connecticut Houses: An Historical and Architectural Study, are skeptical of this theory. It seems more likely that the ell was built at the same time as the main house, perhaps using old timbers that had been repurposed from the previous house.

Ebenezer Grant and his first wife Ann (1712-1783) had six children, although four died young, including three who died within a month and a half of each other in the fall of 1747. By the time they moved into this house in the late 1750s they had two surviving children: a son Roswell (1745-1834) and a daughter Ann (1748-1838). As the only surviving son, Roswell would go on to become a partner in his father’s merchant firm, following his graduation from Yale in 1767. He went on to serve as an officer in the Continental Army during the American Revolution, and after the war he married Flavia Wolcott, whose uncle Oliver Wolcott Sr. had been one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence.

In the meantime, Ebenezer Grant’s wife Ann died in 1783, and a year later he remarried to Jemima Ellsworth. She was the widow of David Ellsworth, and she was also the mother of Oliver Ellsworth, a lawyer who later went on to become a U.S. Senator and Chief Justice of the United States. Jemima died in 1790 at the age of 67, and Ebenezer continued to live here in this house until hos own death in 1797 at the age of 91.

After his death, the house would remain in the Grant family for many years. His grandson Frederick W. Grant later inherited the house, and he lived here throughout most of the 19th century. In his book, Stiles credited Frederick with restoring and preserving the house, which was recognized as an important landmark even as early as the late 19th century. By this point the Grant family had also become famous, due to Ebenezer’s great-great-great nephew Ulysses S. Grant, who was descended from Ebenezer’s older brother Noah.

The top photo was taken sometime around the late 1930s, as part of an effort to document historic homes across Connecticut. By this point the house had seen some alterations, including the addition of an enclosed porch on the left side and the installation of shutters on the windows. Both the porch and shutters were apparently installed around the late 19th or early 20th centuries, since they were not present in a c.1890 photo of the house.

Those changes were later reversed, and today the exterior of the house better reflects its original 18th century design. It stands as an important architectural landmark in the Connecticut River Valley, and it is a contributing property in the East Windsor Hill Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1986.