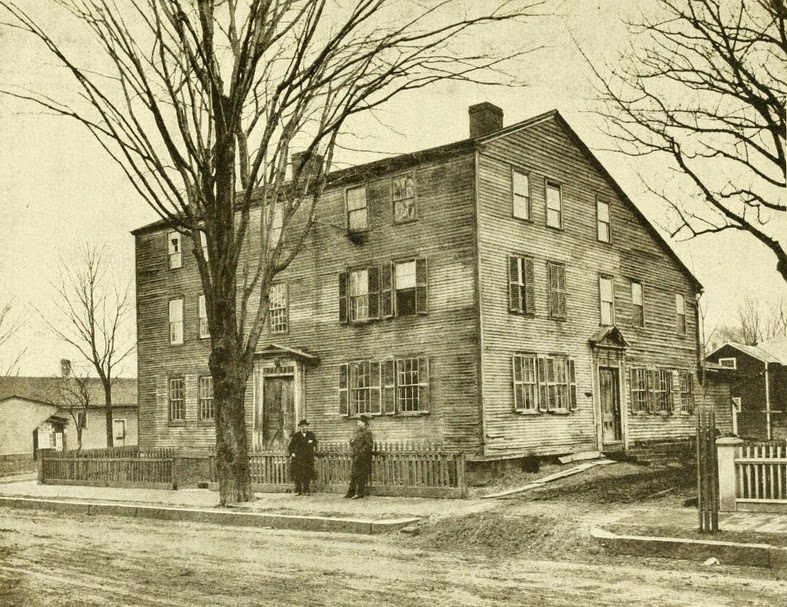

Parsons Tavern on Court Street in Springfield, sometime in the late 1800s. Photo from Our County and Its People: A History of Hampden County, Massachusetts (1902).

The scene in 2023:

When Springfield was settled by European colonists in 1636, it was at a strategic location along several different transportation routes. As the years went by, the modes of transportation changed, but Springfield remained an important crossroads. By the late 1700s, there were three major routes from New York to Boston, the northernmost of which went through Boston. Although a less direct route than the other two, the Springfield route reportedly offered the best taverns, and in Springfield the best was Parsons Tavern.

The tavern was originally built on what is today the southeastern corner of Court Square, and was operated by Zenas Parsons. During its time in operation, it hosted at least two presidents, the first of whom was George Washington in October, 1789. Washington was on his way to Boston, and made a stop in Springfield to inspect the Armory. He stayed overnight at Parsons Tavern, and wrote in his diary that “A Colo. Worthington, Colo. Williams (Adjutant General of the State of Massachusetts), Genl. Shepherd, Mr. Lyman and many other Gentleman sat an hour or two with me in the evening at Parson’s Tavern where I lodged and which is a good House.” Years later, in 1817, President James Monroe also visited the tavern, not long before it was moved in order to make way for Court Square.

The tavern was relocated to Court Street around 1820, and it was eventually divided into a four-family apartment building. The top photo shows it in that location, probably sometime in the late 19th century. It stood here until 1897, when it was demolished. Today, the site of the building is a parking lot adjacent to the G.A.R. Hall, across East Columbus Avenue from Symphony Hall.