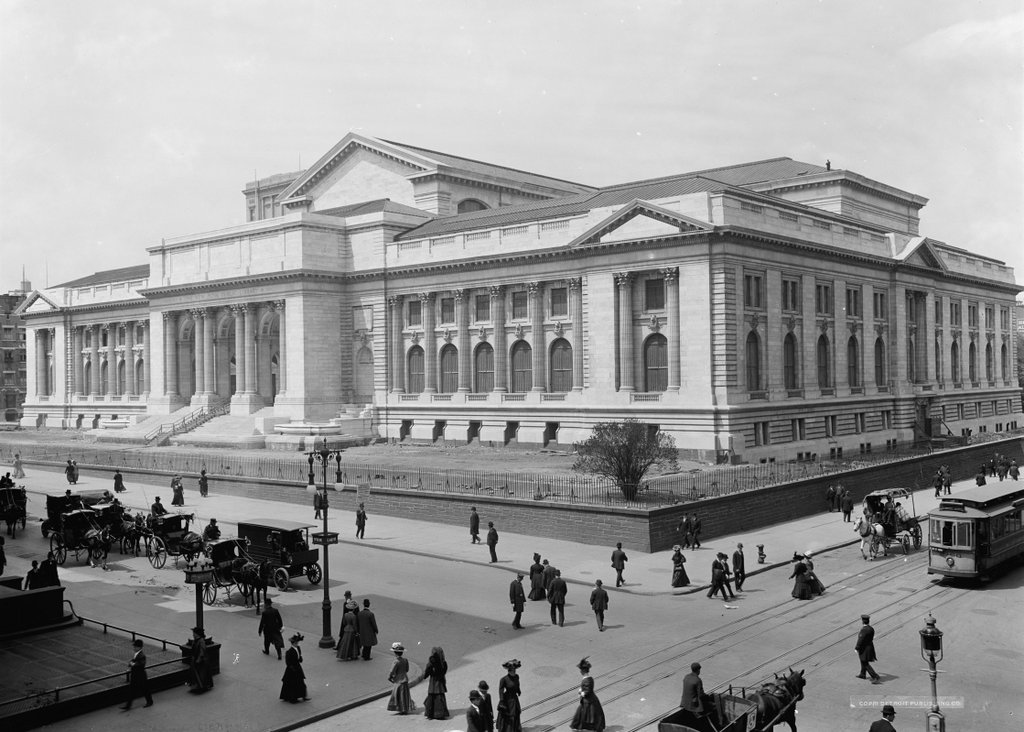

Another view looking north on Fifth Avenue from 51st Street, taken around 1908. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

Fifth Avenue in 2016:

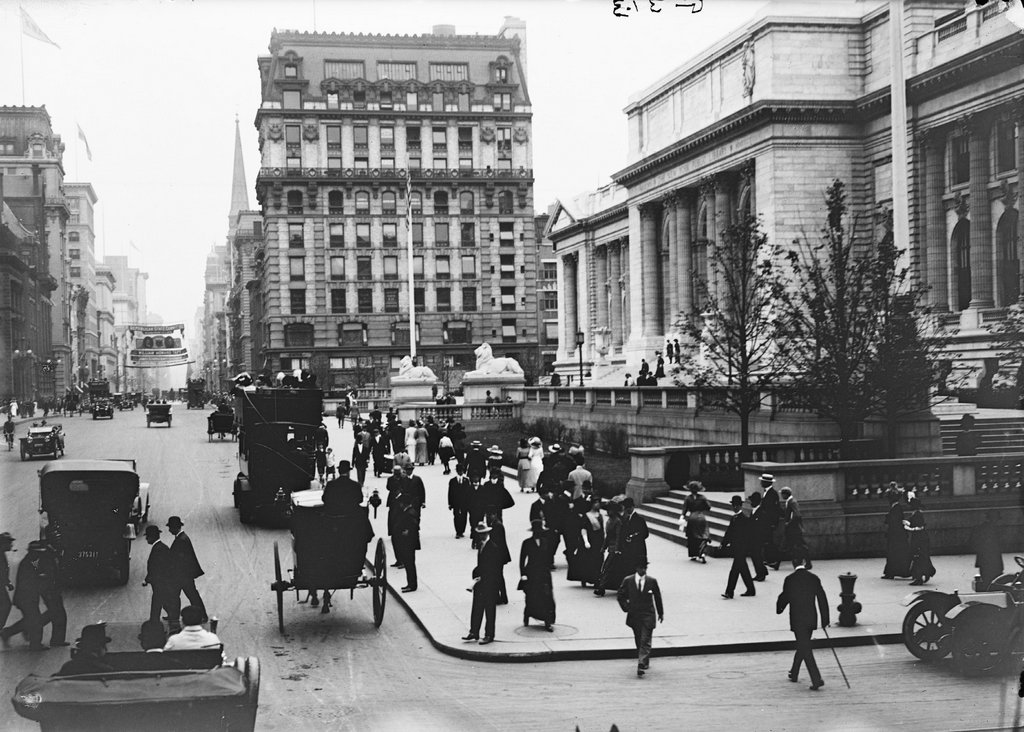

This view is very similar to the one in the previous post, just from a somewhat different angle. Here, it shows not just the Vanderbilt mansions on the left side, but also some of the important buildings to the right. When this photo was taken in 1908, the Gilded Age mansions of the Vanderbilt family were still standing, including the Triple Palace on the far left and William K. Vanderbilt’s Petit Chateau just beyond it. Both of these were built in the early 1880s, but in 1906 a matching house was built right next to the Petit Chateau. It is barely visible from this angle, and hard to distinguish from the original mansion, but it was the home of his son, William K. Vanderbilt II.

The houses on the right side of the first photo were much newer, with the most obvious being the Marble Twins, which have the long second-floor balcony. Completed in 1905, these two townhouses were built for George Washington Vanderbilt II, who is probably best known for his Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina, which is still the largest private home in the country. Just beyond Vanderbilt’s two townhouses here, at the corner of 52nd Street, is the Morton F. Plant House. This was also completed in 1905, for railroad executive and businessman Morton Freeman Plant.

Although this area was home to some of the country’s wealthiest men at the time, the 1908 photo also shows some of the changes that were beginning to take place. In the distance, two large hotels loom over the mansions, reflecting a shift from residential to commercial development on Fifth Avenue. In 1904, John Jacob Astor IV opened the St. Regis Hotel on the right at the corner of 55th Street, and a year later the competing Gotham Hotel was built across from it. They were among the first of what would become a wave of hotels and retailers that would drastically change Fifth Avenue in the coming decades.

Most of the mansions on Vanderbilt Row were gone by the end of the 1920s, including the ones on the left here in this scene. There are a couple of survivors on the right side, although they are mostly hidden from view because of renovations in the 2016 scene. The Plant House is still standing, and is now owned by Cartier, a French jewelry and watch company. Right next to it is one of the two Marble Twins, which is the only remaining Vanderbilt house in the scene. The twin on the right was demolished in 1945, but the one on the left remains, and is now a Versace flagship store.

Today, despite all of the changes, there is a surprising number of buildings still standing from the first photo. Aside from the houses on the right, other buildings include both the Gotham Hotel, which is now The Peninsula New York, and the St. Regis Hotel, which still operates under its original name. Right next to The Peninsula, at the corner of 54th Street, is the University Club of New York, a private social club whose building dates back to 1899. There are also two churches on the left side of the street: Saint Thomas Church closer to the camera, and Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church in the distance, barely visible beyond The Peninsula. The present Saint Thomas Church was built a few years after the first photo was taken, but Fifth Avenue Presbyterian is still standing. It was built in 1875, so it predated the Vanderbilt mansions by a few years and it has outlived most of them by close to a century.