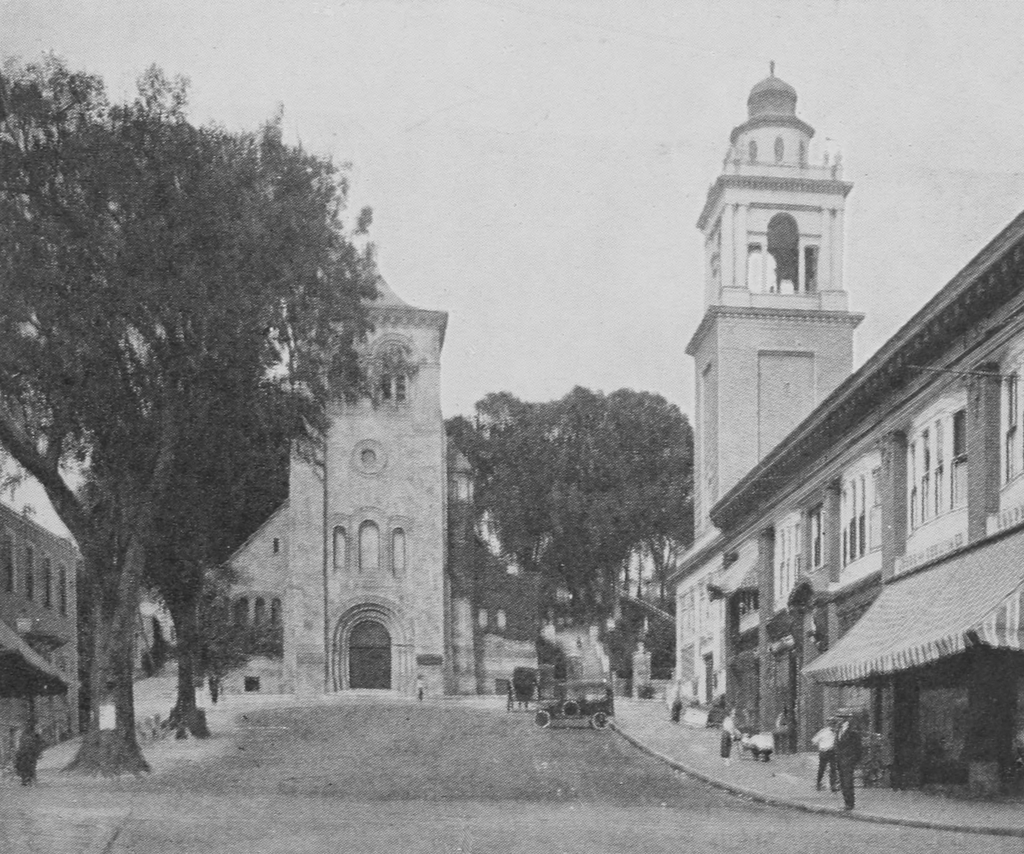

The view looking down the Granite Railway Incline in Quincy, around 1922. Image courtesy of the Thomas Crane Public Library.

The scene in 2021:

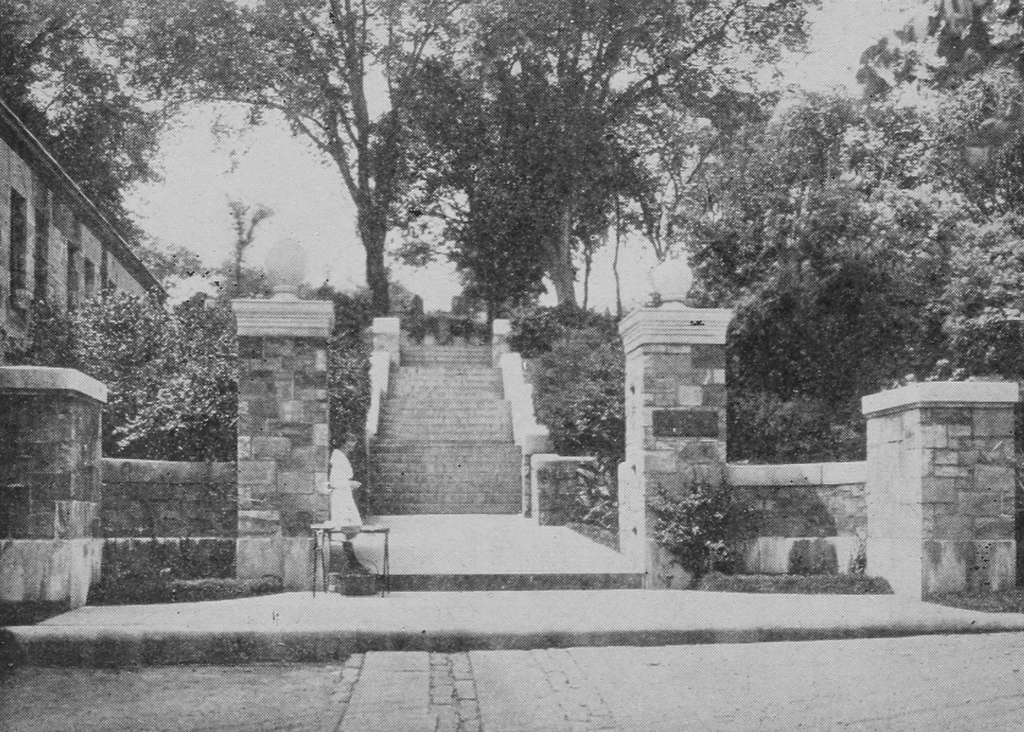

As explained in more detail in the previous post, these two photos show the inclined plane of the Granite Railway in Quincy. Unlike the photos in that post, though, which were taken from the base looking up, these ones show the view looking down from partway up the inclined plane.

The Granite Railway was arguably the first commercial railroad in the United States. It began operations on October 7, 1826, and it consisted of horse-drawn cars that transported granite from the quarries in Quincy to the wharves on the Neponset River. From there, the granite was transported by boat to the Bunker Hill Monument, which was the project that had initially led to the construction of the railway.

The railway was expanded in 1830 with the construction of a small branch that led to the Pine Hill Quarry, located at the top of the hill behind where these photos were taken. To reach the top of the hill, civil engineer Gridley Bryant designed an 315-foot-long inclined plane that rose 84 feet in elevation. It consisted of two parallel tracks, one for empty cars ascending to the quarry and another for cars that were descending with granite blocks. The rails were made of granite topped by iron straps, and the tracks also included a cable that ran on pulleys in the center of the tracks. The cable formed an endless loop, and pulled the empty cars up to the top while also controlling the descent of the loaded cars.

Only two years after it opened, the inclined plane was the site of one of the first fatal railroad accidents in the United States. On July 25, 1832, a group of four visitors was ascending the inclined plane in an empty car when the cable failed near the summit, sending the car plummeting down the tracks. Contemporary accounts estimated that the car reached speeds of around 60 miles per hour before derailing at the base. One occupant was killed, two others were seriously injured, and the fourth walked away with minor injuries.

Aside from this accident, there do not appear to have been any other serious incidents here on the inclined plane, and it remained in use into the 20th century. In 1871, the Granite Railway was acquired by the Old Colony Railroad, which in turn became part of the New York, New Haven and Hartford in 1893. Although it was originally built for horse-drawn trains, most of the old Granite Railway was converted into a conventional railroad, as shown in the distance of the top photo. However, because the inclined plane was too steep for regular trains to use, it remained largely unchanged.

In 1901, new railroad tracks were placed atop the old granite rails, and then in 1920 it was converted for truck use, with metal channels to guide the wheels as the trucks ascended and descended. These are visible on the left side of the top photo, while the track in the center of the photo remained in its original 1830 configuration with the old granite blocks, metal strap rails, and pulleys. Then, in 1921, two obelisks were installed at the base of the incline, to commemorate its role in the early history of railroading.

At some point around the mid-20th century, the upper part of the inclined plane was removed when that part of the hillside was quarried. The landscape was further altered when the Southeast Expressway—modern-day Interstate 93—was built along the former mainline of the old Granite Railway in the 1950s. This did not directly affect the inclined plane, but it dramatically changed the view from this particular spot, as shown in the bottom photo.

The last quarry closed in 1963, and the land eventually became part of the Quincy Quarries State Reservation in 1985. This included the surviving portion of the inclined plane, which remains an important civil engineering landmark. Despite all of the changes over the years, the original granite track has remained well preserved over the years, and it still features the pulleys along with portions of the iron straps that were installed atop the granite rails.