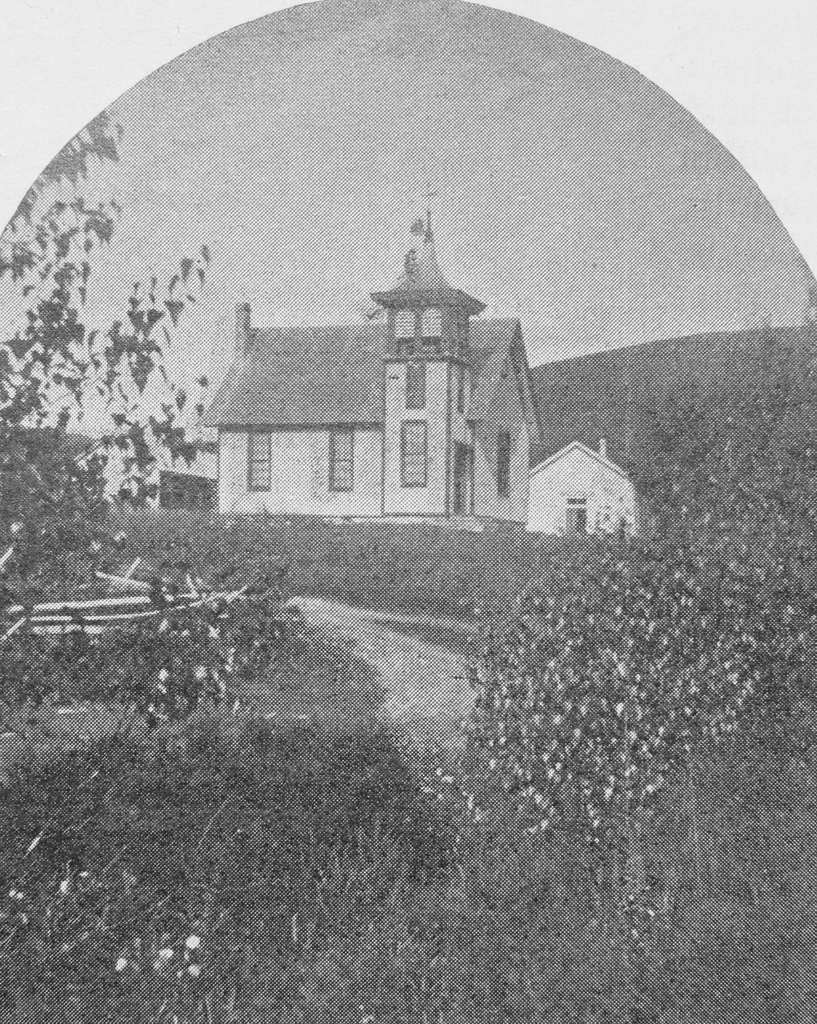

The town center in Ashfield, around 1891. Image from Picturesque Franklin (1891).

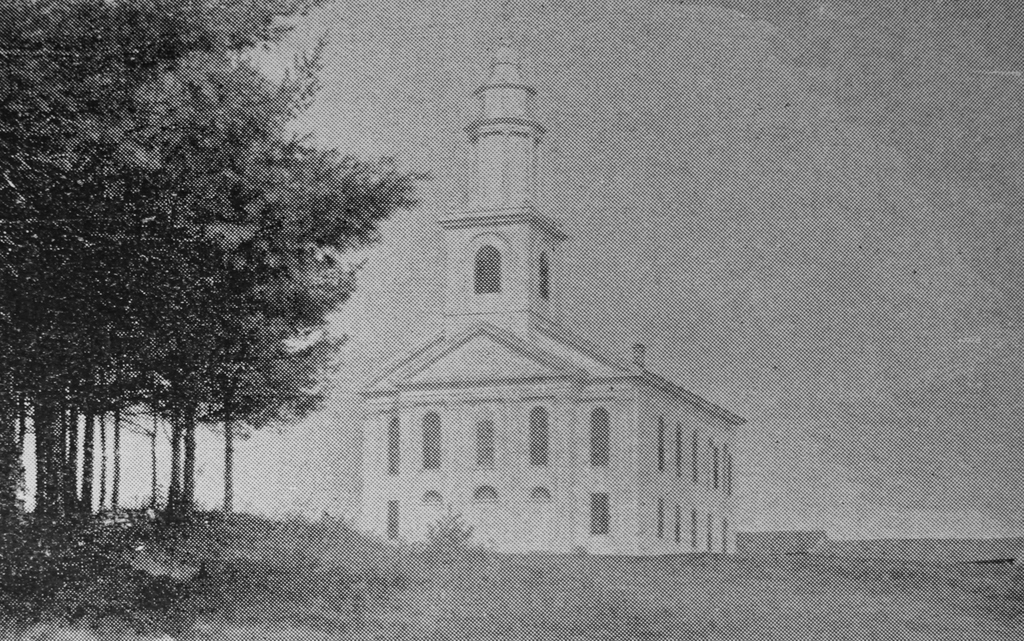

The scene in 2024:

These two photos show the town center of Ashfield, looking east on Main Street from the corner of Norton Hill Road. In the center of both photos is the town hall, which was formerly the congregational church. It is one of the most architecturally significant early 19th century meetinghouses in Western Massachusetts, with a distinctive ornate steeple, as shown in the top photo. The top of this steeple has been temporarily removed for restoration work, which is why it is missing in the bottom photo.

The meetinghouse was originally built about a half mile south of here on Norton Hill Road, adjacent to the Hill Cemetery. Construction began in 1812, with Colonel John Ames of nearby Buckland as the contractor and presumed architect. Ames had built several other churches prior to this one, including ones in Marlborough and Northborough. However, he did not live to see this one completed, because he committed suicide on September 4, 1813. According to the 1910 book History of the Town of Ashfield, Franklin County, Massachusetts, “the contractor, broken in health by hard labor, heavy responsibility and fear of loss, committed suicide by cutting his throat with a chisel in the back part of what is now the cemetery on the hill.”

The building was eventually completed in 1814, and it stood on its original location until 1856, when it was moved down the hill to its current location on Main Street. The church hired a Mr. Tubbs of Springfield to move the building at a cost of $700. However, this ended up being a challenging task, as described in History of the Town of Ashfield:

The contract with Mr. Tubbs was made about April 1st, but as it was a late spring that year the moving could not begin until May 15. As the house was built facing the east it could be started straight ahead. It proved to be a much heavier building than Mr. Tubbs had supposed, and his apparatus broke several times and had to be replaced. At no time could it be moved without raising up the back end so that the whole house would pitch forward. The house was taken straight across the old road south of John Sears’ bam and into the road again at the turn. As anyone can see, it would take a large amount of blocking here to get the house across the hollow, and the moving committee had to hustle around for more. Here Mr. Tubbs struck and said he would go no further with it unless the committee would furnish a team to move the blocking. This, they had not agreed to do but they finally bought a pair of oxen, Mr. Tubbs agreeing to furnish the driver. The oxen were kept in Mr. Moses Cook’s pasture which then came to the road and included what is now Charles Bassett’s mowing lot. In going down the hill it was found necessary to hitch on a big boat load of stone to keep it from going on too fast. When it had arrived at the place where it was to stand, the contractor was going to leave it on the blocking pitched down hill, and the committee had to give him $80 more to put it on the foundation. People now living who saw the moving think the building inclined three or four degrees from the perpendicular, and was very noticeable.

Here at its new location, the building continued to be used as a church until 1870, when the First Congregational and Second Congregational churches merged and moved into a newer church building across the street. The older building was then sold to the town of Ashfield, and it became the town hall. Over the course of the 19th century, the town made a series of improvements and repairs to the building to make it functional as a town hall, including repairing lightning damage after the front of the building was struck in 1897.

Aside from the town hall, there are two other buildings visible in the top photo. Immediately to the right of the town hall is a Greek Revival style home, which was built in the first half of the 19th century. According to the Massachusetts Cultural Resource Information System (MACRIS) documentation for this house, it was the home of the Knowlton family by the 1850s, and was later owned by Archibald Flower. During the early 20th century, the artist William Curtis lived here, and by 1927 it was the Georgianna Inn, which was run by Georgianna Corbett. The house originally did not have a front porch, but one was added around the 1880s or early 1890s, as shown in the top photo.

Closest to the foreground, on the far right side of the scene, is another 19th century building. According to its MACRIS form, it was built around 1835 by Josephus Crafts as a general store. His brother Albert Crafts Sr. later took over the store, followed by Albert’s sons Albert Jr. and William, and it remained in the family for just under a century, until it was sold in 1934. As built, the store was one and a half stories, as shown in the top photo, but around 1894 it was significantly expanded with a full second floor.

Today, more than 130 years after the top photo was taken, all three buildings are still standing, notwithstanding the significant alterations to the store in the foreground. The historic meetinghouse remains in use as the town hall, although it is currently missing the top of its distinctive steeple due to repair work. There have also been some other changes in the area, including the fire station just beyond the town hall, but overall this scene is still very recognizable from the top photo.