The view of the Mount Tom Summit House around 1901-1905. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The same view in 2019:

Rising more than 1,200 feet above sea level, Mount Tom is the highest point on the Metacomet Ridge, a narrow traprock mountain range that extends through Connecticut and Massachusetts from Long Island Sound to just south of the Vermont border. Although modest in elevation compared to the much higher mountains to the west of here in the Berkshires, Mount Tom and the other peaks on the Metacomet Ridge stand out because they are situated in the middle of the Connecticut River valley. As a result, Mount Tom stands nearly a thousand feet higher than the surrounding landscape, making it the most topographically-prominent mountain in the state outside of the Berkshires.

Because of this prominence, the major peaks of the Metacomet Ridge, particularly Mount Tom and nearby Mount Holyoke, became popular destinations starting in the 19th century. This was the era of grand mountaintop resorts, and one of the first in the country was located atop Mount Holyoke, where the view inspired Thomas Cole to paint The Oxbow, one of the most celebrated landscape paintings in the history of American art. The Summit House on Mount Holyoke was soon joined by the rival Eyrie House, which opened in 1861 on Mount Nonotuck, at the northern end of the Mount Tom Range. Together, these two hotels stood watch on opposite sides of the Connecticut River throughout the 19th century.

However, the main peak of Mount Tom, which is located here at the extreme southern end of the mountain, remained undeveloped for many years. Then, in the 1890s, William S. Loomis of the Holyoke Street Railway purchased a large tract of land on the mountain, including the summit, and began developing it into a trolley park for his company. Such parks were common during this period, as the trolley companies benefited not only from admission prices, but also from the increased ridership on weekends, when trolley lines were normally less busy.

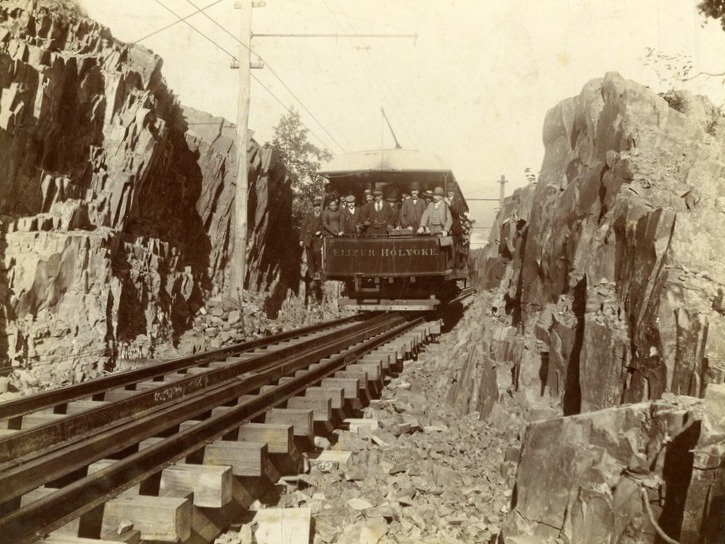

At the base of the mountain, the Holyoke Street Railway built Mountain Park, which featured attractions such as a dance hall, a restaurant, a small roller coaster, and a carousel. These were fairly typical for trolley parks of the era, but a far more ambitious plan involved constructing a funicular railway from the park to the summit. It was known as the Mount Tom Railroad, and it was just under a mile in length, with a total elevation gain of 700 feet. The line featured two trolley cars and one track, with a turnout halfway up the mountain to allow the two cars to pass each other. Both cars were connected via a cable, so that as one car descended, the other ascended. This arrangement significantly reduced the amount of power needed to climb the mountain, as the weight of the descending car helped to pull the other one up.

The railway was completed in 1897, and that same year the first Summit House opened here at the top. It was not a hotel, unlike the older buildings on Mount Holyoke and Mount Nonotuck, but it offered a variety of other amenities for visitors. The first floor featured a restaurant, dining room, and parlors, and the second floor included a stage. On the top of the building was a cupola, with an observatory that was equipped with telescopes. Use of the Summit House was included in the railway fare, which cost 25 cents for a round trip when it first opened.

The Summit House soon proved to be popular, and probably its most distinguished visitor was President William McKinley, who traveled up the mountain with his wife Ida in 1899 and purportedly declared the view to be “the most beautiful mountain out look in the whole world.” The McKinleys’ visit, which included lunch at the Summit House, was well-publicized, and it was even captured on film, in a 30-second clip that still survives today. In the footage, the president and first lady are shown leaving the Summit House and walking along the promenade on the west side of the building, not far from where the first photo in this post was later taken.

Unfortunately, the first Summit House on Mount Tom did not last long. Just three years after its completion, it was destroyed by a fire on October 8, 1900. The cause of the blaze was never determined, although it apparently started in the basement, where the watchman discovered it around 8:45 p.m. Some of the contents were rescued from the burning building, but otherwise it was a total loss. The fire proved to be quite a spectacle for the surrounding area, and it was reportedly visible from at least 20 miles away. The Springfield Republican, reporting on it the following day, dramatically described how “From one end of the valley to the other, north and south, men’s eyes were turned to the beacon of flame in wonder, in pity, and in admiration.” Further in its narrative, the newspaper declared that “The sight of such a titanic bonfire will not soon be forgotten by those who witnessed it.”

Mountaintop buildings were particularly vulnerable to fires. Not only were they generally built of wood, but they were also located far from water sources, making firefighting a challenge. Just six months later, in April 1901, the nearby Eyrie House on Mount Nonotuck suffered the same fate as the first Summit House. In that case, the fire began after the owner, William Street, cremated two horses that had died at the top of the mountain. After the cremation, Street believed that the fire was out, but it reignited during the night, destroying the old hotel and the other buildings at the summit. The Eyrie House was never rebuilt, and its ruins still stand at the top of the mountain.

Here at the Summit House, though, the owners moved quickly to construct a new building. The second Summit House, which is shown here in the first photo, was completed in 1901, and it was significantly larger than the original one. The dining room was located on the first floor, with a hall and stage on the second floor. Both of these floors also had 14-foot-wide piazzas that extended around the entire building. The third floor featured another hall, along with storerooms and water tanks, and it was surrounded by an open deck above the piazzas.

The main observatory, with its large plate glass windows, was on the fourth floor, but there were three more levels of observatories that rose above it. The highest level was the cupola, which measured 11 feet in diameter and stood nearly a hundred feet above the ground. It was equipped with telescopes, and it was topped by an octagonal copper dome that was covered in gold leaf. Overall, the Summit House cost about $25,000 to build, and it was designed by local architect James A. Clough, who was responsible for a number of important buildings in Holyoke at the turn of the 20th century.

The first photo was taken within a few years after the new Summit house was completed, and it shows the northwest corner of the building. On the right is the boardwalk that, only a few years earlier, President McKinley had walked on. Just beyond the railing is the steep western cliff of the mountain, and from here visitors could enjoy panoramic views of Easthampton and the surrounding landscape, with the Berkshire mountains further to the west. The east side of the mountain, which is partially seen on the left side of the photo, slopes down more gently, but it still afforded views to the south and east, facing toward the cities of Holyoke and Springfield. In the foreground, in the center of the photo, is a small kiosk. It appears to have been closed at the time, but in other photos of the summit it has a sign advertising for salted peanuts and corn cakes, which could be had for five cents.

With the new Summit House completed, visitors continued to make the trip up the mountain in large numbers. In 1903, the Springfield Republican reported that around 60,000 to 80,000 people came here each year, during the nearly six-month operating season. Up to that point, the single-day record was 3,300 people, which occurred on a Labor Day. Around 1904, one of the visitors to the mountaintop was a young Calvin Coolidge, who came up here with his future wife, Grace Goodhue, early in their courtship. He purchased a porcelain plaque of the mountain here, and this became the first gift that he ever gave to her.

Throughout the first quarter of the 20th century, the Summit House remained a popular attraction. The number of visitors remained fairly constant during this time, with an average of about 75,000 in its later years, and 80,000 in its last full season of operation in 1928. However, like its predecessor, this Summit House was also destroyed in a fire. The night watchman discovered the fire on the observation floor around 6:00 p.m. on the night of May 2, 1929. After alerting the fire department he attempted to extinguish the flames himself, but he was unsuccessful. By the time the firefighters arrived, there was little that could be done to save the building. These efforts were hampered, at least in part, by the fact that the hotel’s 5,000-gallon water tanks were not working properly.

As with the burning of the first Summit House, this blaze attracted considerable attention in the vicinity of the mountain, and it was visible from at least 30 miles away. The Holyoke Street Railway, which still owned the property, even capitalized on the public’s morbid curiosity, and within a matter of days they were bringing sightseers up here on the trolleys to view the remains of the Summit House, which consisted of little more than the stone foundation and the chimney.

In the meantime, the Holyoke Street Railway wasted no time in building a temporary replacement. This hastily-constructed Summit House opened less than two months later at the end of June, and it consisted of two stories, with a steel frame and corrugated steel walls. It was much smaller than either of its two predecessors, with dancing and dining facilities relocating to Mountain Park, but the new building did offer refreshments and souvenirs, along with telescopes for visitors to use. It was located immediately to the north of the old building, around the spot where these two photos were taken.

Although designed to be temporary, this third building was never replaced by a permanent structure. Mountaintop resorts such as the Summit House were already in decline by the late 1920s, thanks to the increasing popularity of automobiles and the new travel opportunities that they created. The Great Depression, which began just months after the grand reopening, did not help matters either, and by the end of the 1930s both the Mount Tom Railroad and the Summit House had closed.

The railroad tracks were taken up in 1938 or early 1939, and the temporary summit house was dismantled around the same time. The steel beams were sold for scrap, but the corrugated steel panels were unceremoniously dumped over the side of the cliff, where they still remain more than 80 years later. Only the upper railroad station, which was just a little further to the north of here, was left standing, but this burned in 1941.

The Holyoke Street Railway continued to operate Mountain Park at the base of the mountain, and the park survived into the late 1980s. However, in 1944 the company sold the summit area to the WHYN radio station. Using the mountain’s elevation to increase its range, WHYN built towers and transmitter buildings here in the foundation of the old Summit House. The old railroad bed was converted into a paved access road, and the project was completed in 1947, when WHYN and two other local stations, WACE and WMAS, began broadcasting from here.

Today, more than a century after the first photo was taken, the summit continues to be used by a variety of radio and television stations. The old Summit House foundation is still there, although it is off-limits to the public and guarded by a barbed wire fence. However, the rest of the summit area is open for hikers, who are able to enjoy the same views that drew tens of thousands of visitors here each year during the early 20th century. And, although much has changed here, there are still some reminders of what used to be here. Most obvious is the boardwalk, which still runs along the western cliff of the summit. Much of it has collapsed, especially here in the foreground, but it stands today as the only surviving feature from the first photo.