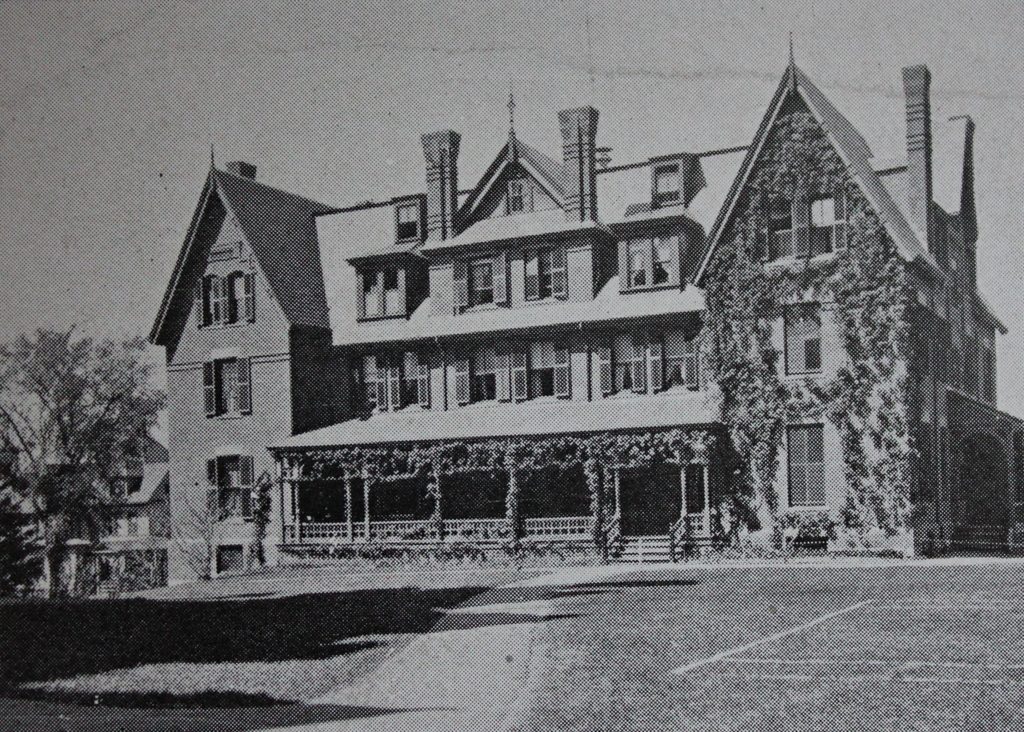

Lawrence House on the campus of Smith College in Northampton, around 1894. Image from Northampton: The Meadow City (1894).

Lawrence House in 2018:

When Smith College opened in the fall of 1875, there were just 14 students enrolled in the school. However, over the next few decades the school saw dramatic growth, resulting in a number of new buildings on campus in the 1880s and 1890s. In the six year period from 1886 to 1892, for example, enrollment grew from 247 to 636, and in 1892 two new dormitories were added to accommodate this influx. The two identical buildings, Lawrence House and Morris House, were both designed by William C. Brocklesby, a Hartford architect who was responsible for many of the campus buildings during this period, and they were named in honor of two Smith College alumnae: Elizabeth Crocker Lawrence, class of 1883; and Kate Morris, class of 1879.

Lawrence House, seen here in these two photos, became a cooperative house in 1912, with students receiving discounted tuition in exchange for doing one hour of chores each day. The 62 spots here were highly competitive, requiring high academic standing as well as an interview with the dean, and former resident Constance Jackson, writing for The Smith Alumnae Quarterly in 1922, noted that “it is considered a stroke of luck by most of the college to achieve Lawrence House.” At the beginning of the school year, students were assigned temporary jobs, but they later submitted their preferences for permanent jobs. As Jackson described in her article:

Later, when academic schedules are definitely settled, each student gives the head of the house a card bearing her first, second, and third choice for a permanent task, as well as her “pet aversion.” Needless to say these are never assigned! The freshmen are but little concerned for they have already been informed by upper classmen who have achieved the dignity of sweeping and setting up tables, that the dinner dishes constitute their particular destiny.

Jackson went on to explain how:

The work is never a burden in any sense, for the hour each day spent at one’s particular task is a wholesome change from the academic atmosphere. The interest which everyone takes in the well-being of the house as a whole is truly remarkable and far different from the attitude commonly seen in the houses where the duties of keeping up appearances fall to maids. A scrap of paper in the hallway, a bit of dust on the stairs, is noticed and immediately removed by whomever sees it first – not because it is a duty but because it reflects on the common home which we have all come to love.

Lawrence House remained a cooperative house for many years, and during this time its most famous resident was Sylvia Plath, who lived here from the fall of 1952 until her graduation in the spring of 1955. Although best known for her 1963 novel The Bell Jar, Plath has already written many short stories by the time she moved into Lawrence House, and several of these had been published in magazines. While at Smith College she also served on the editorial board of the school’s literary magazine, the Smith Review, and in 1953 she was selected as a guest editor for Mademoiselle. However, her college years were also marked by increased depression, and her time at Lawrence House was interrupted in 1953, when she spent six months in a psychiatric hospital after her first suicide attempt.

Today, Lawrence House is no longer a cooperative house, but it remains in use as one of 35 residential buildings on the Smith College campus, housing 68 students. The exterior has seen few changes, although at some point in the mid-20th century the dormer windows on the long sides of the building (not visible from this angle) were significantly altered. Otherwise, both Lawrence House and its twin, Morris House, remain very much the same as they did when they were completed over 125 years ago.