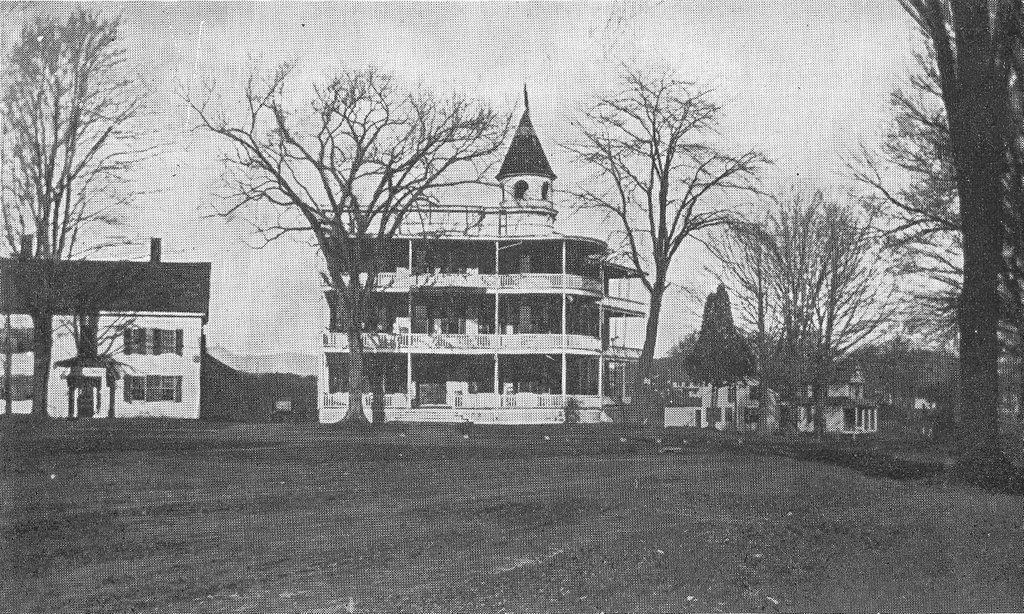

The Executive Mansion on Eagle Street in Albany, around 1900-1906. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2019:

This house underwent several different transformations during the 19th century, but the original structure was built in 1856 as the home of businessman Thomas Olcott, the longtime president of Mechanics and Farmers Bank. At the time, it was a comparatively modest Italianate-style house, but it was extensively remodeled in the 1860s by its second owner, Robert L. Johnson. He added Second Empire-style details to the exterior, including a Mansard roof, bay windows, and a tower on one corner.

In 1875, toward the end of Johnson’s ownership, the house was rented by Governor Samuel J. Tilden, who worked a half mile away from here at the old state capitol. Tilden served as governor for two years, from 1875 to 1876, and he was also the Democratic nominee for president in the highly controversial 1876 election. Tilden won the popular vote, but the results from four states were contested. All of these states were ultimately awarded to his Republican challenger, Rutherford B. Hayes, giving him 185 electoral votes to Tilden’s 184. To this day, Tilden remains the only presidential candidate to lose despite receiving an outright majority of the popular vote.

Tilden retired from politics after the election, and his successor here in Albany was Lucius Robinson. In 1877, during Robinson’s time as governor, the state purchased this house from Johnson and established it as the official residence of the governor. Then, in the mid-1880s, the state hired architect Isaac G. Perry to renovate the house. At the time, Perry was also supervising the construction of the new capitol, and his work here at the Executive Mansion involved an expansion of the house and a complete redesign of the exterior. The project was finished around 1887, giving the house a Queen Anne-style design that rendered it nearly unrecognizable from its previous appearances. The first photo, which was taken around the turn of the century, shows the exterior view of the house after this remodeling.

In the meantime, the house was occupied by several other notable governors during the late 19th century. From 1883 to 1884, just prior to Perry’s renovations, it was the home of Grover Cleveland. Like Tilden, he also ran for president while serving as governor, and he received the Democratic nomination in 1884. He proved more successful in the general election, though, defeating James G. Blaine to become president. Cleveland lost the following election in 1888 to Benjamin Harrison, but he won again in 1892 and served for another four years. In the process, he became the only president to serve non-consecutive terms, and he was also the only Democrat to be elected president in the half-century span between James Buchanan and Woodrow Wilson.

From 1895 to 1896, the executive mansion was occupied by Levi P. Morton, who had previously served as vice president under Benjamin Harrison. He was dropped from the ticket for Harrison’s unsuccessful bid for re-election in 1892, but this apparently did not hurt his political career, because he was elected governor of New York two years later. As a result, he is the only former vice president to hold a statewide elected office after the end of his vice presidency.

Morton was the first in a line of six consecutive Republican governors who were elected in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Among these, the most famous was Theodore Roosevelt, who served from 1899 to 1900. A native of New York City, Roosevelt had previously been to Albany as a state legislator in the early 1880s. He left politics soon after the death of his first wife Alice in 1884, and he went on to have a successful career as a writer, with most of his books focusing on either American history or hunting.

Roosevelt would continue writing for the rest of his life, but did not stay out of politics for very long. He ran unsuccessfully for mayor of New York in 1886, where he finished a distant third in the general election, but he was subsequently appointed to the United States Civil Service Commission. From 1895 to 1897 he served as president of the New York City Board of Police Commissioners, and then he spent a year as Assistant Secretary of the Navy before resigning to join the famous Rough Riders regiment during the Spanish-American War.

Returning to New York as a war hero, Roosevelt easily received the Republican nomination for governor in 1898. He defeated Democrat Augustus Van Wyck in the general election, and began his term as governor on January 1, 1899. When he had last held elected office here in Albany 14 years earlier, he had been a 26-year-old widower with an infant daughter. Now, at the age of 40, he was remarried to his second wife Edith, and they had five more children, the youngest of whom was just a year old.

On his first night as governor, Roosevelt stayed out too late, and when he finally returned to the Executive Mansion he found that the servants, assuming he was already in bed, had locked the doors. Rather than awaken his family, he decided to break into the house by climbing through a window. Many years later, Roosevelt biographer Edmund Morris would use this incident as a way of foreshadowing the disruptive effect that the new governor would have on state politics, particularly in his clashes with Thomas C. Platt, a state senator and boss of the state’s Republican Party.

As it turned out, Roosevelt’s political opponents here in New York would inadvertently advance his career, and less than three years after crawling through the window here in Albany he would find himself living in the White House. Resolving to rid New York of the controversial Roosevelt, Senator Platt had suggested him as William McKinley’s vice presidential candidate for the 1900 election. At the time, it did not seem to be a particularly risky move; no former vice president had gone on to be elected president since Martin Van Buren in 1836, and Platt hoped that Roosevelt would fade into political obscurity just as almost every other vice president had done.

The McKinley-Roosevelt ticket went on to an easy victory against Democrat William Jennings Bryan, and Roosevelt was sworn in as vice president on March 4, 1901, just two months after his term as governor ended. Unfortunately for Platt and his wing of the Republican Party, McKinley was shot by an assassin on September 6, 1901, and died a week later. Roosevelt then assumed the presidency, and was subsequently elected to a second term in 1904.

After Roosevelt, the next New York governor to run for president was Charles Evans Hughes, a New York City attorney who served as governor here in Albany from 1907 to 1910. He resigned near the end of his second term when William Howard Taft appointed him to the United States Supreme Court, and Hughes served as an associate justice until 1916, when he resigned after receiving the Republican nomination for president. However, he lost the election to incumbent Woodrow Wilson, whose razor-thin margin of less than 4,000 votes in California determined the election. The loss cost Hughes his lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court, but he continued to have a successful political career, serving as Secretary of State in the Harding and Coolidge administrations before being reappointed to the Supreme Court in 1930, this time as chief justice.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, serving as governor of New York continued to be a major stepping stone to the presidency. In 19 presidential elections between 1876 and 1948, 13 of them featured a sitting or former New York governor at the head of at least one of the major party tickets. After Hughes’s loss in 1916, the next was Al Smith, who was governor from 1919 to 1920, and 1923-1928. He challenged Herbert Hoover in the 1928 election, but lost in a landslide, failing to even win his home state.

Smith’s successor as governor, who was also the next Democratic candidate for president, was somewhat more successful in presidential elections. Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had previously run for vice president in 1920, served as governor here for four years, from 1929 to 1932. During this time, the Executive Mansion underwent some modifications to accommodate his disability, including the installation of wheelchair ramps and an elevator. In addition, the greenhouse was transformed into a pool, as Roosevelt believed that the therapeutic value of swimming in hot water would improve his condition.

Roosevelt’s first term as governor coincided with the start of the Great Depression, and he became a leading supporter of progressive policies at the federal level. His re-election in 1930 established him as a major presidential contender, although as the 1932 Democratic convention approached he faced opposition from here in his home state. Al Smith, a more conservative Democrat, hoped to block Roosevelt and gain the nomination instead, but the convention ultimately choose Roosevelt, who went on to win all but six states in the general election, defeating a very unpopular Herbert Hoover.

Roosevelt would go on to win an unprecedented four presidential elections, serving throughout the rest of the Great Depression and almost all of World War II. None of these elections were particularly close, but his most successful challenger, in terms of both the popular and electoral votes, was a fellow governor of New York, Thomas Dewey. He had been elected governor in 1942, becoming the first Republican to win the office since Nathan L. Miller in 1920, and two years later he ran against Roosevelt, receiving 99 electoral votes and nearly 46% of the popular vote.

Dewey was the Republican nominee again in 1948, when the Chicago Tribune famously but erroneously declared that he defeated Truman. Although most experts projected that he would win the election, he ended up earning a lower percentage of the popular vote than he had in 1944, and carried just 16 states. However, these two presidential losses did not hurt his career here in Albany, and he served as governor until 1954. His 12 years as governor were, at the time, the longest in the state’s history since George Clinton served 18 years from 1777 to 1795.

Since Dewey, no other New York governors have been nominated for president. However, several of his successors have gained national prominence, perhaps most notably Nelson Rockefeller. He was the grandson of oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller, and he was first elected governor in 1958. He would go on to be re-elected three more times, surpassing the length of Dewey’s tenure, and he still remains the state’s longest-serving governor since Clinton. Rockefeller served here in Albany until 1973, when he resigned to join the Commission on Critical Choices for Americans. A year later, he was appointed vice president under Gerald Ford, after Ford assumed the presidency in the wake of Nixon’s resignation. He went on to serve as vice president until the end of Ford’s term in 1977.

During Rockefeller’s many years as governor here, the capitol area underwent a dramatic transformation. Most notably, this involved the construction of Empire State Plaza, a massive complex of government buildings that extends westward from the Capitol to the rear of the Executive Mansion. The mansion itself also saw changes during this time. In 1961, only two years into his time as governor, the mansion was heavily damaged by a fire. Some called for it to be demolished or for the state to purchase a new house elsewhere in the city, but Rockefeller preferred to preserve the fire-damaged building, and it was subsequently restored and, in 1971, added to the National Register of Historic Places.

In recent years, not all of New York’s governors have spent much time actually living here in the Executive Mansion, but it remains the state’s official residence of the governor. Today, the trees in the foreground hide most of the house from this angle, and the grounds now have much more security than when the first photo was taken at the turn of the 20th century. However, the exterior appearance of the house still looks much the same as it did back then, and it stands as one of the most important historic buildings in Albany, due to its association with so many of the most influential American politicians of the late 19th and 20th centuries.