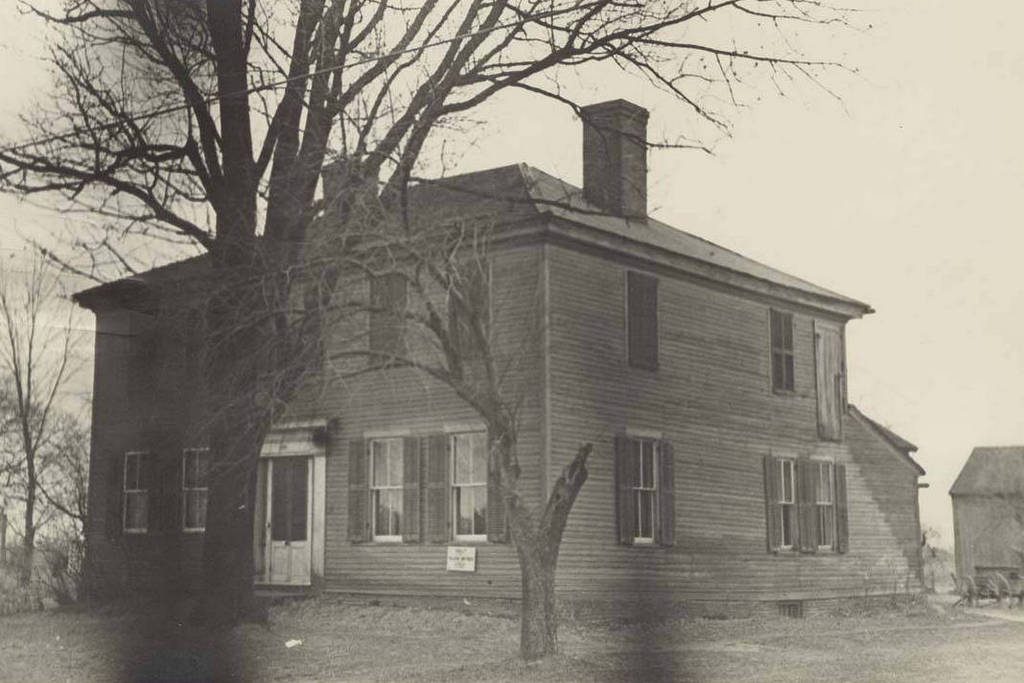

The house at 336 Palisado Avenue in Windsor, in August 1938. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Historic American Buildings Survey Collection.

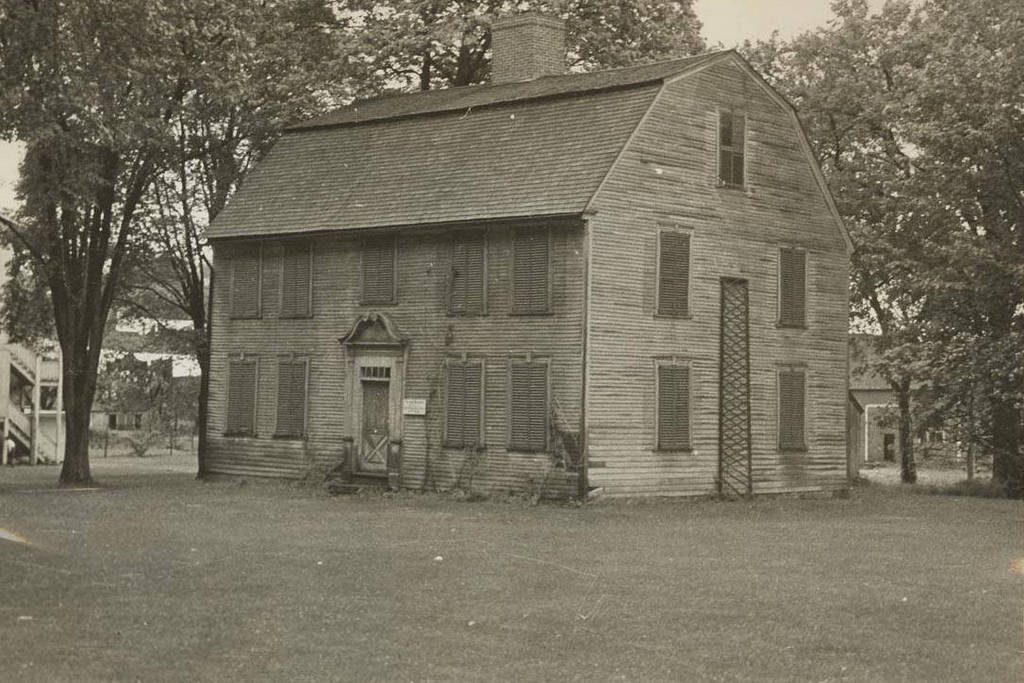

The house in 2017:

This house is one of the finest Georgian homes in Windsor, and was built in 1784 for Jonathan Ellsworth. They were a prominent family in 18th century Windsor, and one of his relatives was Oliver Ellsworth, the third Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court, who lived a little further north of here on Palisado Avenue. Jonathan Ellsworth’s house would remain in his family for many years, and by the mid-19th century it was owned by William H. Ellsworth, who lived here with his wife Emily and their four children: William, Horace, Elizabeth, and Clara. Horace would later inherit the house, and owned it until his death in 1934, exactly 150 years after the house was built.

The first photo was taken only four years after Horace’s death, and it shows the alterations that had happened to the house over the years. It had lost many of its original Georgian details, and the WPA architectural survey, which was completed around the same time, noted that it was only in “fair” condition. However, in the 1960s it was restored to its former grandeur, with features such as historically appropriate windows, the scroll pediment over the door, the lintels over the first floor windows, and the quoins on the corners of the house. It is an excellent surviving example of an 18th century home in Windsor, and it is a contributing property in the Palisado Avenue Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places.