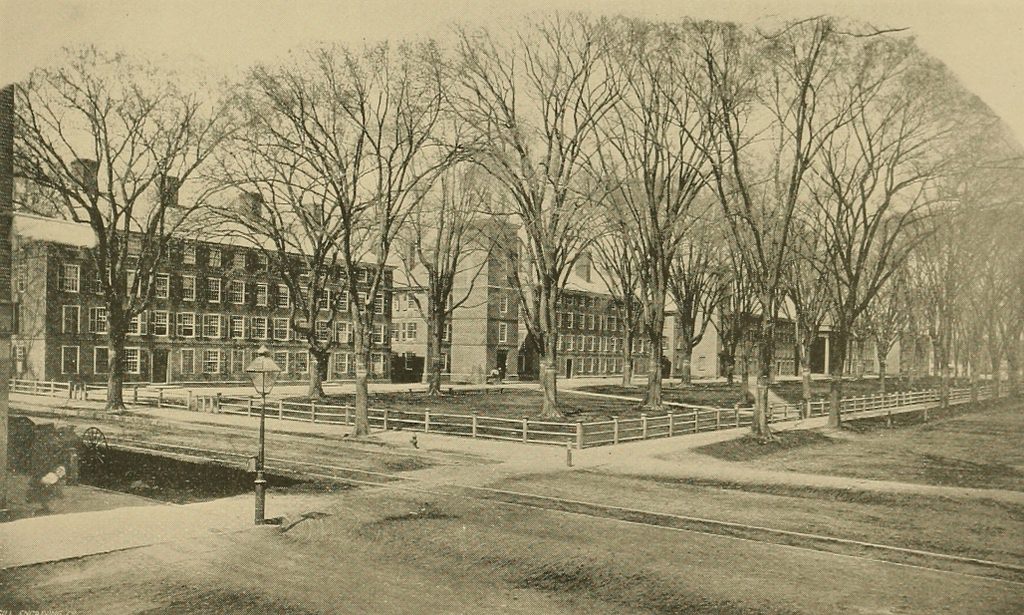

Center Church and United Church, as seen looking west on the New Haven Green, around 1900-1915. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2018:

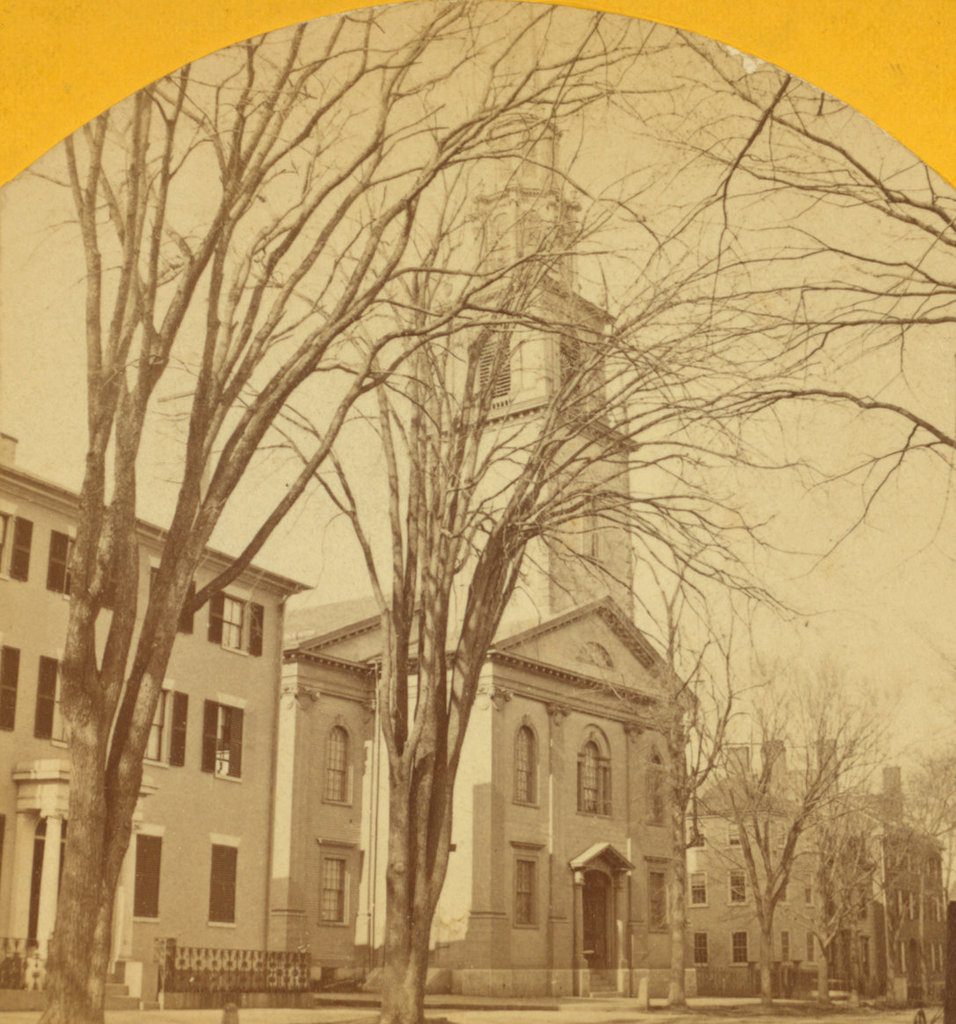

This view shows two of the three historic churches that were built on the New Haven Green in the 1810s. The oldest of these, on the left side of the scene, is Center Church, which was completed in 1814. It was built of brick, and featured a Federal-style that was designed by Asher Benjamin and Ithiel Town, two Connecticut-born architects who were among the leading American architects of the early 19th century. Like many New England churches of this period, it featured a columned portico, along with a tall, multi-stage steeple that rose above it.

Although not readily apparent in this view, one of the more unusual features of Center Church is its basement. Throughout the colonial era, this section of the Green served as New Haven’s burial ground, and an estimated 4,000 to 5,000 bodies were interred here. Center Church was built in the midst of this cemetery, but rather than removing the remains or the headstones, the church was simply built above them. The ground became the floor of the basement, but otherwise the graves were not disturbed, and the headstones are still well-preserved today. However, this was only a small portion of the entire cemetery. The rest of the headstones, which are once located around the outside of the church, were moved to Grove Street Cemetery in 1821. The remains themselves were not disinterred, though, and they are still buried here under the Green.

In the meantime, Center Church was joined by two other churches in the mid-1810s. To the right of it, at the corner of Temple and Elm Streets, is the United Church, which was completed in 1815. It was, along with the neighboring Center Church, a Congregationalist church, and it likewise had very similar architecture. There is some disagreement among historic sources over who the architect was, but it appears to have been Ebenezer Johnson, Jr. His design was likely influenced by Center Church, but the United Church does have some differences, such as a lack of a portico, and it featured a shorter steeple with a rounded top, instead of a tall pointed spire.

The third church to be built here on the Green was Trinity Church, completes a year after United Church in 1816. Although not visible in these photos, it featured Gothic-style architecture that sharply contrasted with its Federal-style neighbors, and was one of the first Gothic churches to be built in the country. Today, all three of these church buildings are still here, and they are all contributing properties in the New Haven Green Historic District, which was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1970. Overall, very little has changed in this scene, and even many of the buildings in the distance have remained. These include another historic church, the First and Summerfield United Methodist Church, which can be seen in the background just beyond and to the left of the United Church. It was built in 1849, with a design similar to these other two churches, and it still stands at the corner of Elm and College Streets.