The House of Representatives chamber in the Vermont State House, around 1865-1875. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The scene in 2019:

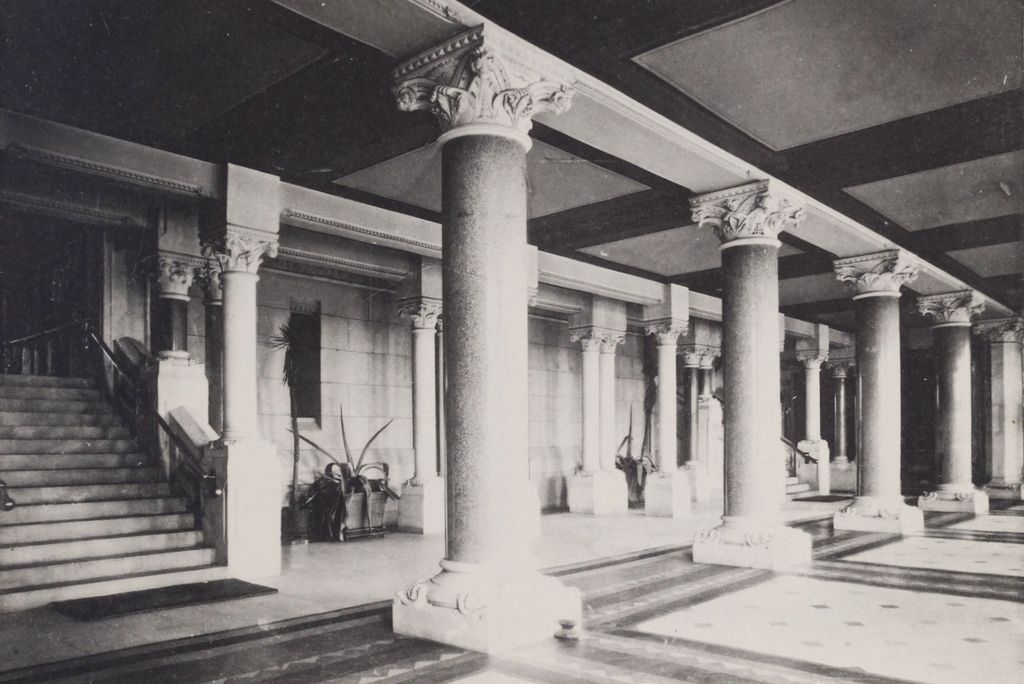

The current Vermont State House opened in 1859, replacing an earlier building on the same site that had been gutted by a fire in 1857. The layout of the building consists of two floors, with most of the major government functions here on the second floor. The east wing of the building houses the Senate chamber, and the ceremonial governor’s office is on the opposite side of the building in the west wing. In the center of the building, located beneath the dome, is the House of Representatives chamber, which is shown in this scene looking down the central aisle toward the rostrum.

This building was used for the first time during the October 1859 session of the state legislature. Shortly after it opened, the Vermont Watchman & State Journal published a lengthy article about the state house, including the following description of the House chamber:

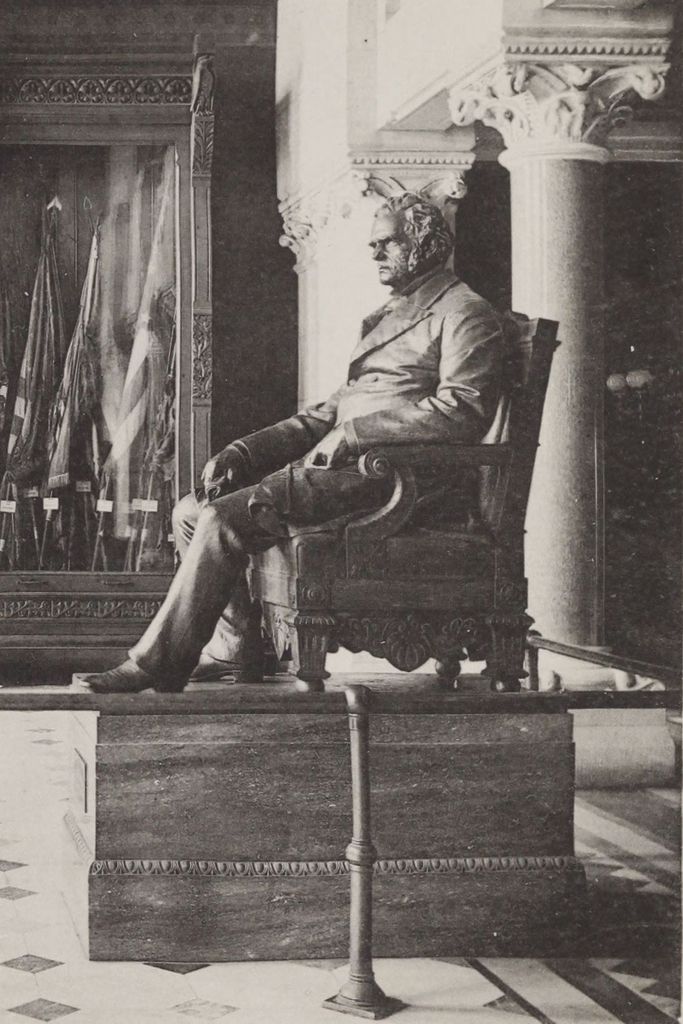

The Representatives’ Hall is 69 9 by 67 feet, 31 feet high, and is in the form of the letter D. The walls are relieved by pilasters fluted, having bases supported by pedestals and carved capitals, of the Corinthian order, supporting an enriched entablature, from which springs a cove to the flat ceiling, terminating in a moulded border and stopped at each intersection by a moulded pendant. The panels of the cove and ceiling are double sunk, exceedingly well proportioned, moulded and ornamented, and are continued in curves parallel to that of the wall. The centre piece is very graceful in outline and is eighteen feet in diameter, and bears unmistakable signs of originality.

The rear end of this room is finished like the sides, but without the cove at the top of the entablature, and by the skilful treatment of the Architect, has not the heavy stolid appearance of the attic base usually accompanying the natural order of finish. It has neat plain panels proportioned to the place, and in the centre one, directly over the Speaker’s desk, is placed the Coat-of-Arms of the State, carved in wood, gilded and painted, with scroll work at base. It was executed by John A. Ellis of Cambridge, Mass., and is a piece worthy of any artist. The various cornices and panels in the ceiling of the room are enriched with stucco ornaments just sufficient for an easy relief and to give a graceful effect to the whole.

The rear of the Hall has a raised platform, 7 feet wide and 67 feet long, approached by a flight of four stairs on either side of the Speaker’s Desk, protected in front by a black walnut moulded rail rising 6 inches above the floor. The seats on this platform, for the use of the Senate in Joint Assembly, were designed for the place and are appropriate to it. The Bar of the House is 17 by 38 feet, and from it rises at each side the inclined plane, on which are secured the Representatives’ desks and chairs. These are placed on circles, corresponding to the shape of the room. By the arrangement of desks, each Representative has ample room for writing and speaking. The Speaker’s and Clerk’s desks, tho’ plainer in style than that of the President of the Senate, are well proportioned and beautiful in finish.

Although not specifically mentioned in this description, perhaps the most notable decorative feature in the chamber was the massive portrait of George Washington, which is seen here in these two photos. It was painted in 1837 by George Gassner, based on an earlier painting by Gilbert Stuart, and it had originally hung in the old state house. It was rescued from the building during the 1857 fire, and it was subsequently placed in the House chamber of the new state house, where it has remained ever since.

At the time of this building’s completion, the state had 239 representatives, with one representing each town, regardless of population. This meant that Burlington, with an 1860 population of 7,713, had the same representation here as Glastenbury, which had a population of 47. This system would remain in place for the next century, even as the imbalanced worsened, with the state’s cities growing larger, and the small towns getting smaller. Eventually, though, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a series of rulings in the 1960s that established the one man, one vote principle for state legislatures, requiring Vermont and many other states to reapportion their legislatures based on population.

The first photo was taken within about a decade or two after the building was completed, probably in the late 1860s or early 1870s. Perhaps the most notable representative during this period was John Calvin Coolidge, who represented the town of Plymouth from 1872 to 1878. At the time, Coolidge had two young children at home, including his son Calvin, the future president, who was born in 1872. Many years later, the elder Coolidge would serve in the state senate from 1910 to 1912, and his last government position was as a justice of the peace, in which capacity he swore in his son as president in 1923.

Today, around 150 years after the first photo was taken, the House chamber now has far fewer desks for representatives. This was the result of the 1965 reapportionment, when the state legislature reduced the size of the House from 246 to 150, with electoral districts that were based on population rather than town boundaries. Overall, though, the House chamber has remained remarkably well-preserved in its original appearance. It is still in active use by the Vermont House of Representatives, and it is one of the oldest state legislative chambers in the country that has survived without any major remodeling.