The New Hampshire State House in Concord, around 1900-1909. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The State House in 2019:

Completed in 1819, the New Hampshire State House is among the oldest state capitol buildings in the country, and it is the oldest one with both of its original legislative chambers still in use. Despite this, though, the building has undergone substantial changes over the past two centuries, on both the interior and exterior. The original design was the work of architect Stuart James Park, and it was two stories in height, with a cupola at the top and an exterior of locally-quarried granite.

By the mid-19th century building had become too small, and the city of Manchester offered to build a new capitol building if the state government relocated to the much larger industrial city to the south. However, the state ultimately chose to remain in Concord, and hired noted architect Gridley J. F. Bryant to renovate the building. His expansion, which is shown in the first photo, was completed in 1866. It included a mansard roof, which allowed for more interior space, along with the addition of a columned portico here on the east facade. Bryant also replaced the old cupola with a much larger dome, although he retained the wooden eagle that had originally sat atop the cupola.

By the time the first photo was taken in the early 20th century, the building was again too small, which reignited the debate about moving the capital to Manchester. Once again, though, the building was expanded instead of being abandoned, and this time the renovations were designed by the Boston architectural firm of Peabody and Stearns. Most significantly, this project included a large addition to the rear of the building for the governor’s office, Executive Council chambers, and other government offices.

The other major change, which is much more visible from this angle, involved removing the 1860s mansard roof and adding a full third floor, topped with a flat roof and a granite balustrade along the roofline. Like the rest of the building, the third floor was constructed of granite, but the blocks were sourced from a different quarry. As a result, the present-day photo shows a noticeable difference in the shade of the granite between the second and third floors.

This project was completed in 1910, and the building has remained in use ever since. Today, aside from the age of its legislative chambers, the building is also significant for housing by far the largest state legislature in the country. With 400 representatives and 24 senators, the New Hampshire General Court is nearly twice the size of the next two largest state legislatures, and its House of Representatives is almost the same size of the United States House of Representatives.

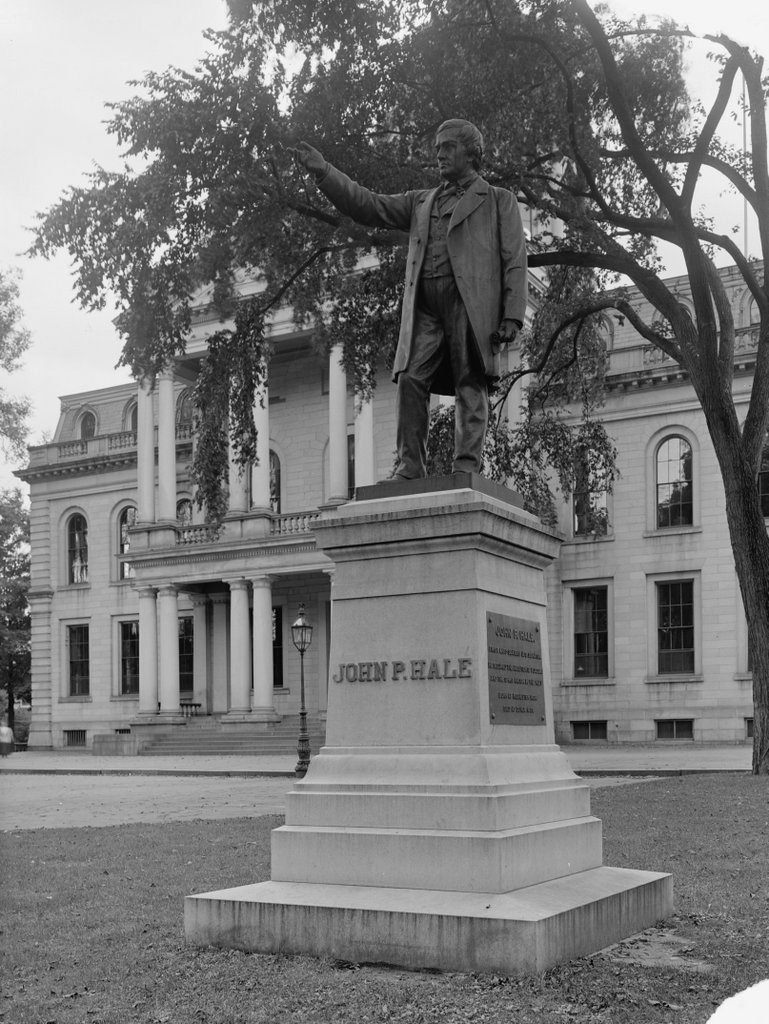

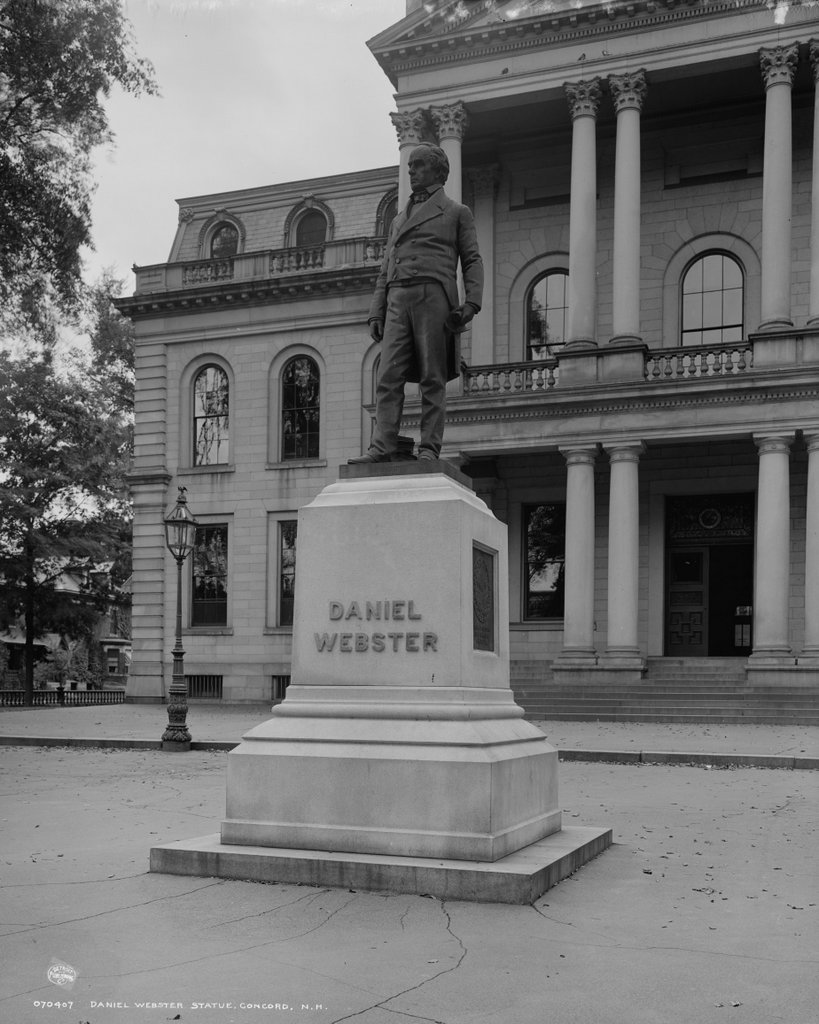

Well over a century after the first photo was taken, the removal of the mansard roof is still the only significant change to this scene. Otherwise, this scene has remained essentially the same as it looked at the turn of the 20th century, and even the two statues are still standing in front of the State House, honoring two famous native New Hampshirites. On the left is General John Stark, and further in the distance on the right is Daniel Webster. The gold dome is also still topped with an eagle, although the current one is a copper replica of the original wooden one, which was removed in 1957 and put on display inside the State House.