The railroad station at the corner of Washington and Norman Streets in Salem, around 1910. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2017:

Salem was a prosperous seaport throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries, with a fleet of sailing ships that brought goods to the city from around the world. Given its location on the north shore of Massachusetts, it was heavily dependent on the sea for its commerce, but in 1838 the first railroad line was opened to Salem, connecting the city to East Boston by way of the 13-mile-long Eastern Railroad. The line initially ended here in Salem, at an earlier station on this site, but in 1839 it was extended north to Ipswich, and then to the New Hampshire state line the following year.

The 1838 railroad station was built at the southern end of downtown Salem, meaning that the extension of the line would have to pass directly through the center of the city. In order to accomplish this, the railroad dug a 718-foot tunnel directly underneath Washington Street, allowing trains to pass through without disrupting downtown Salem. The incline for the tunnel began immediately north of the station, just out of view to the left of this scene, and it re-emerged just north of present-day Federal Street. The 1917 book The Essex Railroad, by Francis B. C. Bradlee, provides a description of the 1839 construction of the tunnel:

In order to build it the old Court House, together with stores and other buildings standing south of Essex street, were demolished. Washington street was laid open throughout its entire length and a wide ditch was dug, much trouble being experienced from the sandy nature of the soil. Residents on the side of the street boarded up their house fronts and moved away for some weeks. The sidewalks were piled with gravel. A stone arch was built in the open ditch, and when this was finished the gravel was back-filled as far as possible and the surface restored. Three air holes surrounded with iron railings came up from the tunnel through the street for ventilation, but when the locomotives began to burn coal they were done away with. All this work was done on the most elaborate plans and models, it being considered one of the largest pieces of granite work ever undertaken up to that time in New England.

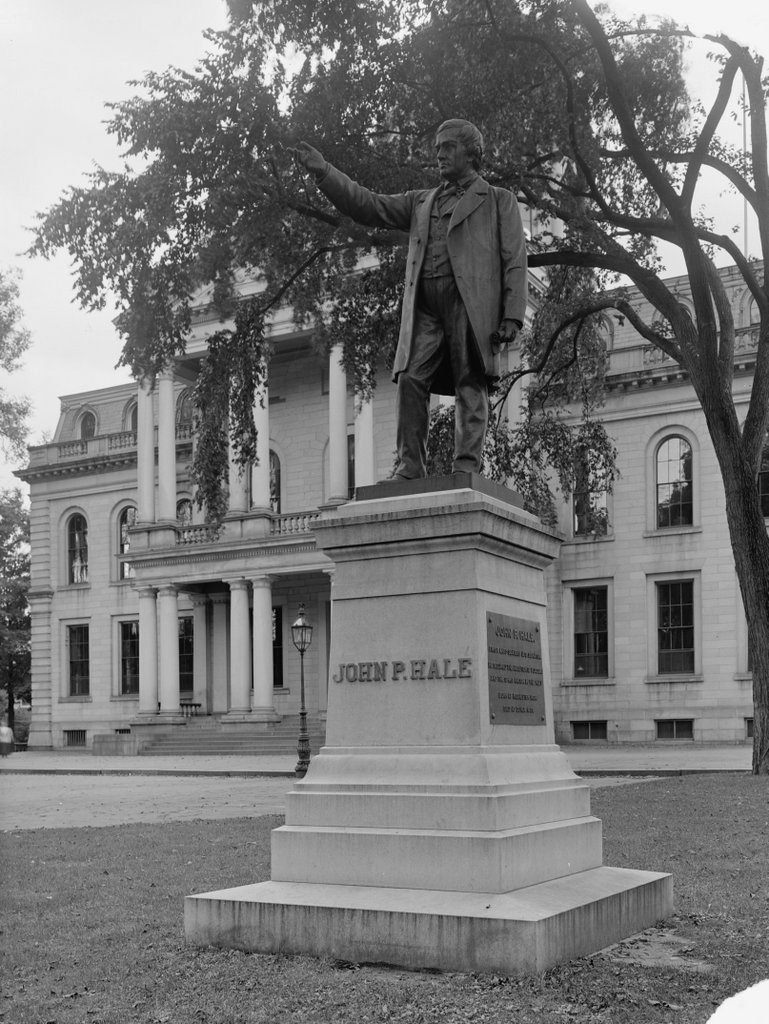

The original railroad station was used until 1847, when it was replaced by the one in the 1910 photo. It was designed by prominent architect Gridley J. F. Bryant, with a castle-like appearance that included two large crenellated towers on the north side of the building, as seen here. Trains passed directly through the building, and under a granite arch between the towers that resembled a medieval city gate. The interior originally included three tracks, and the upper level of the station housed the offices for the Eastern Railroad, including those of the president and the superintendent.

The station was badly damaged by an April 7, 1882 fire that started when a can of flares exploded in one of the baggage rooms. The wooded portions of the building were destroyed, but the granite exterior survived, and the rest of the station was soon rebuilt around it. Then, in 1884, the Eastern Railroad was acquired by its competitor, the Boston and Maine Railroad, and the station became part of a large railroad network that extended across northern New England. The first photo, taken around 1910, shows the a side view of the front of the building, with the original granite towers dominating the scene. In the lower left, a locomotive emerges from the station, while railroad flagmen – barely visible in front of the train – warn pedestrians and vehicles on the street.

In 1914, much of the area immediately to the south of the station was destroyed in a catastrophic fire that burned over a thousand buildings. The station itself survived, though, and remained in use for more than a century after its completion. However, it was demolished in 1954 in order to extend the tunnel south to its current entrance at Mill Street. By this point, intercity passenger rail was in a serious decline, due to competition from automobiles and commercial airlines, and the replacement station was a much smaller building on Margin Street, just south of the new tunnel entrance.

The 1950s station was used until 1987, when the present-day station was opened at the northern end of the tunnel, at the corner of Washington and Bridge Streets. Salem is no longer served by long-distance passenger trains, but it is now located on the MBTA Newburyport/Rockport commuter rail line, and trains still pass through the tunnel that runs underneath Washington Street. On the surface, though, there are no recognizable landmarks from the first photo, and today the scene is a busy intersection at the corner of Washington and Norman Streets. The former site of the historic station is now Riley Plaza, a small park that was dedicated in 1959 and named in honor of John P. Riley (1877-1950), a Salem resident who was awarded the Medal of Honor for his service in the Spanish-American War.