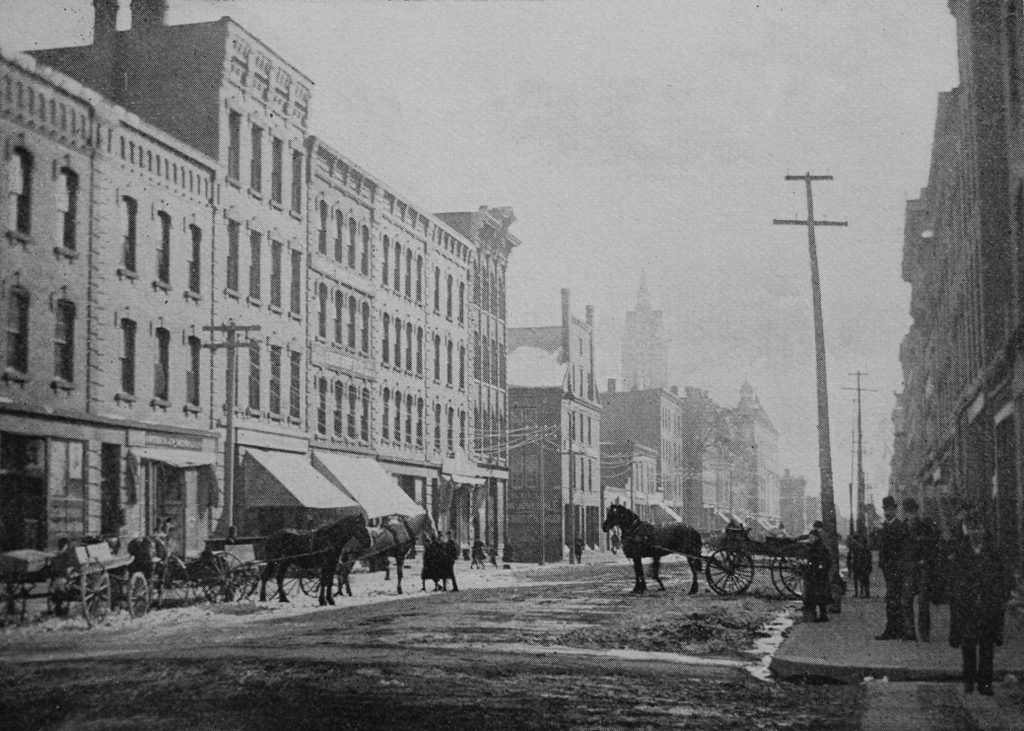

Looking south on High Street from Lyman Street in Holyoke, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

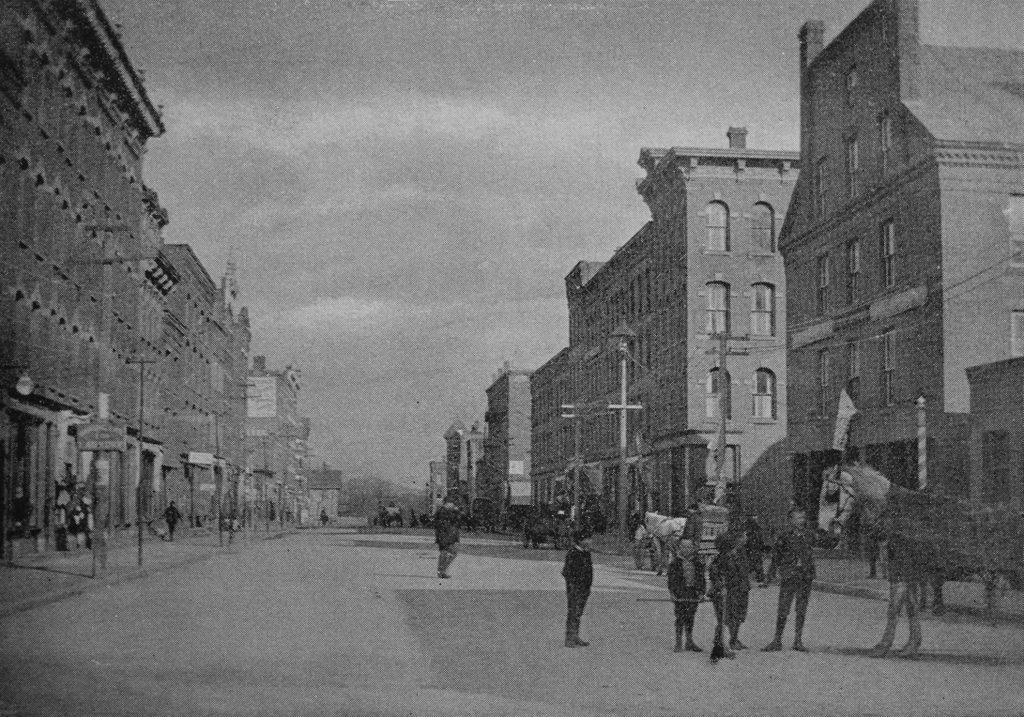

The scene in 2017:

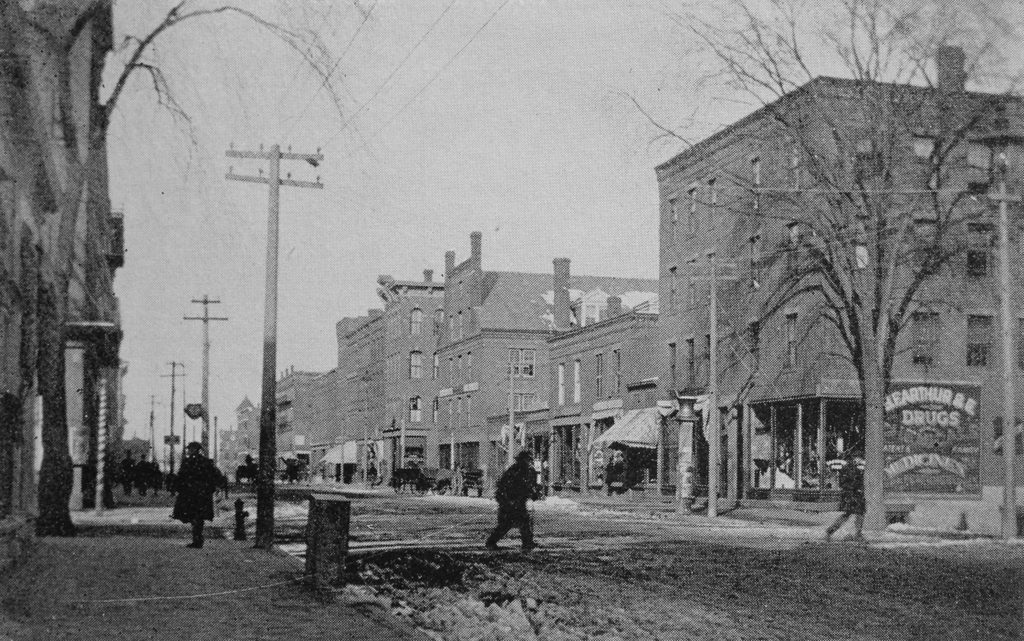

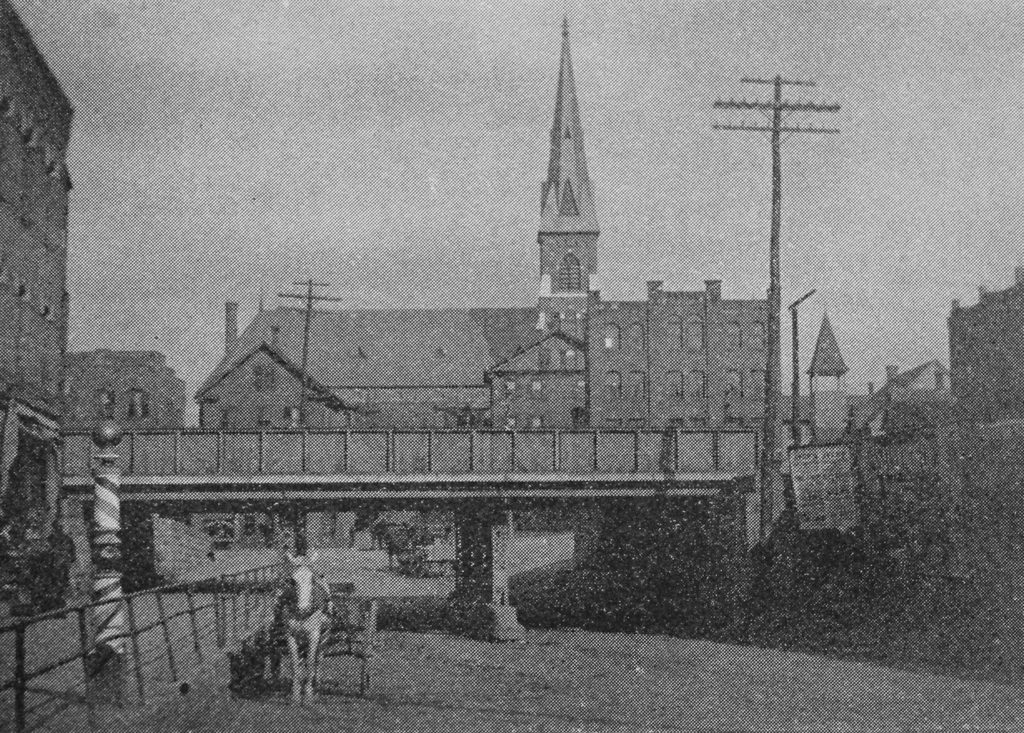

This scene shows the same block of High Street as this previous post, just from the opposite direction. As mentioned in that post, these buildings were mostly built around the 1860s and 1870s, with the oldest probably being the Fuller Block in the center of the photo, which dates back to around the 1850s. Closer in the foreground, there are seven very similar Italianate-style brick commercial blocks. The six closest to the camera were all built around the same time, probably about 1870, and the one near the center of the photo was built a little later, around 1878. Holyoke’s Gothic-style city hall also dates back to around this time, having been completed in 1876, and its tower rises in the distance of both photos.

Today, this scene has not significantly changed in the past 125 years. Everything on High Street to the north of Lyman Street was demolished in the 1970s as part of an urban renewal project, but most of the historic High Street buildings are still standing to the south of Lyman Street. The Fuller Block is still here, as are most of the other buildings beyond it, and five of the seven buildings in the foreground are also still standing. The building on the far left, at the corner of Lyman Street, is gone, as is the one at the corner of Oliver Street, but otherwise this scene retains much of its late 19th century appearance. Because of this, the buildings along this section of High Street are now part of the North High Street Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1986.