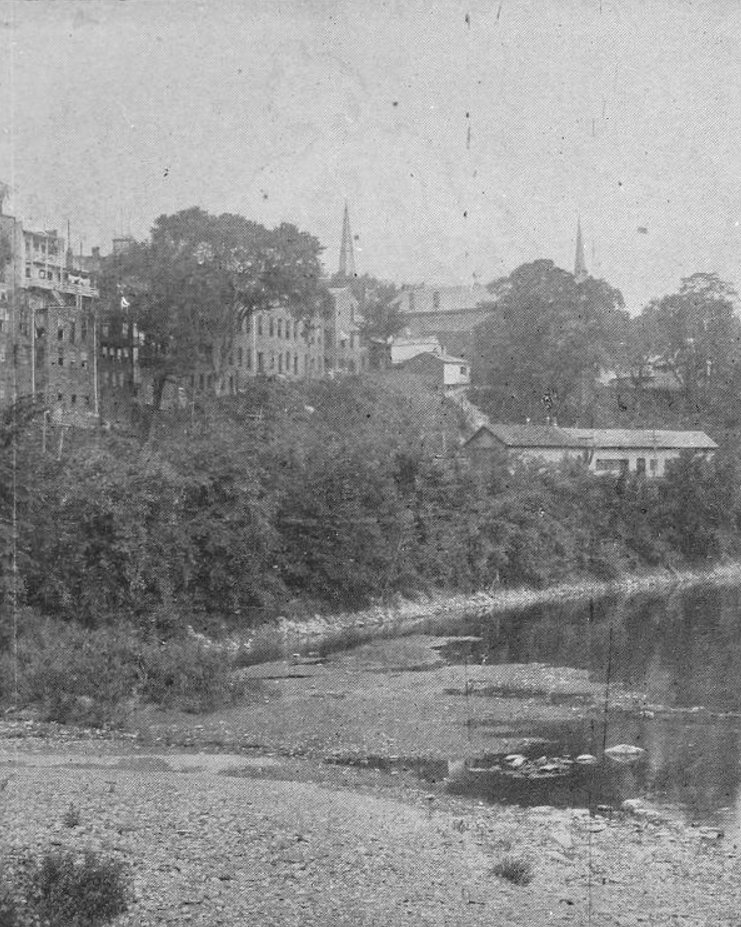

The scene looking north on Main Street from the Whetstone Brook in Brattleboro, apparently in the aftermath of the October 4, 1869 flood. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The scene in 2017:

The first photo is undated with no caption, but it almost certainly shows the aftermath of the October 4, 1869 flood, which was among the most disastrous floods in the history of Brattleboro. The town has always been vulnerable to flooding, given its location on the banks of the Connecticut River, but the majority of the damage in this particular flood was caused by the small but fast-moving Whetstone Brook, which passes through downtown Brattleboro in the foreground of this scene. Originating in the hills to the west of here, the Whetstone provided the water power for many of Brattleboro’s early industries. However, this proximity to the brook also made these factories vulnerable to flooding, which could come with little warning.

Although rapid changes in the water level were not uncommon, the October 1869 floodwaters were higher than any in recorded history up to that point, and came after 36 hours of heavy rainfall. The flooding began shortly after 11:00 on the morning of October 4, and initially the primary concern was removing goods from the basements of homes and businesses on Flat Street, which runs along the north side of the brook. However, within ten minutes the water level had risen to the point where the focus shifted from saving property to saving lives. The book Annals of Brattleboro, 1681-1895 provides a detailed description of the subsequent events:

John L. Ray’s livery stable floor was completely covered with water. Many ready and willing hands were there to seize his horses by the bridle and lead them to a place of safety; all his buggies and horses were taken to high ground on Main Street. So suddenly did the waters spring upon the workmen in the blacksmith shop of Mr. Hall, that the floor was afloat and the workmen were obliged to break through a back door and climb up a stone wall and take shelter upon Elliot Street. A frame workshop just beyond the smithy was washed from its foundation and swung completely around. Mr. Dunklee, occupying the first house on the right-hand side of Flat Street, had just begun to gather up his things on the first floor of his tenement when he was obliged to call for help for the rescue of himself, wife and two other females. Help was promptly given him by Mr. John Rogers of the Revere House, who did yeoman’s service and saved them, although they were all pretty well drenched. In the next house resided Mr. Frank Holding, whose wife had been for four weeks dangerously ill with typhoid fever; their lower floor was completely inundated. Ropes and boats were procured by the spectators, who numbered hundreds, and after much peril and great exertion, the family were taken alive. The house of Willard Frost, on the lower side of the street, was in a peculiarly exposed situation. Fences were broken down by the ferocity of the current, the woodshed was veered around, the barn was shaken on its foundation, and inevitable destruction seemed imminent. The house was occupied by the female members of Mr. Frost’s family together with Mr. Eugene Frost, Mr. Wells Frost and his mother. They all went to the upper chamber of the house and there made signals of distress from the windows to the assembled multitude on Elliot Street. The rapid current which eddied and whirled around the house on all sides made it next to impossible for a boat to live in the waters. Several attempts were made to reach the house, but without success and these people suffered agonies untold for many minutes, until at last the timbers which had floated between the buildings formed a raft, on which they safely passed to the shore.

The large dam at B. M. Buddington’s gristmill was washed away, and the tannery which stood below was demolished and two thousand hides taken down the stream. Spenser & Douglas’s shop was entirely swept away and the road all along ruined. The bridge near the old woolen factory went down, on which two ladies had stood a moment before, barely escaping with their lives. The swollen stream then swept over Frost meadow reaching Estey & Company’s organ factory, doing no damage to the buildings, but carrying off thousands of feet of lumber and tearing up the road badly. On the south side of the brook, Woodcock & Vinton’s canal for about two hundred rods was torn out and one of the buildings and some paper injured. The flood swept away in a moment, Dwinell’s furniture shop with all its contents, furniture, tools, stock and account books, the Main Street bridge, A. F. Boynton’s shoe shop, office of I. K. Allen, lumber dealer, and Boyd’s fish market. Several men were in the market, among them the proprietor – he felt the building tremble and singing out “Run for your lives,” quickly he followed his flying guests. He sprang out of the door, turned around to look and saw nothing but a mass of water where a second before had stood his place of business. On the other side the planing mill of Smith & Coffin was cleaned out of its machinery, tools, etc.; the machine shop of Ferdinand Tyler was struck by the timbers and a part of the underpinning knocked away, the sawmill near the bridge and the foundry below were swept into the Connecticut with all their contents.

Nearly all of the bridges across the Whetstone Brook were destroyed by the flood, including the one here on Main Street. The first photo shows a large ditch where the bridge had once been, with wreckage strewn across the scene. The flood caused an estimated $300,000 in damage, equivalent to about $5.6 million today, and also killed two people. One of the victims was Adolph Friedrich, a Prussian immigrant sho left behind a wife and five young children. Twelve years earlier, Friedrich had survived the sinking of the treasure ship S.S. Central America, which was lost in a hurricane off the coast of the Carolinas. He had been returning from the gold fields of California, but he lost his fortune in the shipwreck. He eventually made his way to Brattleboro, where he found work at the Estey Organ Company. Friedrich was working there when the flood hit, and was swept downstream on a raft of boards. He was last seen going over the waterfall near the Main Street bridge, and his skeletal remains were later discovered on a riverbank. The other victim of the flood was Kittie Barrett, a 16 year old girl who had been watching debris float by at the tannery. She was killed when the upstream dam broke, and her body was recovered about a quarter mile downstream.

Today, nearly 150 years after this disastrous flood, this scene has remained remarkably unchanged. Some of the old buildings, particularly on the left side of the street, were replaced in the late 19th or early 20th centuries, but overall the area retains a similar scale in both photos. The right side, though, has been well-preserved, and a number of the buildings from the first photo are still there. The most noticeable of these is the Van Doorn Block on the far right, with its large, pedimented gable. Built in 1850, the brick building survived the 1869 flood and still stands, with few noticeable changes over the years. Further up the street, other survivors from the first photo include the Devens, Exchange, and Cutler Blocks, which were built in the early 1840s and form a continuous facade from 85 to 97 Main Street. Even further in the distance, near the center of the scene, are several other mid-19th century buildings that are still standing. Today, all of these buildings form part of the Brattleboro Downtown Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.