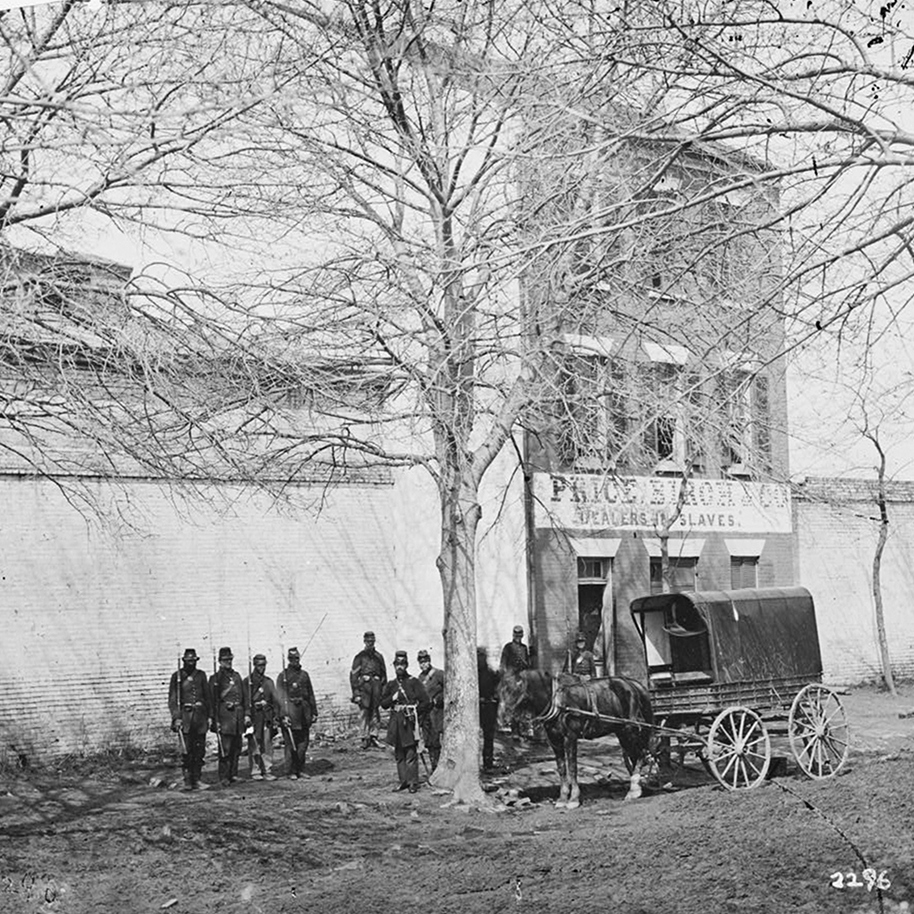

The Five Mile Point Light at the entrance to New Haven Harbor, around 1900. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2021:

New Haven Harbor has been marked by a lighthouse since 1805, when the first one was constructed here on this site at the southeast edge of the harbor. It was commonly known as Five Mile Point Light, because of its distance from downtown New Haven. The original tower was 30 feet tall and built of wood, but by the late 1830s both it and the keeper’s house were badly deteriorated. Both buildings were replaced in 1847, and the new lighthouse was substantially larger than the older one. As shown in these two photos, it is octagonal in shape and constructed of local brownstone, and it stands 80 feet above the ground. Its design is very similar to many of the other early 19th century lighthouses in Connecticut, including New London Harbor Light, Lynde Point Light, Black Rock Harbor Light, and Falkner Island Light.

The new lighthouse was constructed by local builder Marcus Bassett, and the work evidently progressed quickly. Congress appropriated funds for it on March 3, 1847, and it was nearly completed by September, when an article appeared in the New Haven Journal, praising the new lighthouse:

New-Haven harbor during easterly storms, is the refuge of an immense number of craft, but its entrance from the east has always been difficult, if not dangerous, because the light-house cannot be seen until near the rocks upon which it stands. The government erected a new house for the keeper recently, but the new light-house, which is nearly ready for use, is the object of special admiration. Standing but a few rods from the old one, it rises in towering majesty by its side, and now may be seen in every direction where the other was wholly concealed. It will be of immense benefit to New-Haven harbor and also add to the security of the navigation of the Sound.

As was the case with most other American lighthouses of the era, Five Mile Point Light was maintained by a keeper who resided here on the property. Lighthouse keepers were primarily responsible for lighting and extinguishing the lantern, but other routine duties included maintenance and repairs to the buildings and equipment. However, because of their locations at hazardous points along shipping routes, keepers were also occasionally called upon to assist sailors in distress. Here at Five Mile Point, keeper Merritt Thompson, who served from 1853 to 1860, was often involved in such rescues, with his 1884 obituary noting that “when he was keeper of the lighthouse it was his good fortune to be instrumental in saving lives on a number of occasions when boats would be upset in the harbor,” and that “many stories are told of his daring and humanity in emergencies calling for personal risk and quick action.”

The 1860 census shows Thompson living here at the lighthouse with his wife Julia and their six children, who ranged in age from 11 months to 14 years. However, he was subsequently dismissed from the post, and went on to work as a harbor pilot here in New Haven. An 1861 letter to the editor, published in the Columbian Register, suggested that this was a political move, and that he was replaced by a Republican partisan because of Abraham Lincoln’s electoral victory in 1860. The writer questioned the qualifications of any replacement, and observed that “the removal has caused a burst of indignation among all our citizens,” and concluded the letter with some sarcasm, saying “I trust none of our citizens will allow themselves to be capsized in the vicinity of the light house, for the next four years.”

The new lighthouse keeper was Elizur Thompson, who was not related to his predecessor. Despite this anonymous writer’s doubts about his abilities, he go on to serve here for many years, first as a keeper and later as an employee of the United States Signal Service. His family also helped maintain the lighthouse, including his wife Elizabeth and two of their sons, each of whom received assistant keeper salaries at various times over the years. He was dismissed in 1867 by the Andrew Johnson administration, for reasons that were evidently as political as his initial appointment had been, but he was subsequently reappointed in 1869, after Republican Ulysses S. Grant became president.

During the 1870 census, Elizur and Elizabeth were 61 and 59 respectively, and they lived here at the lighthouse with their 24-year-old son George and their 18-year-old daughter Ella. However, Elizabeth died a year later, and in 1877 Elizur remarried to Ellen Pierce, a widow who was about 30 years younger than him. She had a son, Burton, from her first marriage, and he was 13 years old and living with them during the 1880 census.

In the meantime, in 1873 the federal government began construction of Southwest Ledge Light, located on a rocky ledge about a mile offshore from here. Because this new lighthouse was much closer to the main shipping channel, it rendered Five Mile Point Light obsolete, and the light was deactivated after Southwest Ledge was completed in 1877. Elizur Thompson was then appointed as the first keeper of the new lighthouse, and his son Henry became the assistant keeper. He remained there for four more years, until his retirement in 1881, and Henry then became the main keeper of Southwest Ledge.

Following his retirement, Elizur and Ellen returned to the old Five Mile Point Light, where he was allowed to live, rent-free, for the rest of his life. During this time, he worked for the United States Signal Service, displaying flags from the old lighthouse to provide weather reports for passing merchant vessels. Both Elizur and Ellen faced health scars in the mid-1880s, beginning with a head injury that the elderly Elizur suffered in 1884, when he slipped and hit the back of his head on a rock while trying to launch a boat here on the beach. Then, in June 1885 Ellen underwent major surgery in New York to remove a large tumor. Newspaper reports described her as being in critical condition and doubted whether she would survive, but she ultimately recovered and returned to New Haven in early August.

Elizur carried out his duties here at the lighthouse until his death in 1897, when he was 87 years old. Ellen had taken over these responsibilities during his final illness, and after his death she was formally appointed as his successor. As described in the Morning Journal and Courier following her appointment, the signal station “has been a great boon to the sailors, since it has warned them of impending storms and furnished them the opportunity to come within the shelter of the harbor.” The article described how the weather reports arrived in downtown New Haven and were then telephoned to the lighthouse, where Ellen would hoist the appropriate flags. The article then concluded by remarking that “the task is anything but an easy one for a woman, especially in stormy weather.” She would retain this post until her death in 1901, at the age of 60.

The first photo was taken around 1900. Assuming this date is accurate, Ellen Thompson would have still been living and working here, and the tall pole atop the lighthouse was likely where she hoisted the flags. The photo also shows the keeper’s house on the right side, connected to the lighthouse by an enclosed wooden walkway. On the other side of the lighthouse, in the center of the photo, are four Civil War-era Rodman cannons that were installed here during the Spanish-American War in 1898. These obsolete guns were evidently more for show than anything else, and were likely more effective at reassuring locals than at dissuading Spanish warships. In any case, these guns were never tested in combat during the short-lived war, and within a few years they were removed and incorporated into several different local Civil War memorials.

No longer necessary for either navigational aids or civil defense measures, this area around the old lighthouse subsequently became an amusement park, known as Lighthouse Point Park. Like many other early 20th century amusement parks, it was developed by a local trolley company as a way of increasing ridership on otherwise quiet weekend trolleys. The park featured attractions such as a carousel, along with a beach and fields for athletic events. Even prominent baseball stars such as Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb made appearances here at Lighthouse Point and participated in exhibition games.

The amusement park was subsequently acquired by the city, but it began to decline after the 1920s, and most of the park buildings were demolished by the mid-20th century. The site has continued to be used as a public park, though, and it continues to be a popular destination for its beach and for other recreational activities, including its restored carousel. However, the most prominent landmark here at the park continues to be the historic lighthouse. Despite not having been used as a lighthouse for nearly 150 years, both the tower and the keeper’s house are still standing, with few major changes since the first photo was taken, aside from the loss of the covered walkway.