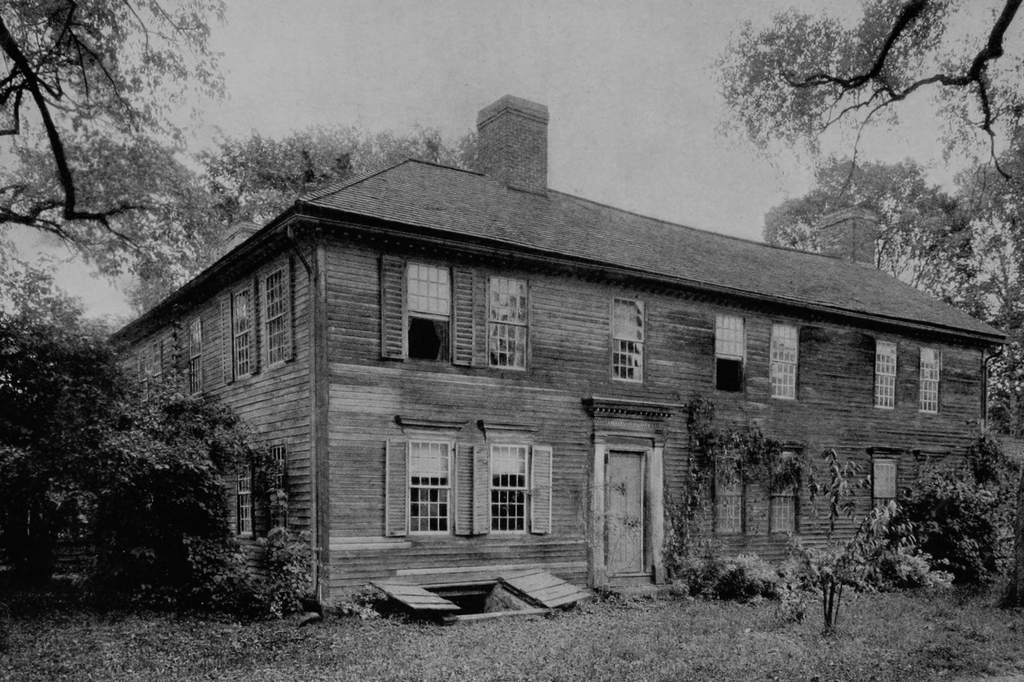

The Barnard Tavern and adjacent Frary House in Deerfield, around 1920. Image from An Architectural Monograph on Old Deerfield (1920).

The scene in 2023:

This building stands on the east side of Old Main Street in Deerfield, just south of the common in the historic town center. It consists of two separate but adjacent structures, with the Frary House in the distance on the left and the Barnard Tavern here in the foreground. The Frary House is the older of the two sections, dating to around the 1750s, and the tavern was constructed around 1795.

As was the case with late 18th and early 19th century taverns across New England, the Barnard Tavern was not only a place for travelers to stop and have a meal or spend the night; it was also an important community hub for locals, and it was frequently used as a gathering place. The building had the bar room and kitchen on the first floor, while the upper floor housed a large assembly room that was used for a variety of meetings and other public events.

By the late 19th century, both buildings were in poor condition. However, in 1890 the property was purchased by teacher, historian, and author C. Alice Baker (1833-1909). Originally from Springfield, Baker had attended Deerfield Academy. During the 1850s she taught at a school in Illinois, and then at Deerfield Academy, and then started her own school in Chicago. She subsequently returned east, and became active in studying local history, particularly the history of Deerfield. She never married, but she lived with another woman, Susan Lane, who was described in contemporary sources as her “lifelong companion.” After purchasing this building in Deerfield, Baker worked to restore it, and she made the Frary House side into her home.

The restored Frary House/Barnard Tavern became an important landmark in Deerfield, and it was often photographed in publications about the town, as was the case with the top photo around 1920. The building was at one point owned by the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, but it is now owned by Historic Deerfield. It is one of the many properties that the organization has preserved, and both halves of the building are open to the public for guided tours on a regular basis.