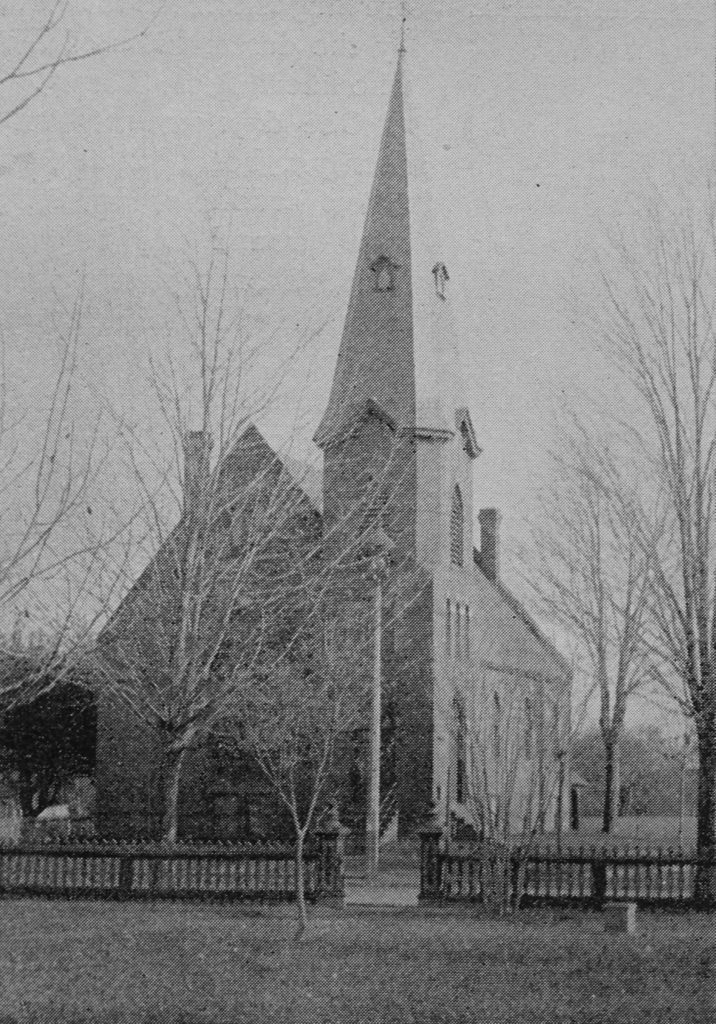

The First Baptist Church, at the corner of Northampton and South Streets in Holyoke, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

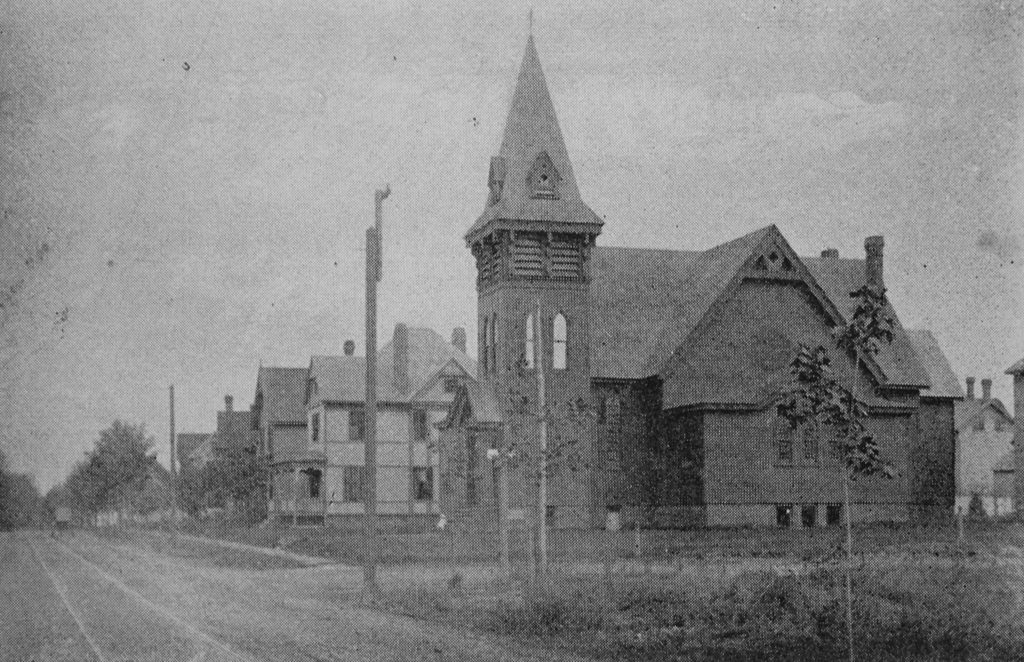

The church in 2017:

Holyoke’s First Baptist Church is significantly older than Holyoke itself, and was originally incorporated in 1803, back when Holyoke was still part of West Springfield. At the time, this northern section of West Springfield was known as Ireland Parish, and most of its development was centered along present-day Northampton Street. The First Baptist Church built its first permanent church building here on this site in 1826, at the corner of Northampton and South Streets, and over the next decade the congregation steadily grew, eventually peaking at 179 in 1835.

Holyoke was incorporated as a separate town in 1850, and at the time, it was being transformed into a major industrial center. However, this development was concentrated more than a mile to the east of here, along the banks of the Connecticut River. This drew people away from the old village center on Northampton Street, and First Baptist Church steadily lost members, who moved closer to the new town center. By 1879, church membership had dwindled to just 69, but, despite its small size, the congregation embarked on a building project, demolishing the old wood-frame building in 1879 and replacing it with a new brick, High Victorian Gothic-style building that was completed in 1880, on the same site as the old church.

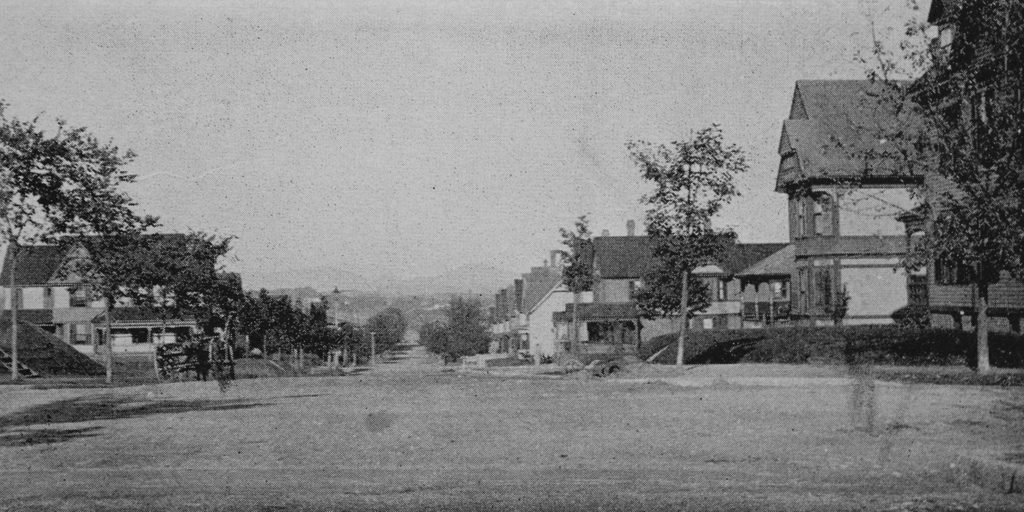

This proved to be a wise move, because by the late 19th century, the surrounding neighborhood was being developed as a suburban residential area. Originally known as Baptist Village, the neighborhood became Elmwood, and the influx of residents helped to grow the church. By the first decade of the 20th century, membership had tripled from its 1879 numbers, requiring an addition in the right side, which was built in 1906. Since then, the exterior has not changed significantly, and First Baptist Church remains an active congregation that still worships here in this building, more than 125 years after the first photo was taken.