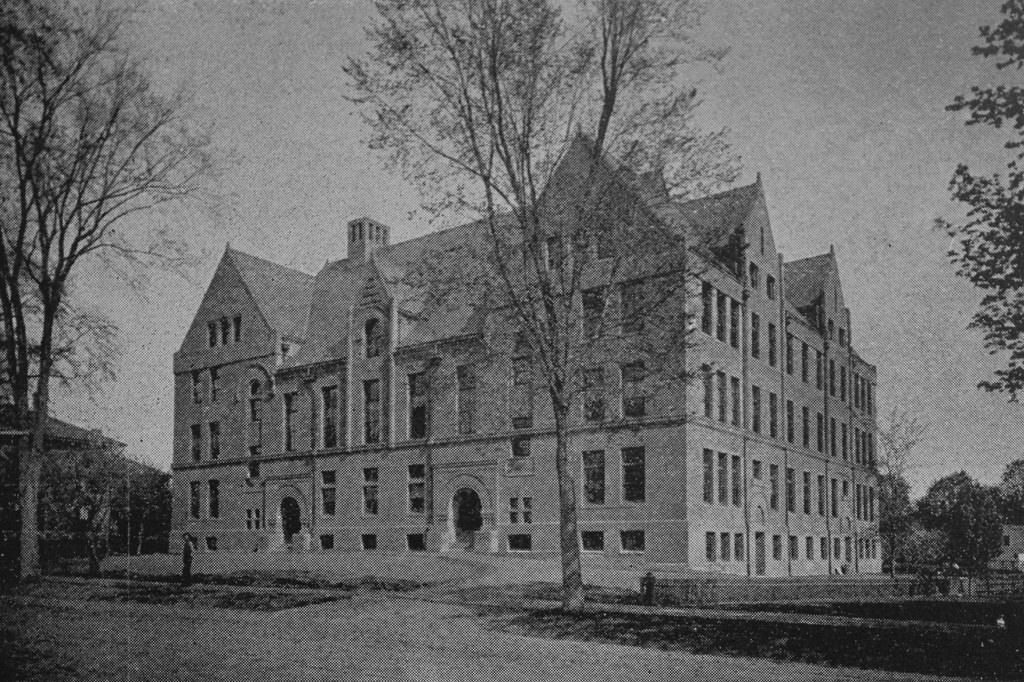

The Westfield Normal School on Court Street in Westfield, around 1891. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1891).

The building in 2018, which is now used as Westfield City Hall:

The mid-19th century saw the development of public normal schools, which were colleges that focused on training public school teachers. Here in Massachusetts, a system of normal schools was pioneered by education reformer Horace Mann, who opened ones in Lexington and Barre in 1839, and in Bridgewater a year later. The Bridgewater school has remained there ever since, and it is now Bridgewater State University, but the other two schools soon relocated. The Lexington Normal School moved to Newton in 1843 and later to Framingham, becoming the precursor to Framingham State University, and the Barre Normal School came to Westfield in 1844, eventually becoming Westfield State University.

Here in Westfield, the school’s first long-term home was a building at the corner of Washington and School Streets, which was completed in 1846. This building was used throughout much of the 19th century, but by the late 1880s it had become too small for the school’s growing programs. As a result, in 1889 the state purchased this lot on Court Street, and later that year construction began on a new, much larger building. It was originally expected to be completed in time for the fall of 1891, but construction delays postponed its opening until April 1892. The first photo was probably taken around this same time, as the small leaves on the trees seem to suggest that it is either late April or early May.

The building was designed by the noted Boston firm of Hartwell and Richardson, and it featured a Romanesque-style exterior of brick with brownstone trim. Its footprint was L-shaped, with the main section facing Court Street and a wing extending back in the direction of King Street, as seen on the right side of the photo. This wing originally housed the training school, with classrooms for the various grade levels that were taught by the student teachers here. These were accessed via the basement-level doors of the wing, while the main entrances for the normal school itself were at the front of the building.

The state Board of Education, in its annual report published several months before the building opened, provided the following description of the interior:

To the left of the south-west entrance are the zoölogical, botanical, mineralogical and geological laboratories, fitted with appropriate appliances; and to the right of this entrance is the reception room, and beyond a large room for the critic, while across the corridor, which traverses the centre of the L-shaped building, are the large cloak room for women, with toilet room and a teacher’s room.

There are three stairways which carry from the basement up through the building. Two of them are next the entrances for the normal school on the south side. The third is in the L, and leads directly from one of the basement entrances. There is a lift near this staircase.

On the second floor there are three rooms: toward the east there are recitation rooms, with a women’s retiring and toilet room, and a book store-room; toward the west a recitation room, the principal’s room, the reading-room and book alcove; and in the center part of the building the large school-room sixty feet square.

On the third floor is a completely fitted chemical laboratory, with a teachers’ room, weighing-room, and a supply room opening out of it; the apparatus room and physical laboratory, fully equipped; and between these two laboratories, so that it can be used from either, a lecture room with raised tiers of seats.

Over the large school-room is a series of studios, and at the western end of the building are a recitation room, a cast room and a drawing room. Above the two end portions there are unfinished attics.

In the basement are the janitor’s room, men’s coat-room and toilet; the gymnasium with the men’s dressing-room and baths on the one side, and on the other women’s bath-rooms, with a staircase leading up to the women’s toilet room above; space for coal and boilers, and toward the east, play and toilet rooms for girls and boys, and a large work room.

Overall, the building was designed with a capacity of 175 normal school students, plus 125 children in the training school. A subsequent Board of Education annual report, covering the 1892-1893 school year – this building’s first full year in use – indicates that it was not quite at capacity, but it was close. During that year, it had a total of 155 students, including 27 who graduated at the end of the year. At the time, the student body was still overwhelmingly female, with only six men enrolled in the school and just one in the graduating class.

The report also provides interesting demographic information about the students. Of the 155 students, 26 had prior teaching experience, and 78 were receiving some sort of financial aid from the state. The vast majority were from Massachusetts, mostly from the four western counties of Hampden, Hampshire, Franklin, and Berkshire counties, but there were also some out-of-state students, including five from Vermont, four from Connecticut, two each from New Jersey, New Hampshire, New York, and Rhode Island, and one each from Washington D.C., Virginia, Tennessee, and Nebraska.

Another table in the report classified students based on their fathers’ occupations. The most common was farmer (26), followed by skilled workmen (15), factory officials (8), merchants (8), unskilled workmen (4), manufacturers (2), and professional men (2). However, perhaps the most surprising information, to modern audiences, might be the prior education of students here at the normal school. Of 112 students recorded on the table, only 32 had graduated from a high school or academy. Another 40 attended high school without graduating, and 17 had attended either district or grammar schools, evidently without any high school education at all.

At the time, the school had nine faculty members, in addition to four elementary teachers in the training school, and many of them taught a rather eclectic mix of courses. For example, Elvira Carter taught geography, English literature, and algebra; Frances C. Gaylord taught geometry, grammar, history, and composition; and Laura C. Harding was evidently a sort of Renaissance woman, teaching geometry, astronomy, bookkeeping, reading, vocal music, French, and composition. The principal, James C. Greenough, was also a classroom teacher, and his courses consisted of psychology, didactics, civil polity, and rhetoric.

Over the next decade, the school would continue to grow with several new buildings. In 1900, the training school was relocated to a newly-completed building at the corner of Washington and School Streets, on the site of the original 1846 normal school building. With about 650 elementary-aged students, this meant a substantial increase in the size of the training school, and it also opened up space here in the main building on Court Street. Then, in 1903, the school opened a new dormitory, Dickinson Hall. It was located in the rear of the Court Street property, along King Street, and it could house up to 75 students.

The enrollment at the normal school continued to grow in the early 20th century, and by the 1920s it had about 200 students. By this point, a high school diploma was required for admission, and applicants also had to be in good physical condition, at least 16 years of age, and of good moral character. Starting in 1912, only women were admitted to the school, and it would not become coeducational again until 1938. At the time, tuition and textbooks were free for Massachusetts residents, but out-of-state students had to pay $25 per semester, equivalent to about $380 today. Students who lived on campus in Dickinson Hall had to pay $250 per year for room and board, or about $3,800 today.

For most of its early history, the school offered a two-year program for future teachers, but in 1928 it was expanded to three years, and then in 1931 to four years for those who would teach in junior high schools. In 1932, the school was renamed the Westfield State Teachers College, and two years later it began conferring bachelor of science degrees in education. By the early 1940s, though, the school was no longer free for in-state students. Tuition for Massachusetts residents was $75 for the 1941-1942 school year, and $300 for out-of-state students. Textbooks were $35 per year, and a dormitory room was $60 per year, plus about $4.50 per week for meals. In total, an in-state student who lived on campus paid about $300 per year, or nearly $5,300 today.

This building here on Court Street remained in use until 1956, when the growing college moved to its present-day campus on Western Avenue, about two miles to the west of here. It subsequently expanded its programs beyond just training teachers, and it has since gone through several more name changes, becoming the State College at Westfield, Westfield State College, and finally Westfield State University in 2010. Its enrollment has also grown significantly during this time, with nearly 4,900 undergraduate students in 31 different programs.

In the meantime, the old building here on Court Street was sold to the city of Westfield, and it was converted into a new city hall. It replaced an older building on Broad Street, which had been in use by the municipal government since 1837. This project included major renovations to the interior of the old school, but the exterior remained largely unaltered. From this angle, the only visible change to the building was the addition of a brick vault on the right side. It is three stories in height and measures about 16 feet by 17 feet, but it is mostly hidden from view behind the trees in the present-day photo.

The building was renovated at a cost of $150,000, and the work was completed by 1959. Along with housing the city government, the building was also occupied by the Westfield District Court, which was located on the left side. The court later moved into its own facilities, but this building continues to be used as city hall, with hardly any difference in its exterior appearance since the first photo was taken more than 125 years ago. In 1978, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places, and in 2013 it also became a contributing property in the Westfield Center Historic District.