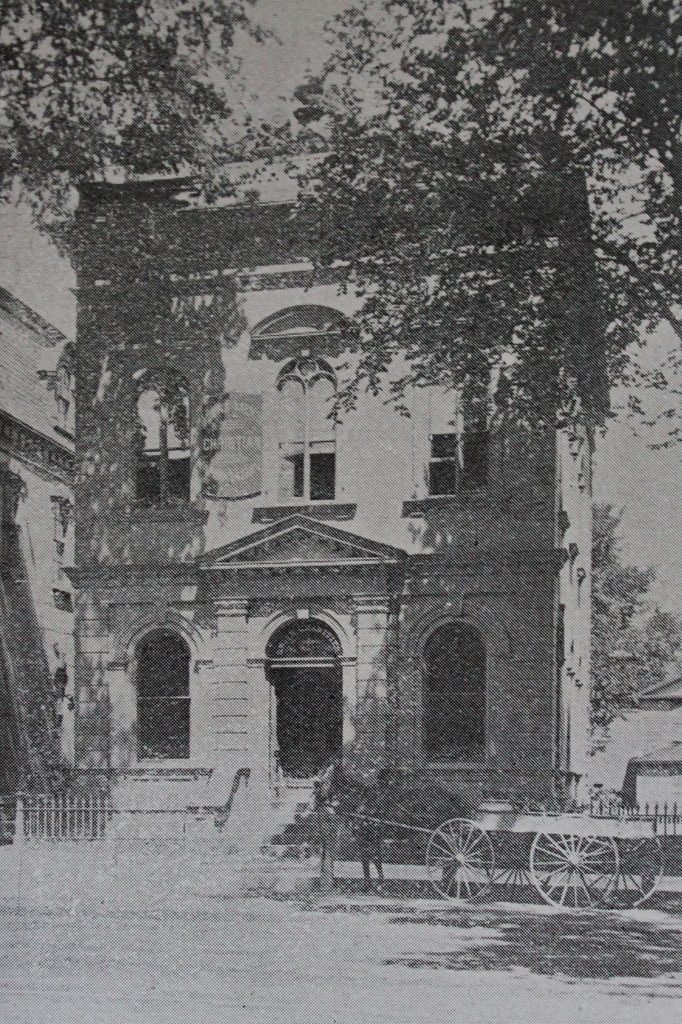

The Nathaniel Parsons House on Bridge Street in Northampton, around 1914. Image from Early Northampton (1914).

The house in 2017:

Northampton has a remarkable collection of colonial-era homes, but one of the oldest is this house on Bridge Street. It has been significantly expanded over the years, but the original part of the house has, at various times, been estimated to be as old as 1658 and as recent as 1730. However, more recent dendrochronological analysis of the home’s timbers has provided an approximate date of 1719 for the oldest section of the house.

This plot of land was originally owned by Joseph Parsons, one of the founders of both Springfield and Northampton. He and his wife Mary came to Northampton in 1655, just a year after the first European settlers arrived, and they would live here for about 25 years. During this time, however, Mary repeatedly faced accusations of witchcraft, brought by members of the Bridgman family. Joseph won a slander suit against the Bridgmans in 1656, but the accusations continued and in 1675 Mary was put on trial for witchcraft. She was ultimately acquitted, but soon after she and Joseph returned to Springfield, where they lived for the remainder of their lives.

Despite this controversy, other members of the Parsons family remained here in Northampton. Their son Jonathan subsequently owned this lot, and apparently built a house here, but the existing house was built by his son Nathaniel, who was born in 1686. Nathaniel married his first wife, Experience Wright, in 1714, but she and their infant child died the following year. He evidently built this house a few years later, but would not remarry until 1728, when he married Abigail Bunce. They had five children together, although two of them, Abigail and Jerusha, were twins who both died soon after they were born. Their other three children all lived to adulthood, and included a daughter, Experience, and two sons, Elisha and Nathaniel.

When built, this house was much smaller. It was only one room deep, and had two rooms on the first floor and two on the second. It would remain this way for most of the 18th century, even as the family continued to grow in size. The older Nathaniel died in 1738, but Abigail outlived him by 50 years and lived here in this house with her children and grandchildren. Experience lived here until her first marriage in 1754, then returned after her husband’s death two years later and lived here until her second marriage in 1768. Elisha lived here until his marriage in 1770, and he may have continued living here as late as 1779, and the younger Nathaniel lived here for the rest of his life, even after his 1768 marriage to Sarah Hunt. For a far more comprehensive account of the house and the people who lived here, see this website.

At some point in the late 18th century the house was finally expanded, with a lean-to on the back that included a new kitchen. Abigail died in 1789, but Nathaniel and Sarah continued to live here, with Nathaniel having purchased his siblings’ shares of the house. They had nine children, although, as was the case with his parents, two were twins who died in infancy. Their other seven children were Nathaniel, Luther, Sally, Abigail, Mary, Persis, and Eunice, and they all grew up here in this house. The two oldest later owned the house, and sold it upon Nathaniel and Abigail’s deaths in 1806 and 1807.

Around 1808, the house was purchased by the Wright family, and was jointly owned by Chloe Wright and her stepson Ferdinand Hunt Wright. The house was further expanded soon after. An ell was added to the house, and the lean-to roof was removed in order to add a second floor above the late 18th century addition. Hunt, as he was known, married Olive Ames in 1811, and they had three children: Elzabeth, Roxana, and Mary. He died in 1842, and by about 1850 Olive had moved out, although she continued to own her half of the house and rented it to George and Lydia Sergeant. In the meantime, Chloe Wright lived in her half of the house until her death in 1854, and her daughter Fannie appears to have lived here until her death in 1869.

The Wright family retained ownership of the house for many years, living here at various times while also renting part of it to tenants. Olive and her daughter Roxana had returned to this house by the 1880s, and both lived here for the rest of their lives, until Olive’s death in 1889 and Roxana’s in 1909. The first photo was probably taken several years later, by which point the house was owned by three of Mary’s children: Anna, Arthur, and Edgar Bliss. Anna, who was unmarried, lived here from 1910 until her death in 1941, and in her will she left the house to Historic Northampton, which continues to own the property today.

More than a century after the first photo was taken, this view of the house has undergone a few minor changes, including the removal of the shutters and the small front porch. These would have been later additions, though, so today the house looks more historically accurate than it did when the first photo was taken. The Parsons House is now one of three owned by Historic Northampton, although it is currently closed to the public for renovations.