The house at the corner of South Street and Bridge Lane in Hatfield, in April 1934. Image taken by Arthur C. Haskell. Library of Congress, Historic American Buildings Survey Collection.

The house in 2024:

This house, which is also referred to in some sources as the Morton House, was built around 1762 by John Dickinson. It is a saltbox-style house, with a second story on the front part of the house and a long, sloping roof in the back. This design was typical for mid-18th century homes in the Connecticut River valley, and the large center chimney was also a common feature from homes of this period. However, this house is probably best known for its elaborate front doorway. Such doorways were often found on higher-end homes in the valley during the mid-18th century, although this one is unusual because it is topped by a rounded pediment, rather than the more common flat-top or scroll pediments.

During the 19th century, the house was owned by the Morton family, with the 1873 county atlas showing an M. Morton here. By the time the top photo was taken in 1934, it was owned by Eugene E. Jubenville. The photo was part of the Historic American Buildings Survey documentation of the house, which also included a series of architectural drawings of the interior. By this point, the exterior of the house had undergone some changes, including the installation of exterior shutters and 2-over-2 windows, but overall it retained much of its 18th century form, including its distinctive doorway.

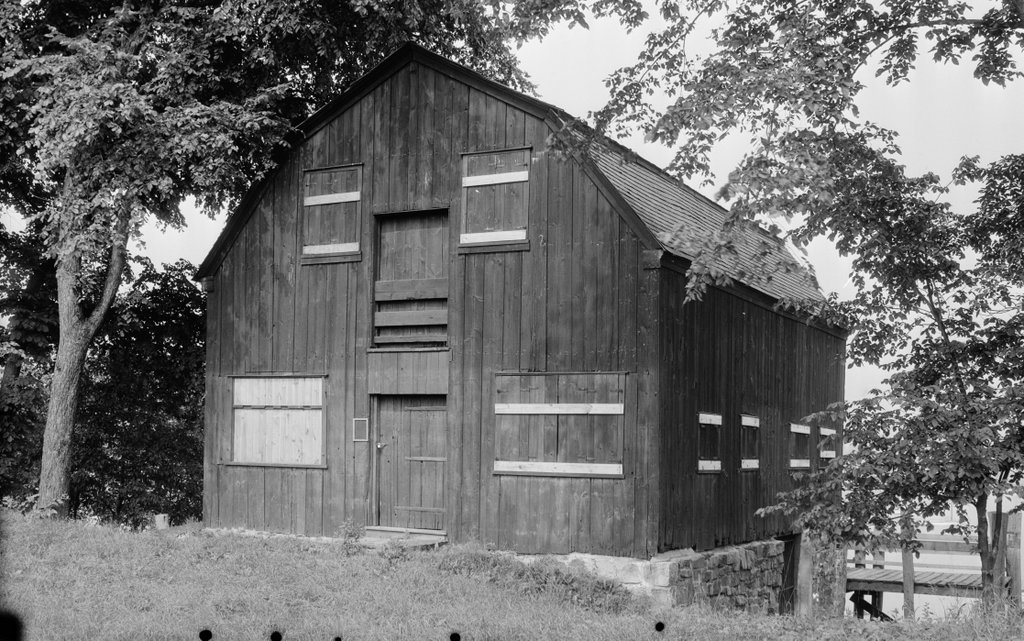

Today, the house is still standing here, as shown in the second photo. There have been some changes, including the loss of the outbuildings and barns behind the house, but otherwise the house itself has seen few changes. In some ways, it even looks more true to its historic appearance now than it did in 1934, due to the removal of the shutters and the installation of 18th century-style 12-over-12 windows. The ornate doorway is also still there, although it is now hidden from this angle by the large hydrangea bush. This plant must be around 100 years old now, because it is also visible in the 1934 photo, back when it was much smaller.