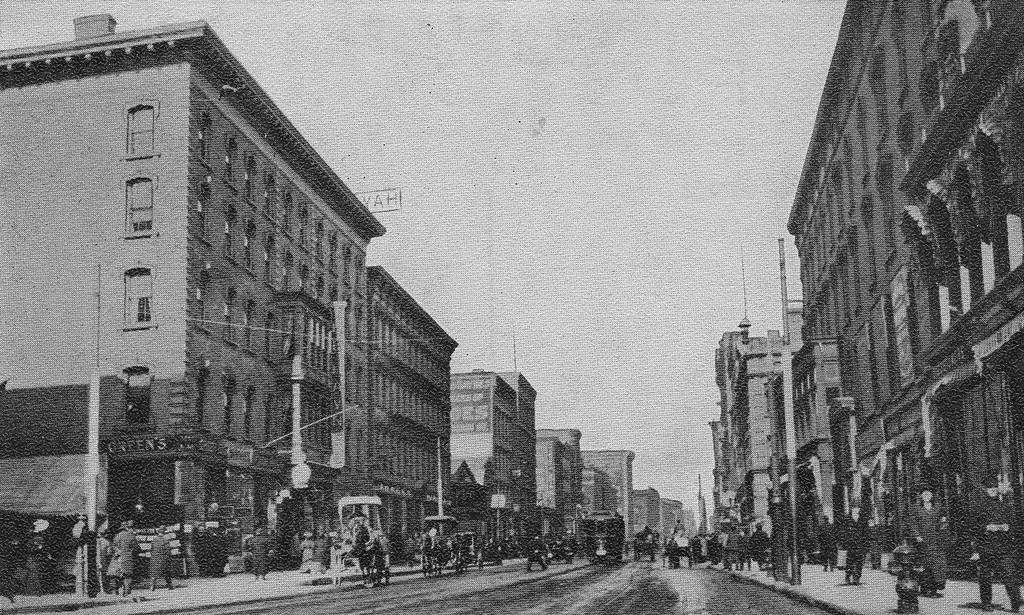

Looking north on Main Street, from near the corner of Elliot Street in Brattleboro, around 1871-1885. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

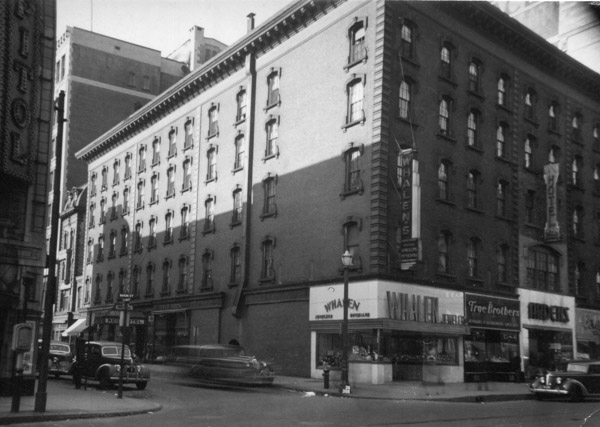

The scene in 2017:

This block, on the west side of Main Street between Elliot and High Streets, was the scene of one of the most disastrous fires in Brattleboro history, which occurred on October 31, 1869. All of the buildings along this section of Main Street, mostly wood-frame stores and hotels, were destroyed in the fire, including the Brattleboro House hotel and several other important commercial blocks. However, the property was quickly redeveloped, and within two years the ruins had been replaced by two large, brick commercial buildings, with the Crosby Block on the left and the Brooks House further in the distance on the right.

The first photo shows the Crosby Block as it appeared within about 15 years of its completion in 1871. It was owned by grain and flour merchant Edward Crosby, and was designed by local architect George A. Hines, whose plans reflected the prevailing Italianate style for commercial buildings of this era. Only about two thirds of the building is visible in this scene, as it was once 26 window bays wide, extending all the way to the corner of Elliot Street. As was often the case in downtown commercial blocks, it was originally a mixed-use building, with stores on the ground floor, professional offices on the second floor, and apartments on the third floor.

Further in the distance, on the right side of the scene, is the Brooks House, which was also known as the Hotel Brooks. Although completed in the same year as the Crosby Block, it featured far more elaborate Second Empire-style architecture that contrasted with the modest design of its neighbor. Designed by noted architect Elbridge Boyden, the hotel was reportedly the country’s largest Second Empire-style building outside of New York City at the time, and was a popular Gilded Age summer resort. It was owned by George Jones Brooks, a merchant who had grown up in the Brattleboro area but later made his fortune in San Francisco, as a merchant during the Gold Rush. However, he later returned to Brattleboro, where he built this hotel and also later founded the Brooks Memorial Library.

More than 130 years after the first photo was taken, this scene has remained remarkably unchanged. The facade of the southernmost section of the Crosby Block, just out of view to the left, was rebuilt in the late 1950s and is now completely unrecognizable from its original appearance. However, the section of the building in this scene has been well-preserved, and still continues to house a variety of shops on its ground floor. On the right side of the scene, the Brooks House is also still standing. The interior was completely rebuilt in the early 1970s and converted into offices and apartments, but the exterior was preserved. More recently, the upper floors were heavily damaged by a fire in 2011, but the building has since been restored and still stands as a major landmark in downtown Brattleboro.