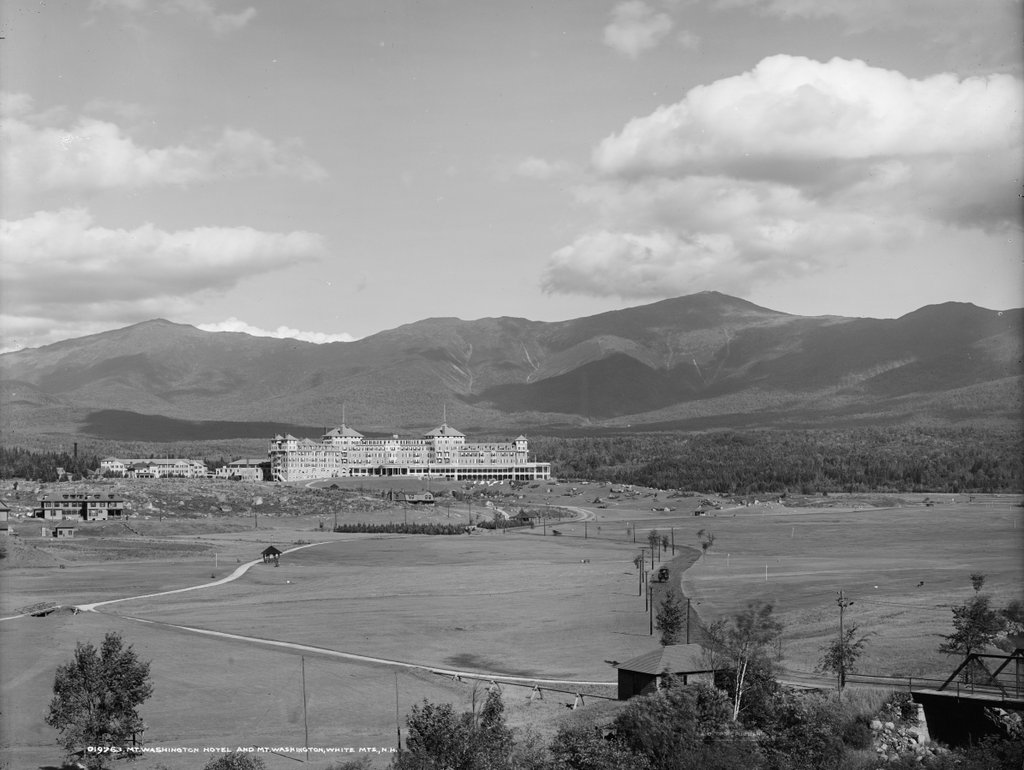

The Mount Washington Hotel, with its namesake mountain behind it in the distance, around 1906. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

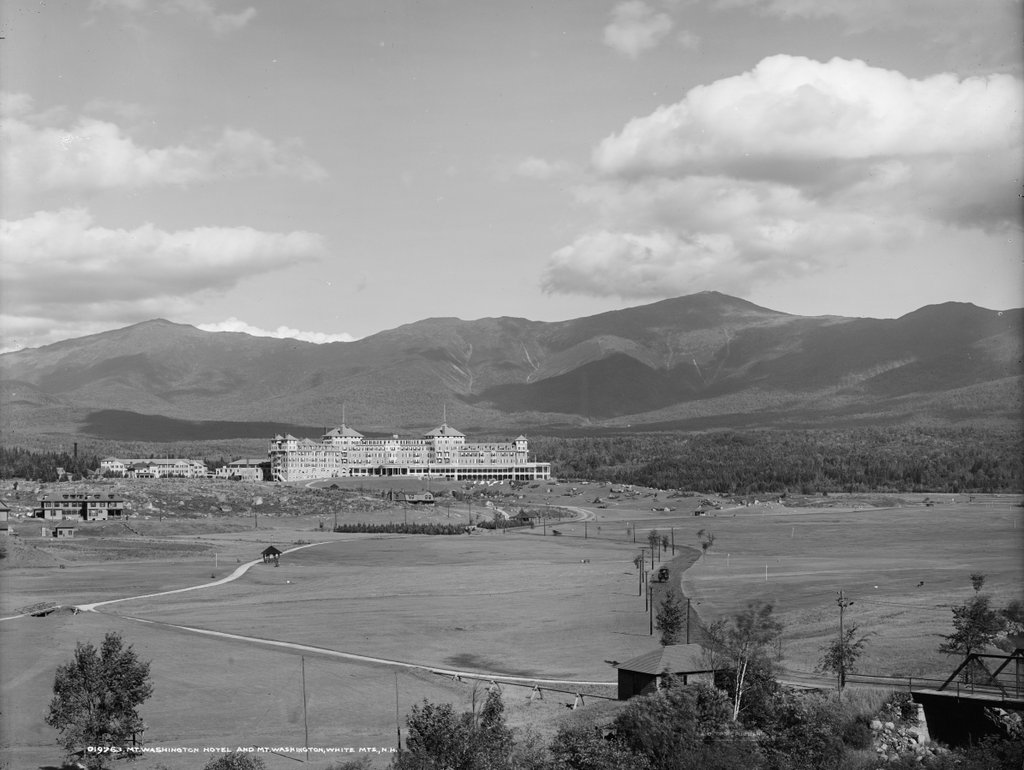

The scene in 2020:

The White Mountains became a popular tourist destination during the second half of the 19th century, and the region featured a number of grand hotels. However, few could match the Mount Washington Hotel, which was built here in the Bretton Woods area of Carroll, New Hampshire between 1900 and 1902. It was owned by Joseph Stickney, a coal tycoon who had been involved in White Mountain hotels since 1881, when he purchased the Mount Pleasant House. Located approximately where these two photos were taken, the Mount Pleasant House started small, but it was subsequently expanded under Stickney’s ownership and became a prosperous hotel.

Around the turn of the century, Stickney decided to build an even larger hotel across the street from the Mount Pleasant House. He hired noted New York architect Charles Alling Gifford, who designed this Spanish Renaissance-style building, as shown in these two photos. It has a Y-shaped footprint, and its most distinctive exterior features are the two large octagonal towers. The hotel was completed in 1902 at a cost of about $2 million, and it formally opened on July 31, with a ball that was attended by dignitaries such as Chester B. Jordan, the governor of New Hampshire.

Upon completion, the hotel had 352 rooms and could accommodate around 600 guests. A night’s stay cost $20, which was a substantial amount of money at the time, and it included the room and three meals. Writing about a month before it opened, the Boston Herald declared it to be “one of the largest and most perfectly appointed resort hotels not only in New England, but in the summer resort world.” The article continued with the following description of the hotel:

It will contain, besides the ordinary accommodations for the comfort of guests, many novel and attractive features. The music room is 115 by 73 feet in size, with a spacious stage at one end to be used for amateur theatricals, and the rotunda, which is 135 by 103 feet, is the largest in any hotel in New England. The octagonal dining room in the northwest wing is 84 by 84 feet, and will seat 500 people. On two sides are spacious galleries, which can be utilized for the orchestra. Every suite has a private bath, and the chambers are all very large.

On the ground floor are the indoor amusements, including billiard rooms, ping-pong tables, golf club quarters, gun room, clubroom, bicycle room, shuffle boards, a large play room for children, and a mammoth swimming pool filled with water from the Ammonoosuc River, and tempered by steam jets to the right warmth. The floor of the pool is tiled, and adjoining are dressing and toilet rooms, with facilities for Turkish baths.

The first photo was taken only a few years after the Mount Washington Hotel opened. It shows the building and grounds from the main road, about a half mile away. In the foreground is the bridge over the Ammonoosuc River and the long driveway to the hotel. In the distance is the hotel’s namesake mountain, Mount Washington, which stands beyond and to the right of the hotel. The summit is about seven miles east of the hotel, and about 4,600 feet higher in elevation. Rising 6,288 feet above sea level, it is the highest mountain in the northeastern United States, and it is flanked by other peaks in the Presidential Range, including Mount Jefferson on the far left and Mount Monroe on the far right.

The Mount Washington Hotel was a popular resort destination throughout the early 20th century, drawing prominent guests such as Woodrow Wilson, Warren Harding, Winston Churchill, Thomas Edison, Mary Pickford, and Babe Ruth. However, the most famous gathering here occurred in July 1944, in the midst of World War II, when 730 delegates from 44 Allied nations met at the Mount Washington Hotel. Known as the Bretton Woods Conference, this meeting was held in anticipation of the end of the war, in order to establish international monetary policies for the postwar world.

The Bretton Woods Conference delegates included many of the world’s leading economists, including Harry Dexter White, John Maynard Keynes, and U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr., who presided over the conference. Among the agreements reached here were the establishment of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, along with policies for currency exchange rates. The conference led to what became known as the Bretton Woods system, which remained the predominant international economic system until the early 1970s.

In the meantime, the mid-20th century was a difficult time for the grand 19th century hotels in the White Mountains. Many succumbed to fire, while others faced a slow, steady decline as the buildings aged and tourist preferences shifted. However, the Mount Washington Hotel managed to avoid the fate of nearly all its contemporaries, and it still stands here nearly 120 years after it opened.

Today, there have been few significant exterior changes to the hotel, and the scene still looks much the same as it did at the turn of the 20th century, although the trees are now much taller and partially hide the building from this spot. Now known as the Omni Mount Washington Resort, it remains one of the premier hotels in the region, and it stands as a rare surviving Gilded Age resort hotel here in New England. Because of its historic significance, particularly with regards to the Bretton Woods Convention, the hotel was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978, and it was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1986.