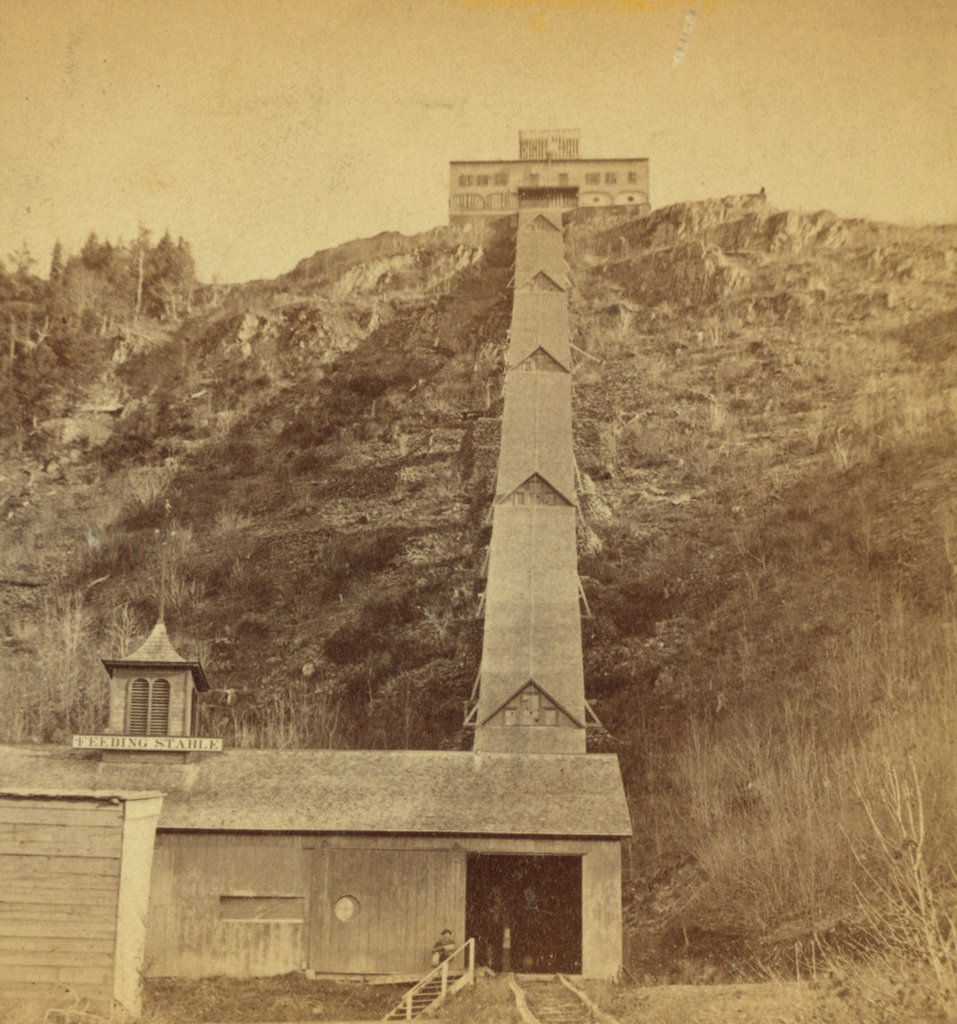

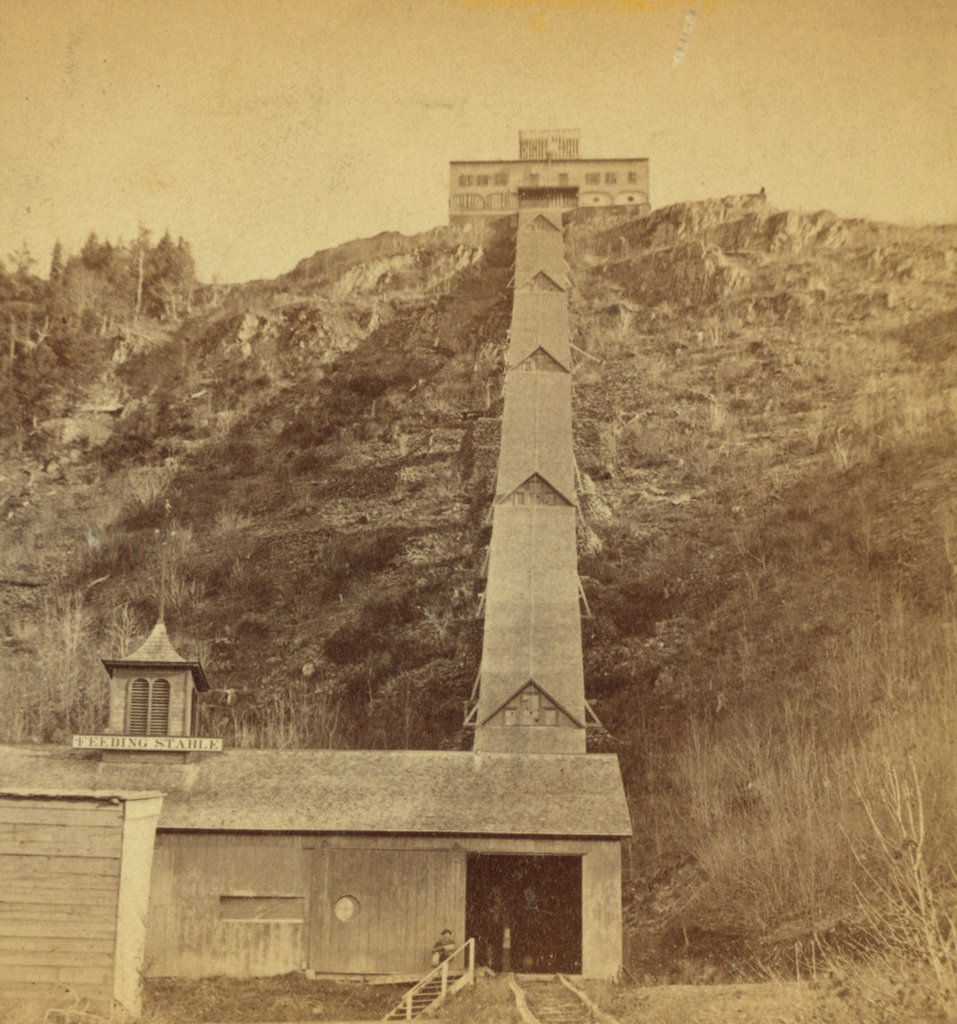

The inclined railway leading up to the Summit House on Mount Holyoke, around 1867 to 1885. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The scene in 2019:

As discussed in the previous post, the summit of Mount Holyoke was the site of one of the first mountaintop hotels in the United States. At just 935 feet in elevation, it is not a particularly tall mountain, yet it rises high above the surrounding landscape in the otherwise low, flat Connecticut River valley. It is part of the Holyoke Range, a narrow ridgeline that runs east to west for about eight miles. This, in turn, is a sub-range within the much longer Metacomet Ridge, a traprock ridge that extends from Long Island Sound in Connecticut to just south of the Massachusetts-Vermont border.

Mount Holyoke is not the highest peak in the Holyoke Range, as it stands nearly 200 feet lower than Mount Norwottuck. However, it forms the western end of the ridge, with the Connecticut River passing through a narrow gap between Mount Holyoke and the Mount Tom Range. This prominent location makes it a major landmark for travelers in the river valley, and it also means that the summit has nearly 360-degree views of the surrounding landscape.

The combination of dramatic views and proximity to large large population centers made Mount Holyoke a popular destination in the 19th century, and the first building at the summit was built in 1821. In the spirit of a traditional barn raising, it was built with the help of nearly 200 townspeople who climbed to the summit to lend a hand. Consuming, as one 19th century account described it, “a little water with a good deal of brandy in it,” the group completed the summit house in just two days. It was a modest structure, measuring just 18 by 24 feet, but it was dedicated with much fanfare, including a speech by Northampton native and U. S. Senator Elijah H. Mills.

This first building was soon joined by a rival establishment nearby, but the two buildings were consolidated under the same ownership in 1825. The business operated here for several more decades, and during this time the view from the top of the mountain was made famous by Thomas Cole’s 1836 painting The Oxbow, long regarded as a masterpiece of 19th century American landscapes.

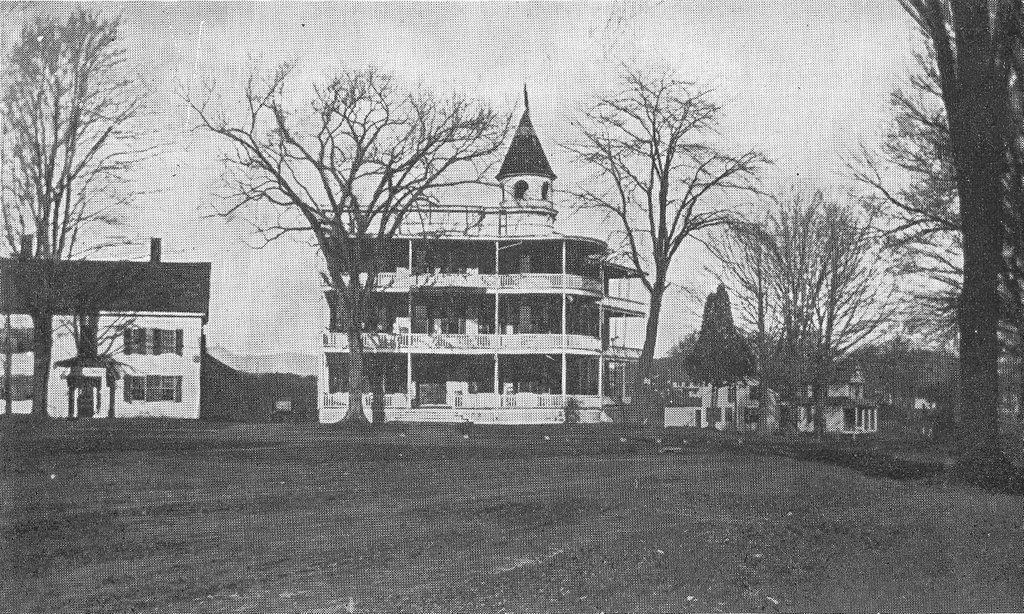

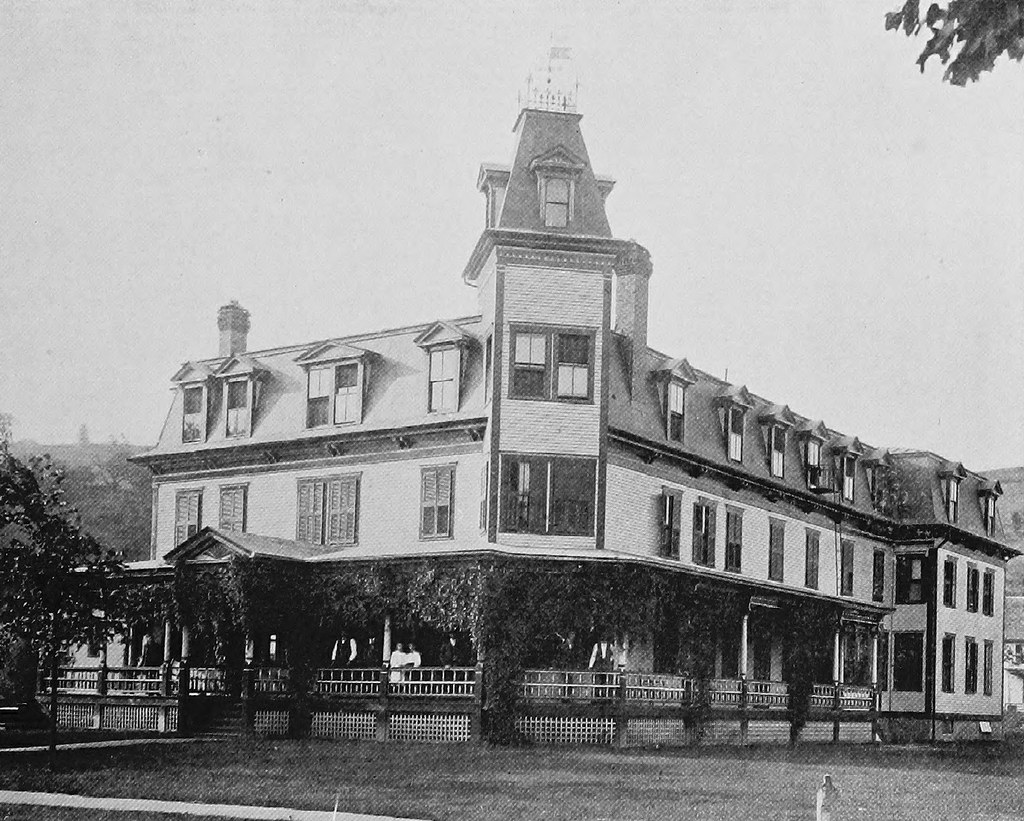

However, despite the mountain’s growing popularity, the accommodations at the summit remained primitive until mid-century. This began to change in 1849, when Northampton bookbinder John French and his wife Frances purchased the property. They soon began making improvements, most significantly a new hotel at the summit, which was completed in 1851. It was named the Prospect House, and it had two stories, with a dining room, sitting room, and office on the first floor, and six guest rooms on the second floor. Above the second floor was a cupola, which was equipped with a telescope. The hotel was later expanded several times, but this original 1851 structure still survives as part of the present-day building.

In addition to constructing a more substantial building, French also improved access to the summit. Prior to his ownership, it was relatively easy to reach the spot where these two photos were taken, whether on foot or by carriage. In terms of elevation, this spot is more than halfway up the mountain, but from here the slope becomes significantly steeper, as is made particularly evident in the first photo. The only options for visitors during the first half of the 19th century were either to take the long, winding, narrow carriage road to the summit, or hike the short but steep path up the mountainside, gaining over 350 feet in elevation in just 600 horizontal feet.

Neither option was ideal for most visitors, and the situation also made it difficult for French to bring supplies up the mountain. Even water had to be either carted or carried up to the summit, requiring him to sell it for around three to five cents per glass, or about $1.00 to $1.50 today. However, in 1854 he solved both problems with the construction of an inclined railway. It began here at this spot, next to French’s residence, which was known as the Halfway House, and it rose to the top of the mountain. It was originally powered by a stationary horse here at the base, although in 1856 French switched to steam power. The railway itself was rebuilt several times, but it had largely assumed its final form by 1867, as shown in the first photo. By then, the railway had two tracks, was completely enclosed, and brought its passengers directly into the basement of the hotel.

In the meantime, the hotel also grew, with the first major addition coming in 1861, when it was expanded to ten rooms. Then, in 1871 French sold the property to South Hadley businessman John Dwight. However, John and Frances French remained here to manage the hotel, and they continued in that role until their deaths in the 1890s. Then, the hotel was expanded even further in 1894, with the addition of a large wing on the south side of the building. This increased the hotel’s capacity to 40 guests, along with a dining room that could seat 200 people.

By then, the hotel had several local competitors on the nearby Mount Tom Range, with the Eyrie House atop Mount Nonotuck, and the Summit House on Mount Tom. However, both of these were plagued by fires, which was a constant danger for wood-frame buildings on isolated mountaintops. The Eyrie House, built in 1861 and later expanded, burned in 1901, and the same fire also destroyed the partially-built structure of what would have been a new hotel. The Summit House on Mount Tom faced similar problems, with the original 1897 one burning in 1900, and its replacement suffering the same fate in 1929.

However, although older than the other nearby summit houses and built of similar materials, the hotel here on Mount Holyoke managed to avoid catastrophic fires. It faced different challenges, though, most significantly the declining popularity of mountaintop hotels in general. John Dwight died in 1903, the property was subsequently acquired by a group of prominent locals, including Holyoke silk manufacturer Joseph Skinner. The new owners made significant improvements, including electricity and modern plumbing. The railway was also electrified, and the first automobile road to the summit opened in 1908.

Skinner would ultimately acquire full ownership of the hotel, and he continued to modernize it throughout the early 20th century. It continued to face challenges though, particularly with the onset of the Great Depression, but the hotel was ultimately closed after the September 1938 hurricane. The older section of the building survived, but the storm destroyed the large 1894 addition. A year later Skinner donated the property to the state, and it became the Joseph Allen Skinner State Park.

Both the hotel and the inclined railway deteriorated after the park was established, and much of the roof over the railway was destroyed in a heavy snowstorm in 1948. The remains of the railway were removed in 1965, and the hotel itself was also threatened with demolition around this time. Despite many years of neglect, though, the building was ultimately restored in the 1980s, and it is now a museum.

Today, nearly all of the historic 19th century mountaintop hotels in the northeast are gone, most having been lost to fire, neglect, or both. However, the Summit House on Mount Holyoke is still standing as one of the few surviving examples. This scene has changed considerably since the first photo was taken around 150 years ago, including the loss of the railway and the significant tree growth on the previously bare slopes, but the Summit House is still visible from this spot.