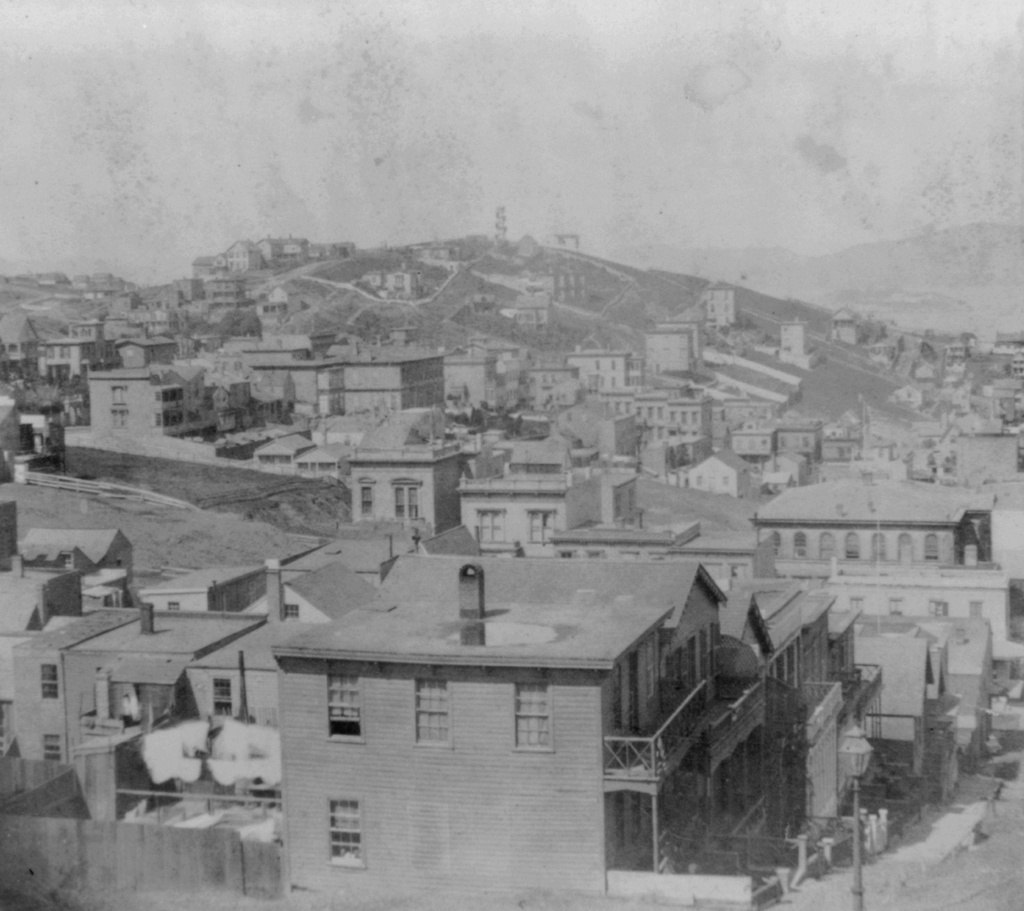

The view of Russian Hill from the corner of Mason and Sacramento Streets in San Francisco, around 1866. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Lawrence & Houseworth Collection.

The view in 2015:

Today, Russian Hill is probably best known for the zigzag section of Lombard Street between Hyde and Leavenworth Streets, and its excellent views of the city, as seen in this earlier post, also make it one of the San Francisco’s most expensive neighborhoods. However, when the first photo was taken 150 years ago, it was still sparsely populated, mostly with poorer residents who could not afford to live in a more convenient location. This began to change, though, soon after the photo was taken. Cable cars were introduced to San Francisco in 1873, allowing residents to easily move up and down the city’s many hills. As a result, wealthy residents who no longer had to worry about walking up the steep grades now found Russian Hill and nearby Nob Hill, where these photos were taken from, as appealing places to live.

As is the case with most of the other 19th century views of the city, most of this scene was completely destroyed by the fires caused by the 1906 earthquake. Much of Russian Hill now consists of modern condominium buildings, but there are a few surviving pre-earthquake homes near the top of the hill, especially along Green Street. At least one of these, the Feusier Octagonal House, was standing when the first photo was taken. It was built in the 1850s with an unusual octagonal design, and although the photo isn’t clear enough to identify the house, it would be located somewhere near the top of the hill on the left side.

This post is part of a series of photos that I took in California this past winter. Click here to see the other posts in the “Lost New England Goes West” series.