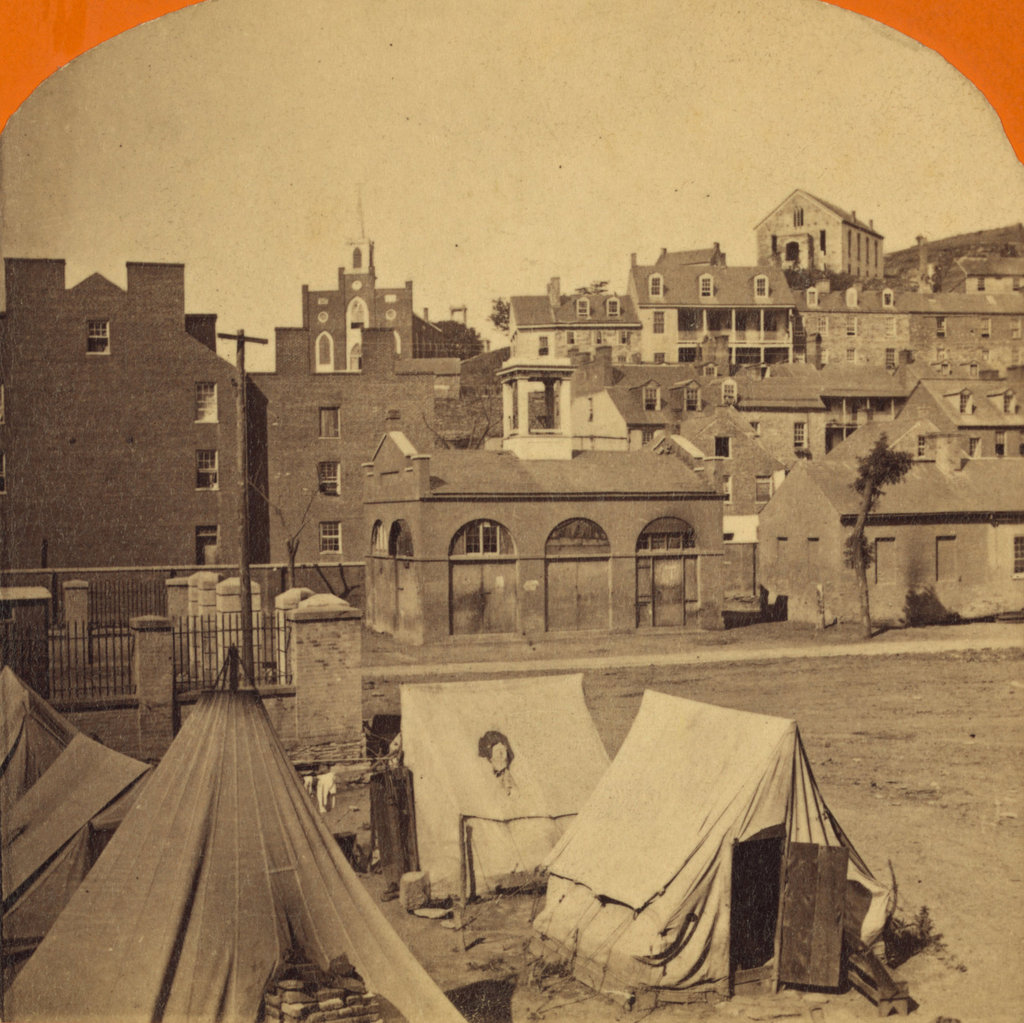

The Hall of Justice at Portsmouth Square in San Francisco, shortly after the April 18, 1906 earthquake. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2015:

When the 1906 earthquake hit San Francisco, the Hall of Justice building was just ten years old. Despite what the first photo shows, it actually survived the earthquake itself. It had been seriously damaged, but neither the building nor the 77 prisoners housed on the upper floors were in any immediate danger. In fact, on the first day of the disaster the mayor made the Hall of Justice his temporary headquarters, since City Hall had been completely destroyed.

However, the situation here soon deteriorated. The earthquake had started a number of fires throughout the city, and a series of poor decisions on the part of city officials allowed the fires to spread. One of the ill-fated tactics was to attempt to create firebreaks by destroying buildings. In most cases, though, this was counterproductive, because the explosives tended to do a better job of igniting the buildings rather than destroying them, which only exacerbated the problem.

By nightfall on the first day, the fire was approaching Portsmouth Square, and the Hall of Justice was hastily evacuated. The prisoners were transported to another prison, and the bodies in the morgue and the police records were removed from the building and piled up in the middle of the square, covered in canvas. As the city burned around the square that night, two police officers guarded the pile. There was virtually no water available for firefighting, so the officers emptied bottles of beer onto the canvas to keep it damp, thus saving both the corpses and the records.

The first photo shows Portsmouth Square perhaps a week or so after the fire. By then the bodies and the police records had presumably been moved to a safer location, and the square was instead covered with tents of displaced residents. The burned-out remains of the Hall of Justice loom in the background, with the frame of the cupola dangling from the top of the building. It was beyond saving, and was demolished soon after. Its replacement was completed in 1910 on the same spot, and it stood here until it was demolished in 1968 to build the 27-story hotel that now stands here. Today, the only thing left from the first photo is Portsmouth Square itself, which is a major focal point within the city’s Chinatown neighborhood.

This post is part of a series of photos that I took in California this past winter. Click here to see the other posts in the “Lost New England Goes West” series.