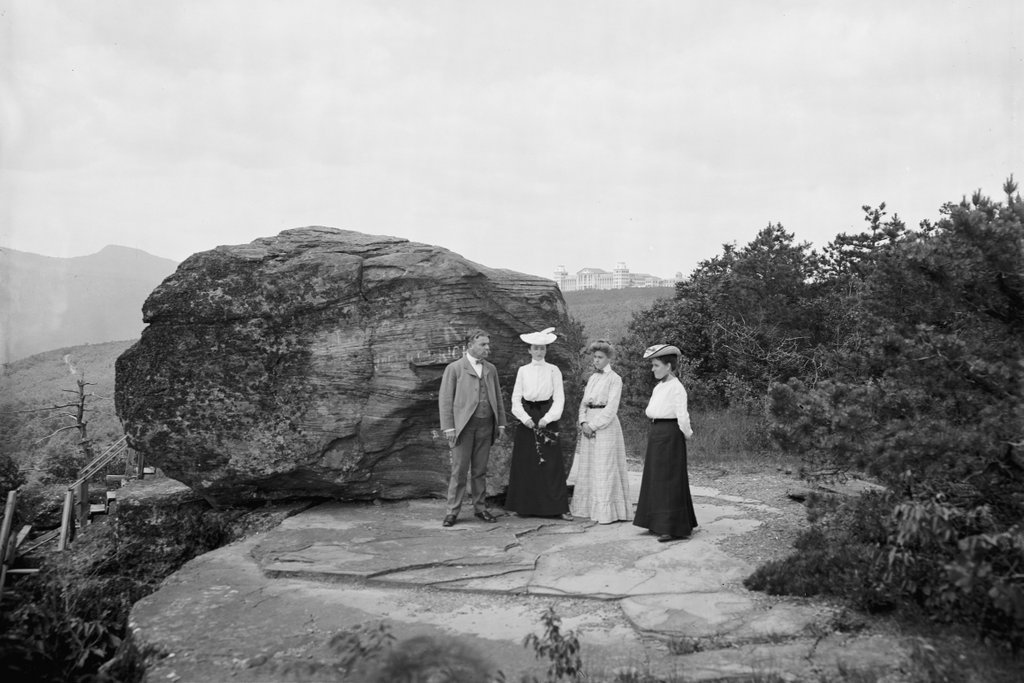

The front entrance of the Hotel Kaaterskill on South Mountain, around 1900-1905. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2021:

The second half of the 19th century was the heyday of mountaintop hotels in the northeastern United States. The Romanticism movement, particularly the paintings of artists like Thomas Cole, had helped to generate interest in the region’s various mountain ranges, which had previously been viewed merely as unimprovable land or as hostile wilderness. At first, these hotels were generally located in accessible and relatively low-elevation mountains, including here in the Catskills and on Mount Holyoke in Massachusetts. However, by the post-Civil War era, they could be found on many of the higher mountains, including New Hampshire’s Mount Washington, the highest peak in the northeast. The quality of these hotels also varied significantly, from small, spartan bunkhouses to grand Gilded Age resorts.

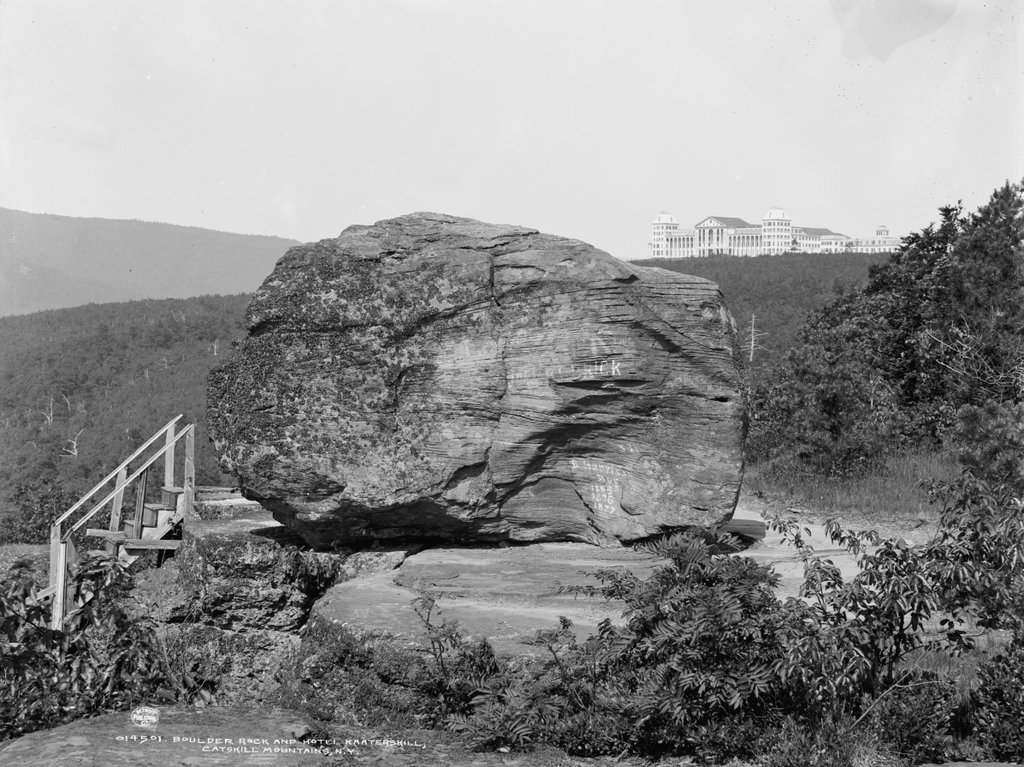

Here in the Catskills, there were several establishments that would have fit in the latter category, but by far the largest of these was the Hotel Kaaterskill, shown here in the first photo around the turn of the 20th century. Opened in 1881, the Kaaterskill was not one of the early mountaintop hotels, nor was it at a particularly high elevation at 2,500 feet. However, it was certainly one of the grandest, and with 1,200 guest rooms it is said to have been the largest mountaintop hotel, not just in the northeast but in the entire world, in addition to supposedly being the largest wood-frame hotel of any kind in the world.

Despite its size and opulence, perhaps the most famous attribute of the Hotel Kaaterskill is the story surrounding its construction. The exact details tend to be muddled in the different versions of this oft-repeated story, but it centers on George Harding, a wealthy Philadelphia parent lawyer who was vacationing at the Catskill Mountain House during the summer of 1880. His daughter (or by some accounts, his wife) was in poor health and had dietary restrictions, so at one meal (some say breakfast, others say dinner) he asked for broiled chicken (or chicken broth, or fried chicken) for her. The kitchen refused to accommodate the request since it was not on the menu, and Harding subsequently had an argument with the hotel owner, Charles Beach, who suggested something to the effect that, if he wanted chicken so badly, he could build his own hotel and serve chicken there.

Regardless of the exact details of this confrontation, the result was that Harding almost immediately set out to build a hotel that would rival the Mountain House in every way. By September he had selected the site here on South Mountain, and workers broke ground for the new building. He employed some 700 workers throughout the winter, not only building the hotel but also laying out a road up the steep Catskill Escarpment, connecting the village of Palenville to the hotel. The hotel was designed by prominent Philadelphia architect Stephen Decatur Button, and it was four stories in height, with a long piazza here on the southeast side. As shown in the first photo, the front entrance featured a massive portico, and the hotel also had towers on the corners of the main façade. It would take several years to complete the hotel, but it was finished enough that Harding was able to open about 600 guest rooms in time for the 1881 summer season.

Building this hotel, especially in such a short time, required a vast amount of money. Contemporary newspapers had differing estimates but it appears to have cost around $1 million, or nearly $30 million today. However, this was no issue for Harding, who had earned a considerable fortune as one of the nation’s leading patent attorneys of his era. Among his early clients was Samuel F. B. Morse, whom he successfully represented in a patent infringement case. Then, in the late 1850s he worked on a case alongside future Attorney General and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, defending against a lawsuit from mechanical reaper inventor Cyrus McCormick. This powerful legal team was also joined by a relatively obscure Illinois attorney named Abraham Lincoln, who acted as local counsel on the case. However Harding and Stanton both looked down upon the provincial Lincoln, and he played little role in the trial, leaving him somewhat embittered by the experience, although Lincoln would ultimately appoint Stanton as his Secretary of War.

Aside from this experience with Lincoln, George Harding had many other political connections, and the Hotel Kaaterskill saw a number of prominent guests, including at least two presidents. Ulysses S. Grant visited the hotel during the summer of 1883, and he was planning on making another visit in August 1885, despite his declining health. However, he died of throat cancer at a cottage in the Adirondacks on July 23, a little over a week before he was supposed to arrive here at the Hotel Kaaterskill.

The other president who visited the hotel during this period was Chester A. Arthur. For a week in August 1884, it became the summer White House, with the president spending a vacation here accompanied by his daughter Nellie, his niece and de facto First Lady Mary McIlroy, and political ally General George H. Sharpe. The president and Harding took daily drives together, and Harding showed him many of the area’s scenic views and other points of interest. He also held a banquet for Arthur, which Harding and his family attended along with a variety of other distinguished guests, including Chief Justice Morrison Waite of the United States Supreme Court. Over the course of the week, other prominent visitors came here to meet with Arthur, including Secretary of State Frederick T. Frelinghuysen and former Supreme Court Justice William Strong.

In 1886, the New York Times published a lengthy article on the Hotel Kaaterskill, which included the following description:

The Hotel Kaaterskill is a city in itself. It has a fine broad front with a tower on each side, and an ample veranda with tall columns running clear to the roof. Two years ago the hotel was found to be too small, and an addition was put up a little to the north of the main building. This is as big as an ordinary hotel. The house as it now stands will accommodate about 1,200 people. This seems to be an exceedingly large number, but in August last year there were nearly 1,100 persons in the house for two weeks. They were not crowded, however, for the hotel has 648 sleeping rooms, and every one of them is surprisingly large and deliciously airy. No hotel can offer more cool, comfortable, and roomy sleeping apartments than this one, and they are furnished excellently. Mountain climbing is apt to tire people, but if they cannot rest on the beds of the Hotel Kaaterskill they cannot rest anywhere in this world. The mattresses are so soft and elastic that people are tempted to lie down during the day just for the sake of the comfort offered by the beds.

In a wing of the house running back there are a large number of unusually well appointed rooms, which are rented to families that come up for the season. There are people who have occupied the same rooms in this part of the house for five consecutive years. The corridors that lead to the rooms are remarkably wide and commodious all through the house. They run all the way around the building on every floor and act as conduits for the cool mountain air, keeping the sleeping apartments at a delightful temperature. The dining room is on the ground floor, immediately behind the office. It is a large and handsome room and has seated 712 people. It will accommodate as the tables are now arranged, with plenty of space to spare, 650 persons. . . .

The servants of the house have their own kitchen and their own dining rooms. Each department of servants has a separate dining room. There are five of these in all. By keeping the different departments separate the excellent system of the house is preserved. The servants’ apartments are near their dining rooms. There is also a separate eating apartment for nurses and children, and a very pretty and well attended place it is. There is a good billiard room in the hotel. There are also four bowling alleys and a bar. The house has its own theater, too; that is, it has what is called the Opera Hall, where concerts and entertainments are given, and where church services are held on Sunday. The hotel has also its own printing office, which looks not unlike the home of some promising country paper. Here the menus and such other printing as the hotel requires are prepared.

The Hotel Kaaterskill remained a popular destination over the next few decades, and Harding owned the hotel until his death in 1902. Harding continued to develop the property over the years, and by the mid-1890s the grounds around the hotel featured a variety of recreational facilities, including a gymnasium, a golf course, tennis courts, and baseball and cricket fields. In addition, the hotel hosted events such as concerts and balls that drew hundreds of attendees to the mountaintop. As was the case for the other major Catskill resorts, the operating season was relatively short, usually running from the end of June until the beginning of September. Room rates during the 1890s started at $21 per week, equivalent to about $700 today, and the hotel also offered special weekend packages that included round trip rail fare from New York City and a three-night stay at the Kaaterskill for $15.

The first photo was taken around the turn of the 20th century. The hotel was still drawing plenty of visitors by this point, but its demographics were starting to change. Around this time, the Catskills were starting to become popular among Jewish residents of New York City. The region had long been the domain of affluent Protestants, but by the turn of the century there were several Jewish-owned hotels in what would come to be known as the “Borscht Belt.” The more established hotels like the Mountain House and the Kaaterskill also saw a number of Jewish guests, a change that is evident in guest lists that were published in newspapers of the period. In the 1880s and 1890s, these lists were primarily comprised of Anglo-Saxon surnames, but by 1910 the vast majority of the guests here had Jewish names.

In 1922, the Hotel Kaaterskill came under Jewish ownership when Harry Tannenbaum of Lakewood, New Jersey purchased the property. It sold for $100,000, a mere fraction of what George Harding had spent to construct it some 40 years earlier, but by this point the Kaaterskill was showing its age. At the time of the purchase, Tannenbaum estimated that it would cost an additional $200,000 to renovate the hotel, which would include modern amenities such as electricity and running water. He worked on these improvements throughout the spring of 1922, and in the fall the journal New York Hotel Review published an article about the Kaaterskill, which included a description of the extensive work that occurred here:

Tons of paint were carted atop the Kaaterskill peak. Equally as much glass soon followed. An army of mechanics: painters, plumbers, glaziers, electricians and linemen, swarmed the old hotel buildings and grounds from early in April until late in May. Marvelous transformation! Electric lights, telephones, hot and cold running water, modern baths, newly carpeted halls, modern, sanitary bedding, furniture and interior room decorations, began to appear where none existed before in the old, cob-webbed corridors and rooms. A magnificent lobby, with broad, inviting stair cases, a beautiful ladies’ parlor, lounge rooms, card rooms, bowling alleys, moving picture hall, and a grand ball-room, capable of accommodating comfortably over 800 persons, and one of the finest, most brilliantly appointed dining-rooms, seating 1,000 diners, presented an aggregation of comforts of which few hotels in the northern part of the state could boast.

The newly-renovated hotel opened for business on Memorial Day weekend, and the article indicated that Tannenbaum’s first season was a success, despite unfavorable weather throughout much of the summer. The future seemed promising for the Kaaterskill, and it opened again during the summers of 1923 and 1924. As it turned out, however, 1924 would prove to be its final season. The hotel closed after Labor Day weekend, but many of the employees were still here a week later, including some who were making soap in the kitchen on the evening of September 8.

During this soap-making process, a fire broke out, and it soon spread from the kitchen to the rest of the hotel. The building’s wood-frame construction, combined with its isolated mountaintop location, allowed the fire to spread throughout the hotel, and by the time firefighters arrived there was little that they could do. The fire burned throughout the night, where it could reportedly be seen from as far away as Massachusetts, and by the next morning there was nothing left but smoldering ruins.

The fire caused an estimated $250,000 in damage, only half of which was insured. The hotel was never rebuilt, in part because by this point the era of grand mountaintop hotels had passed. With widespread car ownership, tourists were no longer limited to places that were accessible by rail, and vacation trends shifted away from the once-popular Gilded Age resorts. The Great Depression, which started only a few years after the Kaaterskill burned, did not help matters, and most of the mountaintop hotels in the northeast had closed by the start of World War II. Among these was the Kaaterskill’s former rival, the Catskill Mountain House, which experienced a steady decline before closing for the last time in 1941. It was likewise destroyed by a fire, in 1963, although this was deliberately started by the state in order to dispose of the badly-deteriorated structure.

Today, the former Hotel Kaaterskill property is now owned by the state of New York as part of the Catskill Park. This site here has been largely undisturbed since the fire, although as the second photo shows there is surprisingly little left from what had once been the world’s largest mountain hotel. The row of stones near the foreground appears to mark the site of the retaining wall from the first photo, and further in the distance is the foundation of the hotel itself, which is mostly hidden from this angle. When seen in person, the foundation gives some indication of the size of the building’s footprint, but it is otherwise unimpressive, looking more like a typical stone wall than the ruins of a grand hotel. Within and around the foundation, there is an assortment of rusted metal and shards of broken glass and pottery, but otherwise there are few visible remnants of the massive building that stood here in the first photo.