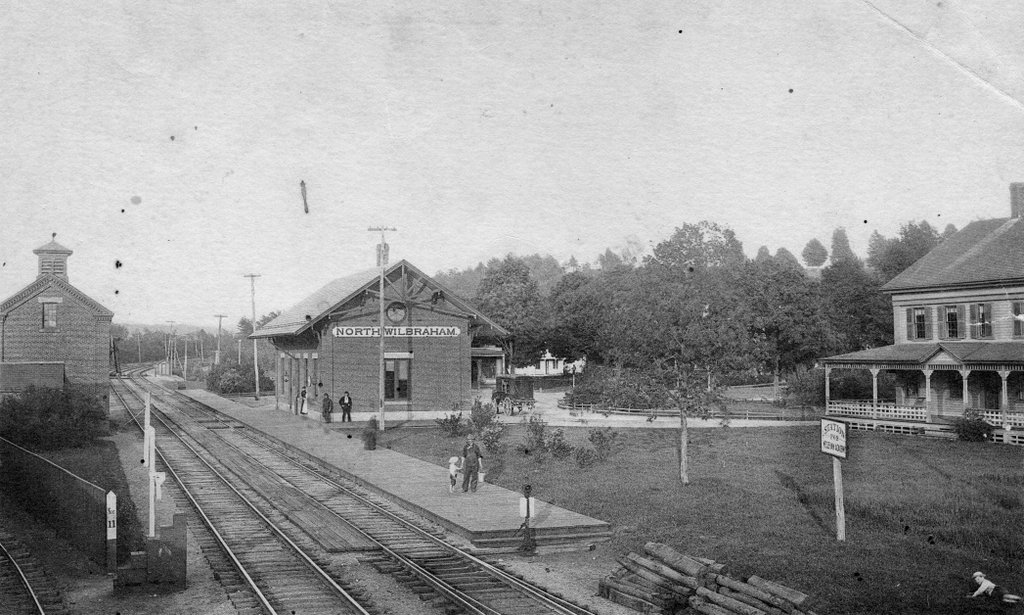

Union Station in Palmer, around 1900-1906. Image from the postcard collection of H. Gray, Springfield, Massachusetts.

The scene in 2020:

Palmer is sometimes referred to as the “Town of Seven Railroads,” and although two of these railroads were never actually operated, the town was and still is a major regional railroad center. The two most prominent of the seven railroads were the Boston & Albany, which ran east-west between those two cities, and the Central Vermont which ran north-south from the Canadian border in Vermont to New London, Connecticut.

These two railroads shared Union Station, with the Central Vermont platform on the left and the Boston & Albany one on the right from this perspective. It was built in 1883, and although Palmer is a relatively small town, its station was designed by Henry Hobson Richardson. One of the most prominent and influential architects in American history, Richardson’s other works in Massachusetts included Trinity Church in Boston, First Baptist Church in Boston, the Hampden County Courthouse in Springfield, and the Church of the Unity in Springfield. However, he was also commissioned by the Boston & Albany Railroad to design their railroad stations. He ended up designing nine stations, including this one, before his death in 1886. After his death, his successors at Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge designed about 20 more stations based on his style, including the old Union Station in Springfield.

Because of its location as a transfer point between north-south and east-west trains, Palmer was an important stop on the Boston & Albany Railroad; an 1885 timetable shows it as one of just seven express stops along the 200 miles between Boston and Albany. It was also the primary rail line connecting Boston to the Midwest, and the 1885 timetable shows connecting trains from Palmer to destinations like Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, Cincinnati, and St. Louis. By comparison, the Central Vermont Railway was a much less prominent, but it was still one of the major north-south railroads in central and western New England, and Palmer became its primary rail hub south of Brattleboro, Vermont.

Passenger rail entered a steady decline in ridership after World War II, with automobiles replacing trains for short trips and airplanes becoming a legitimate alternative for long-distance travel. Many small-town stations closed by the 1950s, including nearby stations in Monson and Wilbraham. However, Palmer remained a stop on the Penn Central Railroad until 1971, when Amtrak absorbed all U.S. passenger rail service and closed Palmer’s station.

Almost 45 years after the last train picked up passengers in Palmer, the historic Union Station is still standing today. Palmer is still a major railroad hub, although now it is exclusively freight trains that stop here. The old Boston & Albany line is now operated by CSX, one of the largest railroads in the country, and the Central Vermont is now operated by the New England Central Railroad, whose southern division offices are still here in Palmer, just a little left of where the photo was taken. A third railroad, the Massachusetts Central Railroad, also operates out of Palmer, and the station is at the southern end of their line.

Despite several decades of deterioration and neglect, the station is still standing. It has since been restored, and the only major difference to the exterior has been the removal of the covered platform on the Boston & Albany side of the building. Otherwise, the rest of the station still reflects its 19th century appearance, and it is now the home of the Steaming Tender restaurant. Because of the busy rail traffic, it is also a popular place for railroad enthusiasts to watch and photograph the passing trains, and the railroad-themed restaurant serves many of these visitors. The restaurant also has a historic locomotive on display, as seen in the foreground of the 2020 photo, and a 1909 passenger car to the left, which is rented for private events.