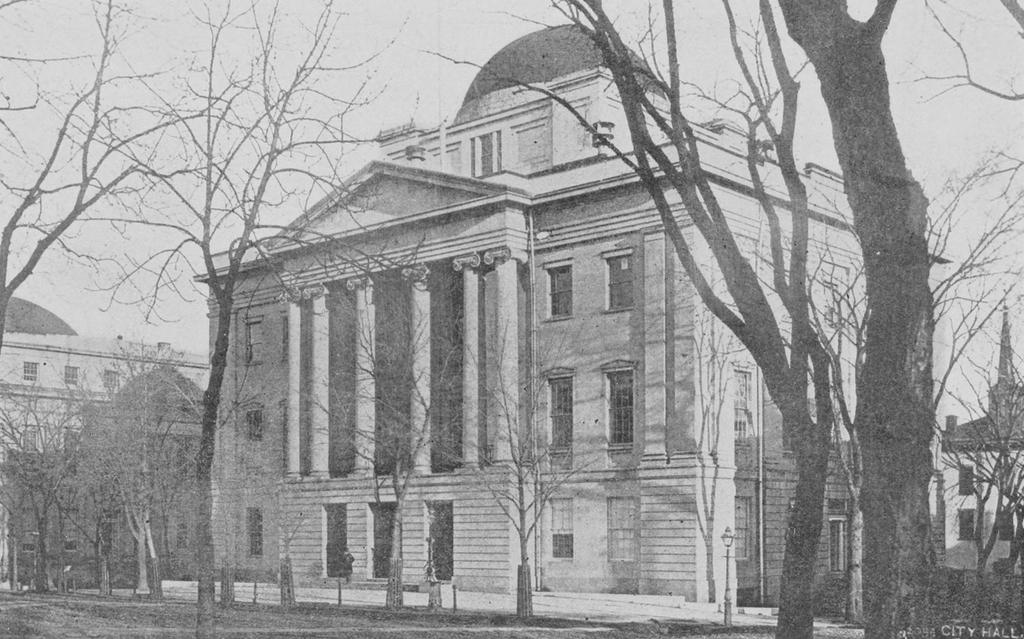

City Hall on Eagle Street in Albany, around the 1860s or 1870s. Image from Albany Chronicles (1906).

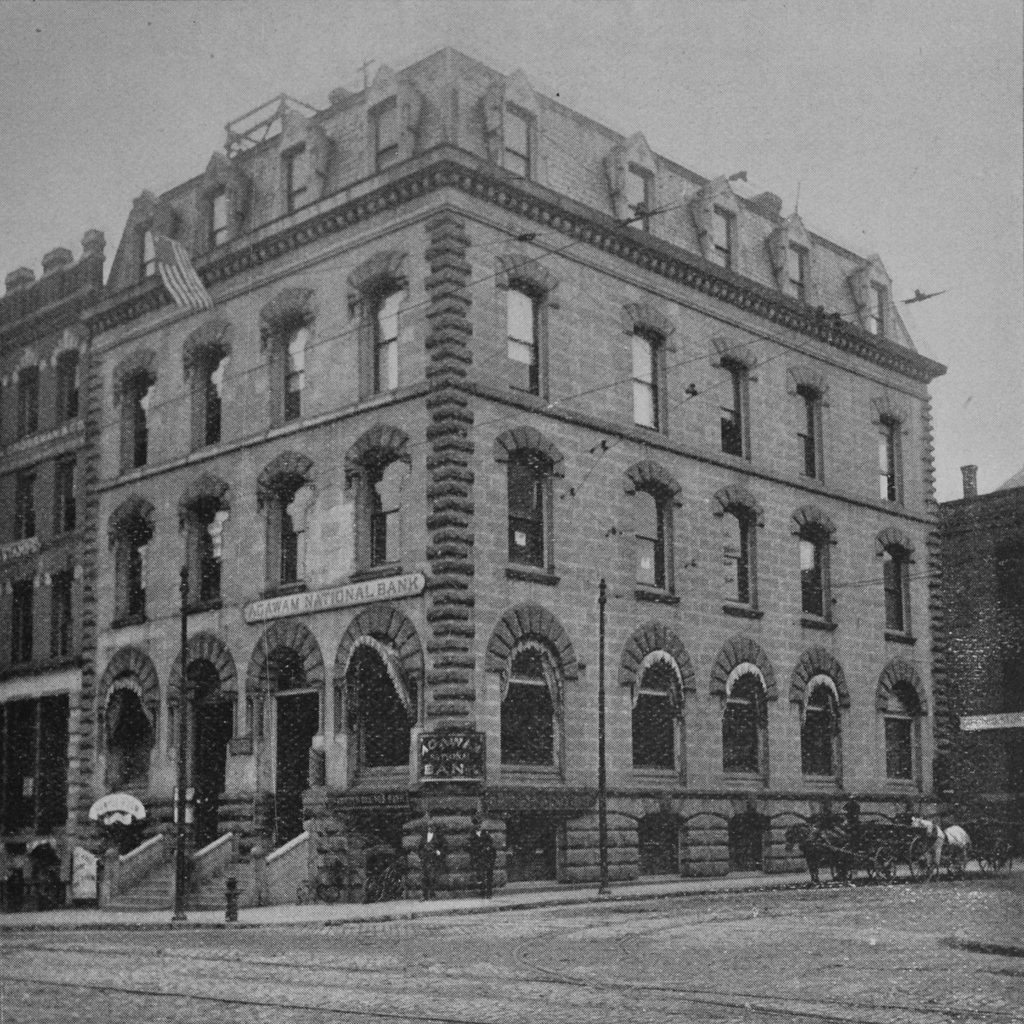

The scene around 1900, with a new City Hall. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

City Hall in 2019:

Albany is one of the oldest cities in the United States, and over the years its municipal government has occupied several different buildings, starting with the Stadt Huys in the 17th century. Dutch for city hall, this name—and building— survived long after the English took control of the former Dutch colony. A new Stadt Huys was built in 1740, and it remained in use until the early 19th century. It also temporarily functioned as the state capitol, from 1797 until Albany’s first purpose-built capitol was completed in 1809.

The city government followed the state government to the new building, and for several decades it served as both the state capitol and as city hall. However, its small size soon became inadequate for the two governments, and in 1832 the city built a new City Hall nearby, on the east side of Eagle Street roughly diagonal to the capitol. The building, which is shown in the first photo here, was designed by prominent local architect Philip Hooker. The exterior was built of white marble, and it featured a Greek Revival design, with Ionic columns supporting the pediment above the front entrance and a dome at the top of the building. It was one of Hooker’s last commissions, and was completed just four years before his death. Over the course of his long career he designed a number of important buildings in Albany, including the First Church, the 1809 capitol, and the Albany Academy, which stands across the street from here.

This City Hall remained in use for nearly a half century, but it was ultimately destroyed in a fire on February 10, 1880. The city subsequently hired famed architect Henry H. Richardson to build a new City Hall here on the same spot. Richardson was, at the time, also involved in the construction of the new state capitol building. He was one of several architects who worked on the capitol over the span of 31 years, and its final design reflected this mix of styles. However, his design for City Hall was entirely his own, and it stands as an excellent example of the Richardsonian Romanesque style that he pioneered.

Thanks to Richardson’s influence, Romanesque architecture was popular for public buildings during the 1880s, and City Hall includes many of the style’s typical features. These include narrow windows, rounded arches above the windows and entryway, asymmetrical facades with a tower in the corner, and a rusticated exterior with contrasting light and dark-colored stones. The majority of City Hall’s exterior is granite from Milford, Massachusetts, and the trim is brownstone from East Longmeadow, Massachusetts, which was one of Richardson’s preferred building materials. Overall, the most distinctive feature of city hall is the 202-foot tower, which rises above the southwest corner of the building. Although Romanesque in its appearance, some architectural historians have viewed the tower as an early hint of modern architecture, with its emphasis on vertical lines.

The new building was completed in 1883, and it is shown in the second photo a few decades later, around the turn of the 20th century. The photo was taken from the grounds of the recently-finished state capitol, presumably from one of the walkways, since the sign in the foreground warns pedestrians to keep off the grass. On the far left side of the photo is State Hall, a state office building that was built in 1842. It is also visible in the first photo, and its Greek Revival design echoes that of the old City Hall. On the far right side of the photo, opposite Maiden Lane (now Corning Place), is a four-story brick commercial block that was likely built around the 1860s or 1870s.

Today, more than a century after the second photo was taken, very little has changed in this scene. City Hall is still standing with few exterior alterations, and it is still in use by the city government. From this angle, perhaps the only noticeable difference is near the top of the tower, where clock faces were added around the 1920s. The neighboring buildings on either side of the photo are also still standing today, although State Hall was extensively renovated in the early 20th century and is now occupied by the New York Court of Appeals, the highest court in the state. Because of their historical and architectural significance, both this building and City Hall were added to the National Register of Historic Places, in 1971 and 1972 respectively.