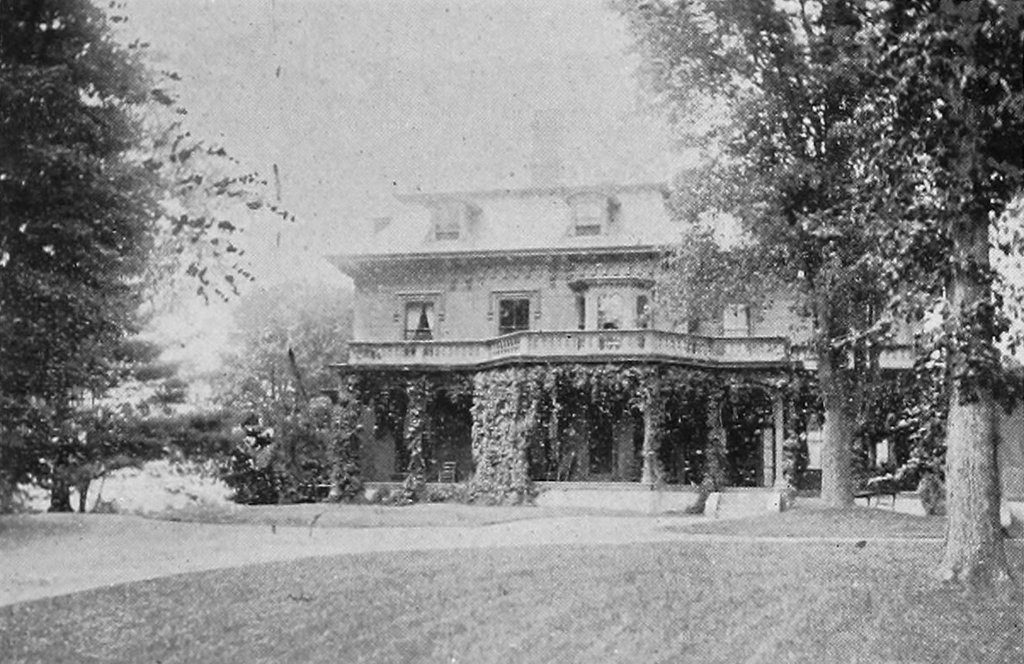

The Wesselhoeft Water Cure, at the corner of Elliot and Church Streets in Brattleboro, probably around the 1860s. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

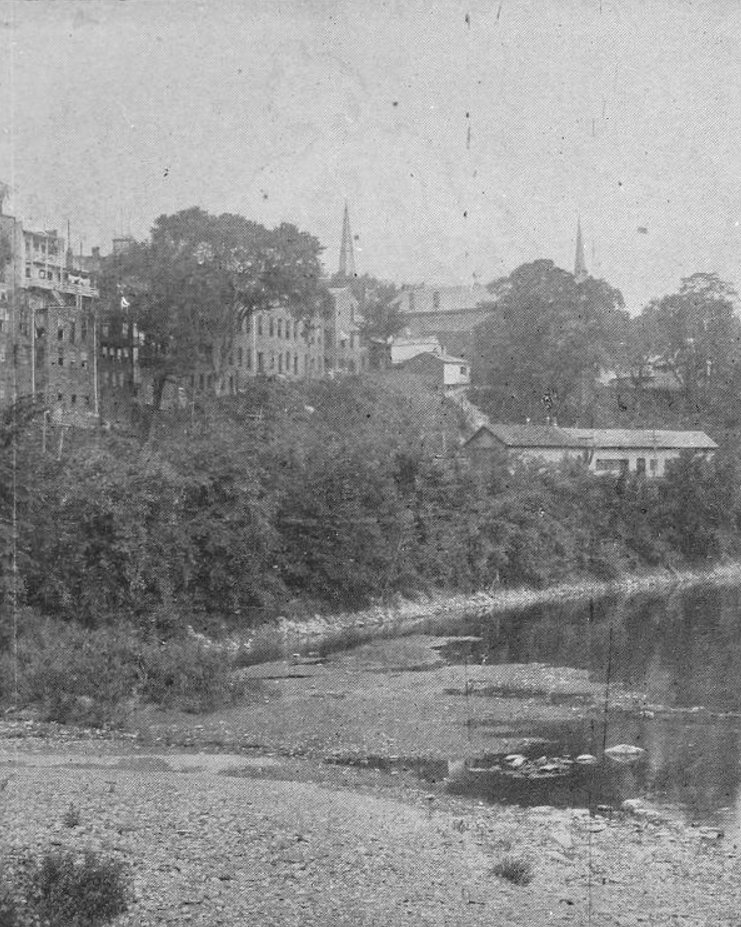

The scene in 2017:

During the first half of the 19th century, a number of alternative medical treatments gained popularity in Europe and the United States. Among these was hydrotherapy, also known as water cure, which involved wraps, baths, and drinking large quantities of water in order to treat a wide range of ailments. The thinking was that water – particularly cold, pure spring water – would flush out impurities in the body, and would restore a person to health. Like most of the other medical treatments of the era, these claims were often dubious, but hydrotherapy was certainly less harmful than many of the often dangerous patent medicines that were peddled turing this time period. It was marketed as a natural alternative to such drugs, and these water cure facilities enjoyed a heyday in the United States around the middle of the 19th century.

One of the earliest and most prominent of these water cure establishments was the Wesselhoeft Water Cure, which was opened here in Brattleboro in 1845 by Dr. Robert Wesselhoeft. A native of Germany, where hydrotherapy had gained popularity in the early 19th century, Wesselhoeft subsequently immigrated to the United States, and earned his doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania in 1841. Several years later he came to Brattleboro, after determining it to be an ideal location with pure water. As he described it, “Fresh springs issue from all the hills. The water is the purest I could find among several hundred springs I have visited and tested, from Virginia to the White Mountains, within two hundred mines of the seacoast.”

In 1844, Dr. Wesselhoeft purchased the buildings at this location, on the northwest corner of Elliot and Church Streets. After some additions and remodeling, the water cure was ready to open the following year, on May 29, 1845. The water cure had only 15 patients at first, but this soon increased to around 150, with men housed in a building on the west side, and women in the east building, which is seen here in the first photo. By the following year the water cure had nearly 400 patients, which was beyond the capacity of the buildings, and many to stay in nearby hotels and boarding houses. The facility was expanded over the next few years, and by 1848 Dr. Wesselhoeft has to hire a second physician, fellow German immigrant Dr. Charles W. Grau, to keep up with the demand.

The book Annals of Brattleboro, 1681-1895 provides a description of a typical patient’s treatment, which was written by Dr. Wesselhoeft:

The patient is waked about four o’clock in the morning, and wrapped in thick woollen blankets almost hermetically; only the face and sometimes the whole head remains free; all other contact of the body with the air being carefully prevented. Soon the vital warmth streams out from the patient, and collects round him, more or less according to his own constitution and the state of the atmosphere. After a while he begins to perspire, and he must continue to perspire till his covering itself becomes wet. During this time his head may be covered with cold compresses and he may drink as much fresh water as he likes. Windows and doors are opened in order to promote the flow of perspiration by the entrance of fresh, vital air. As soon as the attendant observes that there has been perspiration enough, he dips the patient into a cold bath, which is ready in the neighborhood of the bed. As soon as the first shock is over he feels a sense of comfort, and the surface of the water becomes covered with clammy matter, which perspiration has driven out from him. The pores, which have been opened by the process of perspiration, suck up the moisture with avidity, and, according to all observations, this is the moment when the wholesome change of matter takes place, by which the whole system gradually becomes purified. In no case has this sudden change of temperature proved to be injurious.

Such treatments were believed to cure a wide range of illnesses. The 1848 book The Water Cure in America, which was co-authored by Dr. Wesselhoeft and several other physicians, included a number of case studies and testimonials from patients here in Brattleboro. According to these claims, the water cure could treat conditions such as lumbago, hemorrhage from the liver, scrofula, scarlet fever, paralysis, swelling of the knee, lung disease from measles, fever and ague, chilblains, typhus of the lungs, typhoid fever, iodine poisoning, boils, bronchitis, dyspepsia, rheumatism, curvature of the spine, and even smallpox.

The book also promised relief from “Headache, Cold Feet, Costiveness, and slight attacks of Hypochondria and Hysteria, from depression of Spirits.” This group of ailments primarily afflicted patients who were “of the female sex, and of students, who, by their sedentary habits, contract congestion of the blood in the lower abdominal organs.” The cure for this was “cold washings, sitz, and foot-baths, two injections a day of one tumbler of water 72º each, wet bandages on the abdomen and loins, drinking of nothing but water; a light diet, and removal of woollen underdresses.”

A stay at the Wesselhoeft Water Cure cost $10 per week in the summer, and $11 in the winter. This covered all expenses except for laundry, but patients also needed to provide the following items, which could be rented or purchased:

- At least two good large woollen blankets.

- A feather bed, or three comforters.

- A sheet of coarse linen, which can be cut, or at least one piece of inch linen, six qrs. long, and six qrs. wide; also, pieces of linen, and cotton, for bandages.

- Two coarse cotton sheets.

- Six towels.

- One injection instrument.

In addition, Wesselhoeft’s description in The Water Cure in America advised that “Very sick, and helpless patients, for whom the ordinary attendance would not be sufficient, must hire a nurse, or waiter, who can be boarded at $2.50 per week.” Those who did not wish to stay at the establishment could stay at one of the nearby boarding houses for $3.50 to $5.00 per week, plus a $5.00 per week fee as a day guest at the water cure. However, these charges were advertised as being negotiable, with Dr. Wesselhoeft offering reduced rates for poor patients whenever possible.

During its heyday in the 1840s and early 1850s, the Wesselhoeft Water Cure attracted patients from around the country, including a number of prominent figures of the era. Former President Martin Van Buren was a patient here, along with poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, abolitionists Samuel Gridley Howe and Julia Ward Howe, and authors Richard Henry Dana, Francis Parkman and Harriet Beecher Stowe. The latter spent 11 months here in 1846 and 1847, several years before she achieved widespread fame as the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Ironically, the same establishment that catered to so many prominent northern abolitionists was also popular among southerners in the antebellum era, and they comprised about a third of Wesselhoeft’s business.

Dr. Wesselhoeft returned to Germany in 1851, where he died the following year, but his widow Ferdinanda carried on the water cure even after his death. However, by this point it was in decline, and this would only get worse after the start of the Civil War in 1861, when southerners stopped traveling to the north. The first photo was probably taken around this time, and the water cure finally closed in 1871, after having been in business for just 26 years. The building, which had once attracted some of the most prominent Americans of the mid-19th century, was subsequently sold and converted into tenements. It remained here for some time afterward, but it was eventually demolished, and its former location is now the site of the current fire station.