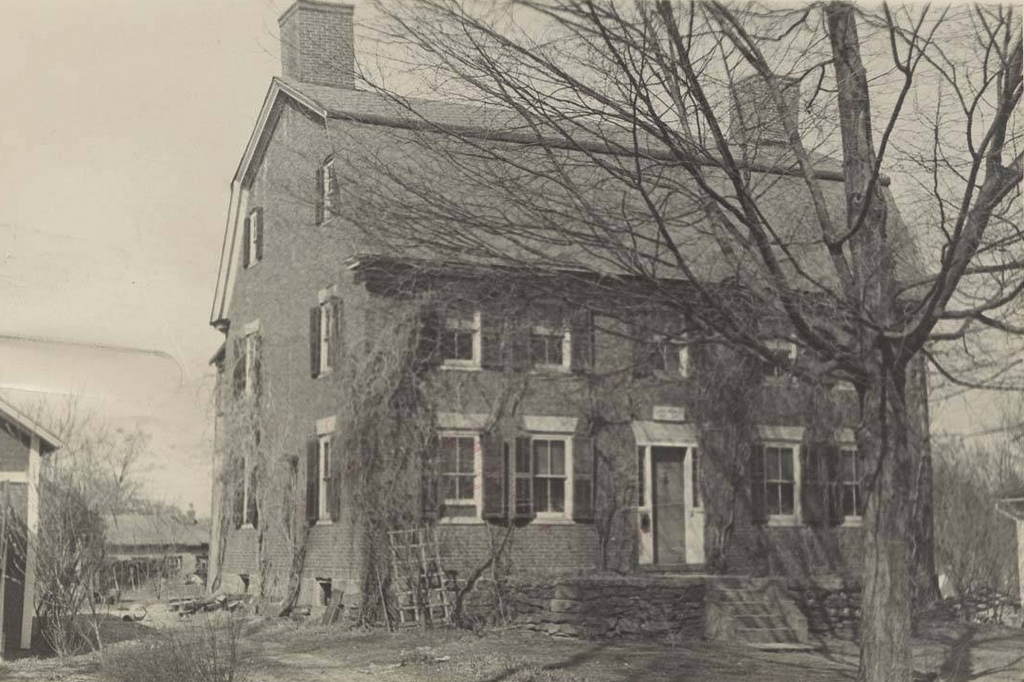

The house at 493 Main Street in Wethersfield, around 1935-1943. Image courtesy of the Connecticut State Library, State Archives, RG 033:28, WPA Records, Architectural Survey.

The house in 2024:

This house is a classic center-chimney colonial New England house, with a design that was found throughout the Connecticut River Valley and beyond during the second half of the 18th century. Distinctive exterior characteristics include a symmetrical front façade with five windows on the second floor and four on the first floor, a large central chimney, and a door on the south side of the house that opens directly into the south parlor. This latter feature is often referred to as a “coffin door,” which according to legend was installed in center-chimney houses to make it easier to move a coffin out of the parlor after a funeral, since the front entryway is small and requires twists and turns to access the front door. The truth behind this legend is uncertain, but having a door to the south parlor undoubtedly makes it easier to move large objects in and out of the house.

The house in these two photos was built in 1765 as the home of Samuel Hanmer Sr. (1741-1813), a local cooper. At the time, Wethersfield was an important seaport, so Hanmer’s barrels were likely used by the town’s merchants who were involved in the West Indies trade. He probably had marriage in mind when he built this house, because two years later he married his wife Sarah Welles (1743-1818). The couple went on to have eight children over the next two decades: Sarah, Abigail, Hulda, Samuel, Elizabeth, Prudence, Nancy, and Joseph.

Although both Samuel and Sarah died in the 1810s, the house would remain in their family until well into the 20th century. The 1855 county map shows the property as belonging to the “Heirs of Samuel Hanmer,” likely referring to their son Samuel Hanmer Jr. (1778-1850), who had died a few years earlier. Then, in 1869 the county atlas identified it as belonging to Charles Hanmer (1839-1884), who was the son of John Hanmer (1801-1881) and grandson of Samuel Hanmer Jr. The 1870 U.S. Census shows Charles living here with his wife Clara (1842-1932) and their young sons Alfred (1867-1953) and Charles (1869-1953). They also had a 14-year old farm laborer named Clarence Deming who was living in their household.

The younger Charles Hanmer was still living here in this house when the top photo was taken around the late 1930s or early 1940s. The photo was part of Depression-era program to document historic 18th and early 19th century buildings across Connecticut, and it was one of the many that were photographed here in Wethersfield. By this point, the house had likely undergone some exterior changes since it was built. The Greek Revival style doorway appears to have been added at some point in the first half of the 19th century, and the 6-over-6 windows may have been installed around the same time, since 12-over-12 ones were more common when this house was built in the mid-18th century.

The top photo was taken when the front door was open, so it provides a glimpse into the front entry hall and the front staircase. Because the center chimney occupies a large footprint within the interior of the house, it does not allow for a large staircase. Instead, the stairs twist around the entry hall on their way up to the second floor.

The 1930 census shows Charles Hanmer living here with his wife Leila (1871-1954), their daughter Charlotte Cowan (1894-1982), and Charlotte’s son William (1925-1977). This made William the seventh generation of his family to live in this house, as he was the 4th great grandson of Samuel Hanmer Sr.

At the time of the 1930 census, Charlotte was married, but was evidently separated from her husband, Jerome Cowan (1897-1972). He was a Broadway actor, and they had married in 1924, around the time that his Broadway career started. However, they were not living together in 1930, and they divorced a year later. Jerome would go on to achieve prominence as a film actor, starring in a number of films from the late 1930s through the early 1960s, including The Maltese Falcon and Miracle on 34th Street. In the meantime, though, Charlotte went on to have a successful career of her own in the insurance industry. She was the first female officer at the Connecticut General Life Insurance Company, and by the time she retired in 1959 she was the company’s assistant comptroller.

Charles, Leila, Charlotte, and William were all still living here in 1940, and all except for William in the 1950 census. Charles and Leila both died in the 1950s, and at some point Charlotte moved to Hartford, where she died in 1982 at the age of 88. She appears to have been the last direct descendant of Samuel Hanmer Sr. to live in this house, ending two centuries of consecutive generations of ownership.

Today, more than 80 years after the top photo was taken, not much has changed here on the exterior of the house. Aside from the 19th century alterations, it retains its historic appearance, and it stands as one of the many well-preserved 18th and early 19th century homes that line Main Street in Wethersfield. It is a contributing property in the Old Wethersfield Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.