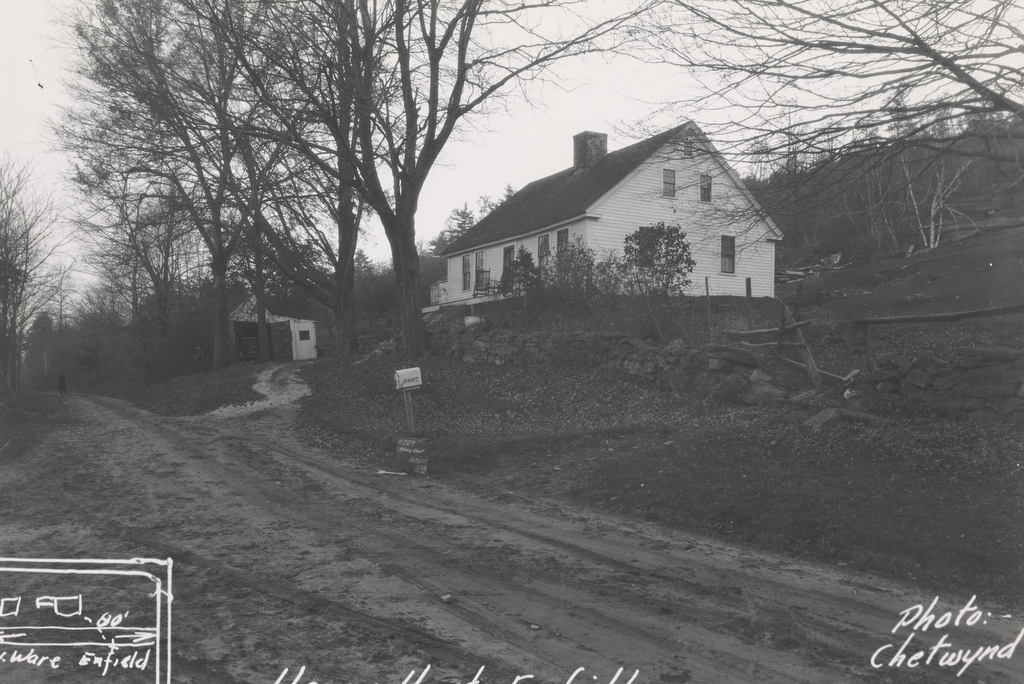

The Martindale Farm in Ware (formerly Enfield), Massachusetts, on April 6, 1946. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan District Water Supply Commission, Quabbin Reservoir, Photographs of Real Estate Takings collection.

The scene in 2024:

This house, located on Webster Road in the town of Enfield, Massachusetts was built around the year 1800 by Jesse Fobes. Jesse moved to Webster Road in 1796 from Bridgewater, MA into a smaller house just north of this property. Once this home was completed, he would move his family to the much larger farm house. When Enfield became an incorporated town in 1816, Jesse would serve as one of its first Selectmen. Ownership of the farm would be passed onto Jesse’s son, Henry Fobes. Much like his father, Henry would also become a Selectmen of the town. Henry would hold onto ownership of the farm until selling it to Joel and William Martindale in 1870 for $8,000. Included in the sale of the farm was a provision that the Martindale’s would have to house and feed Henry until his death. Considering Henry lived another 15 years until dying at the age of 92 in 1885, it seems like Henry got the better end of the deal.

By the 1880s, the farm had a considerable amount of outbuildings. On the 182 acre property were a large carriage shed, garage, hen house, brooder house, three barns, and an assortment of other smaller chicken coops. Joel Martindale would officially call the farm Maple Terrace, in reference to the three terraces that lead up to the front of the house. A sketch of the farm house with its terraces and some outbuildings was even included in the 1879 book History of the Connecticut Valley in Massachusetts. Maple Terrace had become something of a local landmark by this point.

The farm would pass into the hands of Joel’s grandson, Emory Bartlett in 1917. He would drop the Maple Terrace name, and officially incorporate the farm as Martindale Farms Inc. But the glory days of the farm were farm behind at this point. Only a few years later, Emory would sell the farm to Harry Ryther in 1925 as payment for a large debt.

Because of its proximity to the Quabbin Reservoir watershed, the Massachusetts Metropolitan District Water Supply Commission purchased the house and the 182 acres it sat on from Harry Ryther in 1934 for the sum of $11,900. Two Martindale sisters were still living in the farm house when the Water Supply Commission purchased the property.

Martha and Mary Martindale were daughters of Joel Martindale, and both had lived in the house almost their entire lives. This led to debate as to whether or not the home should be torn down. The home appears to be right on the line of the watershed, so some thought the house should stay up and be used as employee housing. Others believed the home was still too close to the reservoir, and should be torn down immediately. An agreement was reached with the Water Supply Commission that allowed the Martindale sisters to live in the home until they either died or moved away. During that time, the home would also be used by Quabbin employees.

Mary Martindale would die in 1952 at the age of 77. Her sister, Martha would decide to move out of the large home into a smaller apartment in Springfield in 1955 so she could be closer to her remaining friends and family. Martha Martindale would be the last private resident to live inside the boundaries of the Quabbin Reservoir land. The home was torn down shortly after, and the landscape allowed to go wild. Building materials from the home were reported as being reused in a future home in the area.

The before photo was taken in 1946, much later than many of the Water Supply Commissions photos of old Quabbin homes. At this point, the reservoir was already fully flooded and the home was now located in the town of Ware, following the disincorporation of Enfield in 1938. Today, the terraces to the home are still clearly visible when you visit the farm. The home’s cellar hole is completely filled in, and much of the yard is overgrown with brambles and vines. The foundations for the outbuildings are easily found out of frame to the right of the photo. Walking down the old driveway leads to the foundations of the barns, as well as some stone walls. The tree to the left of the house in the before photo is almost certainly the same tree on the far left of the current photo. Other old trees can be seen today that would have been very young at the time the home was sold to the Water Supply Commission.

The Martindale Farm is one of the best and most easily accessible spots in Quabbin for history lovers. Located near the end of Webster Road through Gate 53, the old farm is located in a large clearing on the west side of the road. In the summertime, Quabbin rangers will sometimes do history programs at this location and go into greater detail on who the people were that owned this farm.