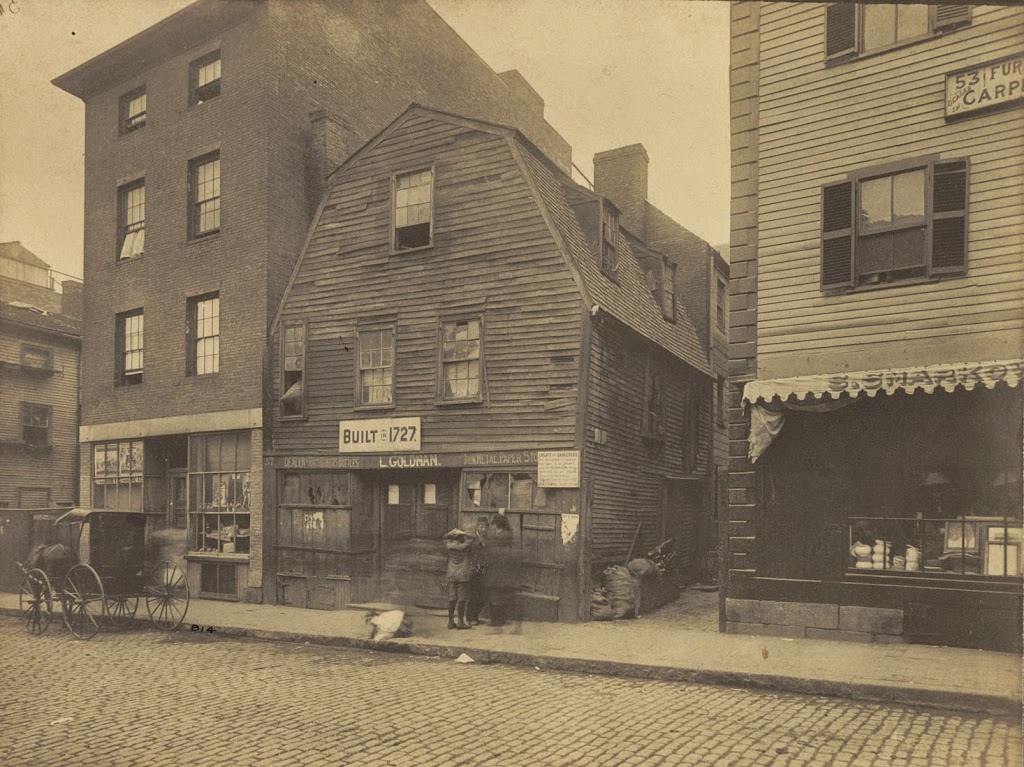

The Thoreau House on Prince Street, near Salem Street, probably in the 1890s. Photo courtesy of Boston Public Library.

The location in 2014:

Although most commonly associated with Concord, some of Henry David Thoreau’s family was from Boston. This house was in his family for several generations, starting with his great-great grandfather David Orrok in 1738. After Thoreau’s grandfather died, ownership of the house was split among the eight children, including Henry David Thoreau’s father John Thoreau, although I don’t know that he or his children ever lived here. In any case, the house, which was built in 1727, remained in the Thoreau family until 1881, and was demolished in 1896, a year before the completion of its present-day replacement, the Paul Revere School.